As someone who has lived in and studies the Middle East I am often asked my opinion on the situation of women in that region. Of course it’s impossible to comment on “women” anywhere, even in Champaign or Urbana, without simplistic overgeneralizations, but discussing the women of the Middle East, a region we appear to be both physically and culturally at war with, is akin to entering a hall of mirrors. We can see many things, but we can never be sure how many illusions contribute to our view.

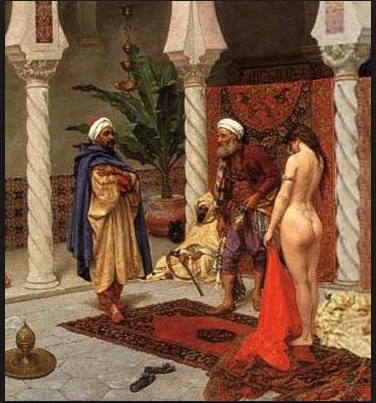

There are many ways current global politics affect how we in the U.S. see the situation of women in the Middle East, and the most familiar pattern is the newly reborn Orientalist trope of victimized women in need of rescue. Fighting to liberate the women of Afghanistan from the oppressive reign of the Taliban was an easy sell after 9/11, and those who argued that the U.S. should have instead pursued an international criminal case against Bin Laden looked downright unchivalrous. The Taliban certainly deserved their sexist reputation, but as an international community we have hardly made defending human rights a consistent plank of foreign policy. In 2001, however, images of women under Taliban control appeared in abundance. They certainly fed the American need to see the invasion in the most positive light, but they also implicitly denigrated local males who had apparently been either complicit in the abuse or incapable of ridding their country of the Taliban scourge. Women under the Taliban did endure horrific restrictions, but looking at the larger context of these depictions of victimization, it’s clear that the women of Afghanistan were exploited not only by the Taliban, but by the conscious and unconscious needs of the U.S. after 9/11.

Morocco, a country touted for its “moderate and progressive Islam,” presents a different form of exploitation of women. In 2004 King Mohamad VI led the reform of the Mudawana, or family law code, an act that won him wild praise in the international press. The reforms left family law under the control of traditional Islamic courts, however they did improve women’s legal situation. Reforms included the new right to initiate divorce, to have a legal identity (as opposed to having to round up a male relative if you wanted to do business at the bank or sign marriage papers), and raising the minimum age for marriage to 18. While they weren’t perfectly conceived or applied, they have helped open up a space for debating the topic of women’s rights and marital happiness in the public sphere.

On another level, unfortunately, the reforms have helped gloss over inconvenient questions of privilege. Women with job opportunities, literacy, and access to legal advice will certainly benefit far more than rural women, who struggle with crushing poverty and inequitable access to school and the courts. Do these women really have more concerns in common with urban women than with their male neighbors? Or would they have been better served by a serious commitment to rural poverty alleviation? Of course, the two are not mutually exclusive, but every time Morocco’s income inequality attracts domestic or international attention, the monarch can respond by pointing to the 2004 Family Law reforms as evidence of his progressive reign. Addressing the issue of women’s rights was a convenient way for the king to win positive marks (and investment and aid) from the U.S. and Europe, and deflect attention from corruption and inequality.

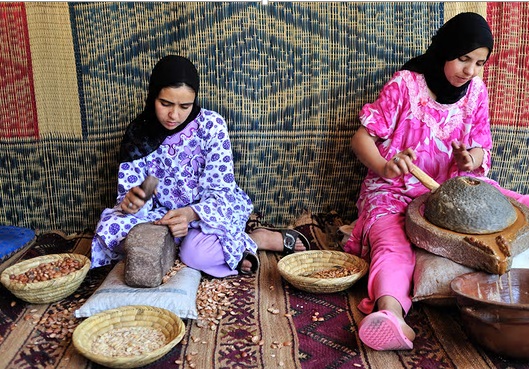

Poor women are not completely neglected in the debates over women’s situation in the Middle East. In Morocco and other areas women’s artisan cooperatives have gained fame for helping many individuals support their families, but, again, the broader context both of the cooperatives and the topic of the cooperatives must be acknowledged.

Rug weaving, argan oil production, and lavender cultivation are just some of the industries that have latched on to the label of the co-op in Morocco. “Cooperative,” however, is an inexact term, and not all cooperatives are equal in allowing local participants control over their industry. In some cases, the new groups contribute to overuse of local resources, degradation of the environment, and the absence of girls from school, all without necessarily contributing to women’s independence. “Cooperative,” in short, has become a marketing term that appeals to many who wish to reframe their consumption of goods as a political, not a personal, act. It is an easy form of solidarity that elides the inequities of producer and consumer. It feels good. And if our enthusiasm is focused on the appeal of helping women achieve independence, from whom are we saving them? Are we unwittingly participating in part of a long tradition of denigrating the unnamed, but clearly deficient local male?

These women’s industries are often also marketed through claims of timeless, female-controlled knowledge of natural remedies. Beauty products, especially for the hair and skin, that promise to reverse the signs of aging are curiously associated with female empowerment. Besides the irony of using anti-aging products to achieve liberation, our idealization of a world far removed from our own ignores the brutal realities of high child mortality and the physical compromises of poor health that are often the lot of many rural communities in the world. It’s an easy escapism that we may occasionally desire from our lives, but it also contributes to a vision of the world that stresses female solidarity while discounting profoundly different circumstances. Consuming responsibly means looking past both the marketing and our own illusions.

While the pitfalls involved in looking at the situation of women in other contexts than our own are aptly illustrated in the examples above, this doesn’t mean that we should abandon the effort. It just means that, especially in the cross-cultural context of the Middle East and the West, there is a great need to be wary of the ways in which women are explicitly and unconsciously exploited for story lines and purposes that are not their own.