“You need some vitamin F.” That’s the teasing advice Claudine gets from her women friends after she complains of not sleeping well.

“Could you live without a man around the house?” Alice Hyatt and her neighbor Bea ponder this question.

Let’s throw back 40 years or so to explore the question: How did American film culture tell the story of women’s liberation?

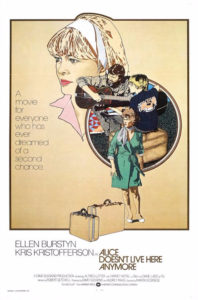

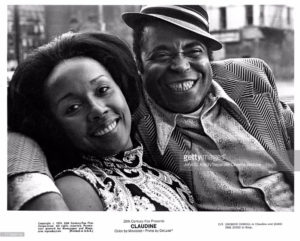

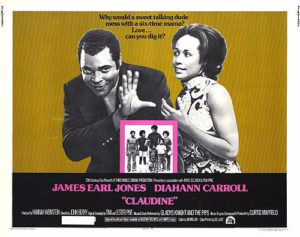

I recommend a double feature: Claudine (Diahann Carroll, James Earl Jones) and Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (Ellen Burstyn, Kris Kristofferson). Both female leads received Oscar nominations for Best Actress. (Ellen Burstyn won.) Both films center around single mothers, their children, lovers, friends, and efforts to make a living. The films hit theaters in 1974, the year the Equal Credit Opportunity Act made it illegal to require single women to have male co-signers in order to apply for credit.

For a midnight chaser, watch filmmaker Lizzie Borden’s 1983 Born in Flames, set in a future America ten years after a peaceful transition to a socialist government, where some women feel compelled to form the Women’s Army.

Claudine was produced by the Third World Cinema Corporation, formed in 1971 by actors Ossie Davis, Rita Morena, James Earl Jones, Diana Sands and producer and political activist Hannah Weinstein. John Berry, who was blacklisted in the McCarthy Era, directs.

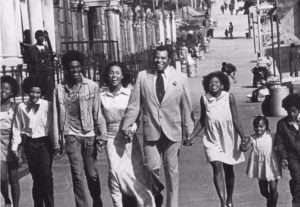

Claudine is rightly billed as a drama and a comedy. Claudine lives in New York City with six children, works off the books as a maid for a wealthy suburban family, and contends with a social worker whose job it is to track and deduct any external source of support from her government assistance, even small household gifts from her boyfriend Rupert (Roop), a garbage collector played by James Earl Jones. The charming Roop has children of his own and has to deal with his wages getting garnished for child support. When Claudine’s oldest son gets involved with the W.E.B. Dubois Community Center, the film’s politics widen further.

The comedy comes in the dialog between Claudine’s friends, her children, and in the delicious romantic interplay of Carroll and Jones. Curtis Mayfield wrote the music and produced the wonderful soundtrack, which features Gladys Knight and the Pips. The film carries viewers swiftly in an out of settings and is a trip back in time. Props and costumes from the 1970s, like the wide ties and portable record players, are fun to see, as are the streets of New York. Claudine flew under my radar until recently. I am happy to have discovered it.

The sitcom Alice may come to mind when you think about Martin Scorsese’s film Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore because the show was a spin-off, but if you haven’t seen the film in decades, or not at all, do not mistake it for the television comedy, and check out the movie. Scorsese’s masterful handiwork is evident in the many panning shots, warm tones, and feel for place and setting. In addition to Burstyn and Kristofferson, the screen fills with now-familiar actors such as Jodie Foster (at age 14), Harvey Keitel and Diane Ladd (nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her portrayal of Flo, foul and funny).

The film triggers nostalgia in the sepia-toned opening shots of a farm like the one in The Wizard of Oz, with Alice Faye singing “You’ll Never Know” from a 1943 film on the soundtrack. Then the young Alice, looking much like Dorothy, sets us laughing with her foul mouth. She wants to grow up to be a singer better than Alice Faye and says anyone who doubts her can “blow it out their ass.” We fast forward 21 years and find saucy Alice married and a mother living a dour life in Socorro, New Mexico. The quest in her adult life is to get back to the confidence and self-determination of her girlhood.

Divided into three acts, the story begins with Alice working hard and failing to please a chronically angry, truck-driving husband. She resorts to weeping into her pillow to elicit physical affection from him. She reveals her true self to her smart, funny 11-year-old son, and they collude for survival. The second act has unexpectedly widowed Alice and her son start west for California but take a break in Tucson to earn cash. Alice finds work as a jazz singer but soon has to flee for safety and makes it to Phoenix, the setting for the third act. Here she works at Mel’s diner and some of the film’s more comic moments find life in the diner’s various characters. Valerie Curtain as Vera adds an absurdist dimension and even slapstick. The enjoyable soundtrack starts with Alice Faye but moves through the Gershwins, Mott the Hoople and Elton John. Like Claudine, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore is great as a period piece but still has relevancy in its situations.

In stark contrast, Born in Flames features music from The Bloods, an all-female punk-funk band, and rockers The Red Krayola. Lizzie Borden’s 1983 underground, feminist film still stands out for its originality and relevance (eerily in the ending), and is enjoying a revival, having been recently restored by Anthology Film Archives in New York City. As a result, it’s easy to find engaging, current interviews with Borden.

Pieced together over many years on a limited budget and using mostly untrained actors, the film feels ragged, raw, radical and real. Florynce (Flo) Kennedy, activist lawyer and founder of the Feminist Party in 1971 that nominated Representative Shirley Chisholm for president, plays a prominent role in the film. Set in NYC “Ten Years After the Social Democratic War of Liberation,” the story surrounds women who retain second-class status and organize rebellion, the government who tracks them, radio DJ’s who promote them, and young women journalists transformed by them. This provocative film is a sure way to stimulate discussion. As Borden says in her February 18, 2016 Flavorwire interview with Alison Nastasi: “The reason I had set it after the first social democratic cultural revolution was that, even after the revolution, there still will be the “woman problem.” Women will still be discriminated against. There still will be white, male privilege. Even after the most idealistic win, what do you do about the “woman question”? (http://flavorwire.com/561757/choice-is-paramount-to-everything-filmmaker-lizzie-borden-on-the-radical-feminism-of-born-in-flames