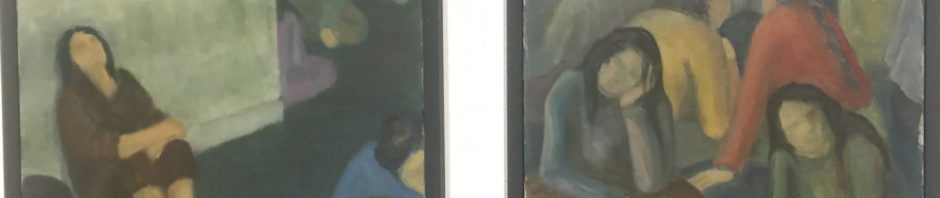

Evin – Ward 4, 1989, by Nasrin Navab, from the exhibition Reckless Law, Shameless Order: An Intimate Experience of Incarceration

One afternoon in April of 2021 Faranak Miraftab called me to ask if I was interested in holding an art workshop with formerly incarcerated artists in continuation of the “IDENSCITY,” a conceptual art space that I had been developing through my praxis as an urbanist and artist looking at identities imposed by the surrounding social order and physical space through time. During our twenty-day road trip around Iran in May, 2019 we had talked about our personal experiences of revolution, war, suppression, mass incarceration, and resistance, and the magic power of art in connecting people to share experiences only expressible in art. My response was simple: “Sure! I’d love to.” Thus was germinated the seed of the exhibition Reckless Law, Shameless Order: An Intimate Experience of Incarceration, which ran at Krannert Art Museum (KAM) on the UIUC campus from February 11 to April 2, 2022.

Faranak, a professor of urban and regional planning at UIUC and an old friend of mine, initiated this project that was ultimately funded by the College of Fine and Applied Arts. She invited Sarah Ross from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Co-director of Arts and Exhibitions of the Prison + Neighborhood Arts Project and Chicago Torture Justice Memorials, to facilitate preliminary workshops. Pablo Mendoza, a formerly incarcerated artist, and Sarah’s students got involved. Outreach to potential artists was through Prison + Neighborhood Arts Project and Chicago Torture Justice Memorials, the Education Justice Project, and First Followers.

The formerly incarcerated artists were invited to take part in three to four art-based facilitated workshops to reflect on their experiences of incarceration, connections, and disconnections. The conversation, were about experiences crossing not only inside/outside physical boundaries of prison but also across national borders and legal systems.

Five artists accepted the invitation. Most of the participants—Pablo Mendoza, Vincent Robinson, Monica Cosby, and Lauren Stumblingbear (Bear)—had spent a big part of their lives incarcerated in Cook County facilities. Imran Muhammad, a young Rohingya refugee, had been granted asylum in the US after seven years of incarceration in Indonesia and on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea. I myself had spent more than three years in the notorious Evin prison in Tehran, Iran.

On September 16, we held our first Zoom meeting, where besides getting to know each other, we talked about possible themes for workshops and artworks for the exhibition. Working with Mirrors, based on one of my previous artworks, was chosen for the in-person workshop on October 2, held in Art at 51, a community art space on the south side of Chicago.

From left to right, artists Pablo, Nasrin, Bear and Vincent are talking about the Mirror Project in the ART@ 51 during the second workshop on October 2. Photo by Monica Cosby

The intimate connections that were made immediately—despite our different backgrounds, languages, genders, and ages—were amazing. We had all experienced the language of power, discrimination, oppression, reckless laws, and shameless orders. Those imprisoned in the US talked about differences in women’s facilities versus men’s, and different behavioral environments, punishment methods, and levels of violence in these two different spaces; gender differences did not prevent them from understanding each other well, nor did the differences in the incarceration systems in Iran, Indonesia, and the US. Imran was a few feet from the water but could not touch it for five years; toddlers accompanying their mothers as well as teenage girls were forced into overcrowded Evin prison’s cells . . . The differences only made everybody more curious to hear each other’s stories.

At the third workshop, on October 22, ideas started to transform themselves into pure art. Sarah interviewed everybody about the heavy feeling of being under observation at all times; and the video art Sound of Surveillance, voiced-over images of surveillance cameras all around the city, took shape and was later completed by her.

In addition, the installation of Illegal Scents, a collection of hanging magazine pages of perfume advertisements, was suggested, and later Sarah and the KAM’s installation team built it.

In late October, I invited Kenneth Norton from First Followers, a formerly incarcerated digital artist, to participate in the exhibition. His work Reflection, alongside other artists’ individual works, attracted many viewers.

Tomb – Joliet 1990s, by Vincent Robinson, from the exhibition

The thirty-eight years between my arrest in May, 1983 and the release of the last member of this group, Bear, in July, 2021, cover an era during which the economic structure and dynamic of power in the world have radically changed. We talked about our experiences and noticed that at the same time that the neoliberal economy was brutally reducing social services, expanding war, and militarizing the police in the outside world, regulations within the prisons were also changing.

The prison population increased sharply, by 500 percent over 40 years, and mass incarceration was used as a class-war technique, especially in Black neighborhoods. With almost 28.5 percent of Black boys experiencing some kind of incarceration in their lifetime, we are facing a social and political problem that affects all of us one by one.

Detail from the collective work Mirror of Time

Step by step, through our conversations, supportive readings and research, and by making art, the idea of the Mirror of Time was formed: a timeline of the last forty years, expressed as a two-sided panel in front of a long horizontal mirror. Our life behind the walls could be seen only indirectly, via the mirror, while in front, reproductions of graffiti images as the voice of the people’s artistic protest against dictatorship, war, and injustice in different parts of the world gave me a new medium to work with. Copies of the artworks of the participant artists were used to create components of this work, which finally got mounted on the wall to make the twenty-foot-long Mirror of Time in the KAM gallery.

Later, Pieces, a video clip by Faranak, was added to this work, and gave more meaning to it. Pieces is a narration of her return to the land from which she was forced to flee 40 years ago, and of our road trip in Iran and intimate conversations about our fragmented lives.

A young visitor on April 2, the last day of the KAM exhibition, in front of Bear’s painting. Photo by Nasrin Navab

During its two months, the exhibition was the venue for several programs. On February 18, a theatrical reading, My Name Is INANA, by Ezzat Goushegir, a playwright from Chicago, was presented with a strong and expressive performance by Maryam Abdi. I had seen the play in Chicago in October, and found it supportive of what we were talking about: time with war, incarceration, immigration, and displacement.

On March 4, a poetry night was held both on Zoom and in person, bringing solidarity and more depth to the exhibition sphere. Two formerly incarcerated poets, Crushion Stubbs and Patrick Pursley, shared their words while Adeyinka Alasade, Matthew Murrey, John Palen, Beau Beausoleil, and Mehri Jafari read to us. This event was in support of the Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here art coalition in defense of the people of Iraq and freedom of the press.

The amazing support of the Urbana-Champaign community, and the diversity and great friends that I have found during my six-month stay in town, encouraged me to move to the area and continue to work with the art community here and in Chicago.The exhibition will travel to Chicago in October.

Nasrin Navab is a painter, teacher, curator, urbanist, and architect. Born in Iran, she has lived her fragmented life in the shadow of war, imprisonment, and immigration, in search of paths toward communal identity and social and spatial justice. She is currently visiting artist at the College of Fine & Applied Arts at UIUC.