Second of two parts.

On December 20, the European Commission—the executive arm of the European Union (EU), consisting of one representative from each of the 28 member countries—launched the “nuclear option” of EU politics against Poland: a proposed formal warning that “fundamental values” of democracy were at risk because of actions by the ruling Law and Justice Party government (PiS in its Polish initials). If corrections were not made within three months, it could lead to the deprivation of the country’s EU voting rights—never before attempted—under Article 7 of the basic EU treaty. The immediate trigger for the action was new laws facilitating government control over the Polish judiciary; but the European Parliament vote the previous month initiating the process was also based on moves against the independence of the media and the civil service.

New Polish Prime Minister Mazowiecki (R.) meeting Hungarian PM Orbán in January in Budapest, with backdrop of ceremonial “Hussars.”

In early January, the new Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki—who had taken office several weeks earlier as part of a PiS cabinet shake-up—made his first bilateral visit abroad, to Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Hungary. He was looking for assurances that Orbán’s government would block any final Article 7 vote, which could be foiled by just one dissenting country. But the visit, greeted with great fanfare, including a Hussar band (the Hussars were legendary light cavalry soldiers, prominent in freedom struggles over the centuries in both Hungarian and Polish history and memory), also had strong symbolic importance. Since winning a “supermajority”—one large enough to make constitutional changes on its own—in the 2010 elections, Orbán’s conservative nationalist party, Fidesz, has gained and consolidated complete power in Hungary. Since then, with the help of a massive and virulent anti-immigrant campaign (see my article “‘Anti-Refugeeism without Refugees’ in Eastern Europe” in the November 2016 Public i) and constant propaganda against the EU’s allegedly anti-national, anti-Christian, even “anti-European” bias and policies, he was reelected in 2014, and is almost certain to be elected again this spring for four more years. PiS, elected by a narrower plurality of voters (37%) in late 2015, aspires to match that example of power and control, as well as securing a solid ally within the EU.

There is growing fear, in Brussels and across the Bloc, of what one observer has called an emerging “Authoritarian International.” Such a formation would be anchored in Hungary and Poland, but also potentially extend to Slovakia and Croatia, both sites of increasingly nationalist governments; the Czech Republic, where a Trump-like businessman, Andrej Babis, recently became Prime Minister and the fiercely anti-immigrant Milos Zeman was just reelected President; and even Austria, where the hard-charging conservative 31-year-old Sebastian Kurz took over as Chancellor in December. Orbán’s conception of “illiberal democracy,” with Turkey, Russia, Singapore or even China as models, rather than Germany, France or Scandinavia, has gained credence on the populist Right. He has been working through the Visegrad Group, a regional policy grouping that includes Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, to consolidate and strengthen anti-immigrant, “pro-(Christian) European identity” forces within the EU. But many doubt that the EU machinery, already confronting Brexit and the rise of the extreme Right outside of government (for the time being) in its core member countries, is up to the task of disciplining a determined member-state government, no matter how far it goes against “European values.” (Exhibits A and B are the failure to act effectively against the entry of the far-Right Austrian Jörg Haider into his country’s governing coalition in 2000, and against Orbán since 2010.)

The concerns of the Eurocrats and Western punditry about the rule of law, media independence, democracy and all the rest are valid: in Hungary, over the past seven-plus years, I have seen the deterioration of public culture, cherished institutions, the educational system, and even individual freedom, in the case of, for example, teachers and nurses afraid to speak out or organize. But what they miss is the sense of dislocation and disappointment among many European citizens, not only in “the East,” who feel left behind and without a voice in the neoliberal “democratic consensus” of EU institutions.

Poland was the site of perhaps the most massive and dynamic union movement in history, Solidarnosc (Solidarity), which mobilized 10 million workers, out of a total population of 35 million, against a repressive and exploitative state within a few months in 1980. Jaroslaw Kaczinsky, the powerbroker within PiS, and his late twin brother Lech were both active in the movement; when the (US-made) “shock therapy” program of the 1990s devastated much of rural and working-class Poland, especially in the southern and eastern regions, and splintered the Solidarnosc forces, the brothers were able to reap the benefit by purveying a politics of cultural resentment to those many losers in the transition to capitalism. The Great Recession, though less severe in Poland than elsewhere in the region, only deepened this discontent, with the neoliberal orthodoxy, including labor concessions and government austerity, coming from Brussels and both Western and local elites. Over two million Poles, and hundreds of thousands of Hungarians, especially young college graduates, have left their home and families for better wages—working mostly in service, retail and construction—in Western Europe (an ironic development, given both governments’ hostility to economic migration from Asia or Africa). PiS’s measures against economic insecurity, including substantial child support payments, the bolstering of welfare payments and wages at the bottom, and the rollback of a previous raise in the retirement age, have been popular and strikingly effective. There is thus a surprising amount of union support, for example among steelworkers, for this program (less astounding is its wide support among farmers).

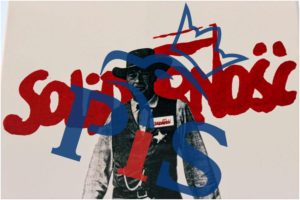

A PiS poster, superimposing the party’s logo onto a famous image from the 1980s’ Solidarity era, featuring Gary Cooper from the film High Noon.

Political scientist and Poland expert David Ost has looked back to the politics of the 1920s and ‘30s for models of the PiS phenomenon, calling it “Left fascism”: ultranationalist and authoritarian, but also attentive to the needs and insecurities of its core, grassroots constituents. Both PiS and Fidesz have successfully channeled legitimate resentment against the EU, and Western European domination of it, against a multi-culturalism and “political correctness” that they say threatens national traditions and identity, and leads to terrorism and never-ending migration crises.

Although the party-level liberal political opposition, in Poland as in Hungary, is discredited, divided and weak, there are signs of hope at the grassroots. Massive protests and a daylong women’s strike in late 2016 by what became known as the “women in black” movement—mourning their loss of rights—managed to turn back an attempt to harden Poland’s abortion laws, already the most restrictive in Europe, into a total ban. Last summer, after more large protests, President Andrzej Duda, though he had been PiS’s candidate, declined to sign into law two of the most damaging measures against the judiciary (although he did sign equivalent laws in December). Counter-demonstrators to the November 11 rightist rally (see part 1) marched under the historic slogan “For Our Freedom and Yours,” showcasing the universalist side of the Polish independence movement. There is, according to Ost, a “small but growing new left in Poland,” exemplified by the new party Razem (Together), which gained 3.6% of the 2015 parliamentary vote despite having been founded only a few months prior.

But in order to really turn around the ship of state, PiS’s opponents will have to go beyond defending liberal causes and the rule of law. They need to recognize those left behind by the imposition of neoliberalism—by liberal elites, ex-Communists and EU institutions from the mid-‘90s on—on Poland. Resistance to PiS’s rightist consolidation must incorporate an economic vision—and a broader sense of inclusion—that reaches beyond the EU status quo.