The 1912 Lawrence (Massachusetts) textile strike, also known as the Bread and Roses strike

Anarchists, proponents of “anti-authoritarian socialism,” seek to abolish the state and capitalism. Anarchism replaces authoritarian governance and private ownership of resources with federations of self-managed industries and communities in which those affected by decisions participate in making them directly in assemblies, councils, communes, and neighborhoods. Based on voluntary agreements, local workplaces and communities federate with others and coordinate across localities and regions. Workplace organizing has been a major focus for anarchists, and anarchism and labor organizing share a common history in the United States.

Anarchists and state socialists parted ways in the 19th century, when Karl Marx, a leading state socialist, expelled Mikhail Bakunin, a principal advocate of anarchism, from the International Working Men’s Association (IWMA) later known as the “First International.” Marx pushed a program to form labor parties onto IWMA affiliates; Bakunin, along with several of the affiliated sections, resisted making state socialism the governing ideology. Marx, who dominated the General Council of the IWMA in London, then transferred the headquarters to the United States in 1872, where it fell apart a few years later. The International was repressed in most of Europe due to the short-lived existence of the Paris Commune (March 18–May 28, 1871), in which many French members of the International had participated. The Commune frightened the ruling classes across Europe and forced most of the International sections underground. When the Second International was formed in 1889, the state socialists excluded anarchists from joining.

In post–Civil War United States, labor unions were organizing, and both anarchists and state socialists were active in building them, especially in Chicago. In 1884, Albert Parsons, a former Confederate soldier and typesetter, launched a weekly anarchist paper in Chicago, The Alarm. Parsons and his wife, Lucy, relocated to Chicago from their home in Texas, a state that outlawed their interracial marriage and did not approve of their egalitarian beliefs. The Parsons became involved with radical German workingmen, like August Spies, who were trying to build on anarchist ideas in the local unions. Thus was born the International Working Peoples Association (IWPA) and the “Chicago Idea.”

The IWPA was modeled on the First International, and brought together anarchists from Illinois, Pennsylvania, and New York. The Chicago Idea proposed that, instead of trying to foment a political insurrection against capitalism, anarchists should organize within the unions and call for strikes to win not only immediate improvements but also spread to the rest of the working population and bring the downfall of capitalism. Chicago anarchists were impressed by the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, in which a local strike against wage cuts rapidly spread across the country, until most of the railroads had been shut down (much like the 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement spread from one city to another). The Chicago Idea, sometimes credited as a forerunner of anarcho-syndicalism, is the doctrine that unions should take over the means of production and operate them democratically to provide goods and services on the basis of need instead of profit.

The IWPA, along with other unions, anarchists, and socialists, joined together in 1886 to strike for the eight-hour working day. A particularly bitter strike at the McCormick Harvesting Machine Works in Chicago resulted in Chicago police shooting strikers on May 3. A meeting to protest the shootings was held on May 4 at Haymarket Square near the Chicago downtown area. The meeting was peaceful, until an overzealous police captain showed up and demanded everyone disperse. In an act of vengeance for the deaths of strikers, someone threw a dynamite bomb into the police who were threatening the crowd. The police panicked and began shooting wildly, resulting in many of the police being killed by their own. Following the police riot, the leaders of the IWPA were rounded up and put on trial for the police deaths. No evidence was ever produced connecting the IWPA to the bomb thrower, who was never identified. Eight anarchists were found guilty and seven of the eight were sentenced to death by hanging. Samuel Fielden and Michael Schwab’s sentences were commuted to life in prison by Governor Richard James Oglesby; they and Oscar Neebe (the eighth man convicted) were later pardoned by Governor John Peter Altgeld, in 1893. Albert Parsons, August Spies, George Engel, and Adolph Fischer were executed on November 11, 1887, and Louis Lingg took his own life in his cell the evening before.

The next major development came in 1905, when Lucy Parsons and other anarchists, socialists, and industrial unionists founded the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in Chicago. Rebel workers in the US were inspired by developments in France with the founding of the CGT, the General Confederation of Labor, which anarchists helped to organize. Although the IWW never officially adopted “anarcho-syndicalism,” the IWW’s “revolutionary industrial unionism,” in effect, is anarcho-syndicalism. The IWW in many ways anticipated the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and the strike tactics the CIO used to gain a foothold in industry. In fact, the IWW conducted the first sit-down strikes in the auto industry, in 1933. Anarchists were active in many IWW organizing drives in the textile, mining, and lumber industries, as well as among farm workers. The IWW always refused to organize racially segregated unions, and included all ethnic groups and genders, even in the southern states. Sometimes this meant the IWW fought the local KKK.

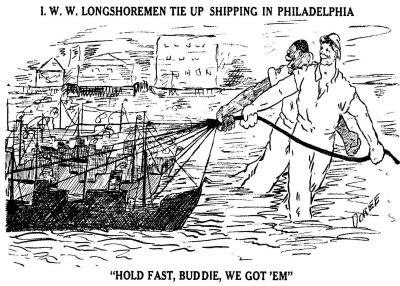

Cartoon celebrating the IWW’s Philadelphia dockers’ strike in 1913]

Anarchism lost most of its influence with the decline of the IWW and anarcho-syndicalist unions in other countries. The Woodrow Wilson administration falsely accused the IWW of aiding the German government in World War I and jailed many organizers. The rise of communism, fascism and welfare-state capitalism also all took their toll. Labor unions became government-certified institutions, heavily dependent on the goodwill of the employers. Anarchists had warned workers that no matter how friendly labor laws might appear at first, their main goal was to control the unions and strikes. This became obvious in the US in 1947, when the previously labor-friendly Wagner Act was replaced by the Taft-Hartley Act, which banned sympathy strikes and demanded all union officers be loyal to the government. The IWW and other radical unions refused to sign onto Taft-Hartley, which left them vulnerable to raids by the conservative pro-capitalist unions. The IWW lost most of its remaining organized shops and membership declined significantly post-World War II, with a few thousand members today. Traditional labor unions in the United States eventually shared a similar fate, with organized labor peaking at 35 percent of all workers in 1954, falling to 20.1 percent in 1983, and further to 10.3 percent in 2019.

Traditional labor unions today engage in collective bargaining and representing members in management disputes with minimal rank-and-file input. Anarcho-syndicalism follows a different path. Direct action, such as “striking on the job” by work slowdowns or other methods, makes more sense than starving on a picket line. We may even see a return to sit-down strikes and workplace occupations, which occurred in Argentina a few years ago. Individual workers, isolated from others, need organization. Rather than go through the National Labor Relations Boards and fight with union-busting attorneys, the IWW now advocates “Solidarity Unionism,” on-the-job actions, sit-down strikes, and wildcat walkouts. Tactics such as a general strike in which all industries are shut down to topple a dictator or force general improvements in conditions have proved effective in democratic struggles in Egypt, Chile, India, and Myanmar.

Jeff Stein is a former organizer for the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and a past member of the IWW General Executive Board. Currently he writes articles for The Anarcho-Syndicalist Review and is a member of the Sam and Esther Dolgoff Institute.