How do you build a solidarity-oriented union? Our Graduate Employees Organization has found that looking beyond the campus and using our voice, funds, and organizing skills to help community causes has made us one of the strongest locals in east-central Illinois.

How do you build a solidarity-oriented union? Our Graduate Employees Organization has found that looking beyond the campus and using our voice, funds, and organizing skills to help community causes has made us one of the strongest locals in east-central Illinois.

GEO (Teachers Local 6300) won a November 2009 strike at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign to protect our tuition waivers. Our success depended on solidarity from campus locals like the Service Employees, AFSCME, and University Professors, as well as Teamsters and other unions that came to campus for deliveries and construction projects. Undergraduates and community members honored and walked our picket lines.

As we negotiated over the same issue again this fall, we planned ahead for another strike—which we averted by prevailing on tuition waivers. As we planned, we counted on support from all kinds of community organizations—groups we’ve come to depend on through our solidarity work. GEO has helped bridge the divide between campus and community that often develops in university towns.

GIVING GENEROUSLY

GEO had a defining moment in 2007, when campus building and food service workers were on the verge of a strike. GEO stewards proposed we make a no-strings-attached donation of over $100,000—the entirety of our strike fund. After discussion, members voted yes overwhelmingly—it was easy to see how a successful strike would directly help us.

Though ultimately SEIU avoided a strike and didn’t need our funds, this moment organized me, a newly active member, to see my union as more than a means to my own contractual gains. The union was a way to engage with struggles for social justice led by other groups in our community.

Shortly after, we created a solidarity line of $10,000 per year in our budget. Any GEO member or community organization could submit a request, which would be voted on by our coordinating committee.

We supported campaigns that helped our community and promoted human rights and workers’ rights, like an after-school program in local public housing; a food co-op’s effort to provide healthy food for low-income people; and the campus coalition that got Coca-Cola out of vending machines because of the company’s record of attacking workers’ rights abroad.

JOINING LOCAL STRUGGLES

But GEO’s solidarity work soon went beyond funding. Members formed a Critical Action and Research Caucus where we discussed historical and current movements for environmental justice, against racism, and against the vast increase in incarceration and expansion of prisons. Our local community had seen a lot of organizing on these subjects.

Then we created a Solidarity Committee and started to attend meetings of community organizations, Jobs with Justice, and the county central labor council.

Members of the Solidarity Committee work exclusively on building relationships in our communities. This means that even when many GEO members are busy with a work action of our own, others stay dedicated to long-term community campaigns.

We joined residents calling for clean-up of toxics in an African-American neighborhood, which led to success after a lawsuit. We worked with Champaign-Urbana Citizens for Peace and Justice, a community organization that fights racial inequalities, especially in the criminal justice system. We requested Freedom of Information Act releases of arrest records and participated in citizen court watches in cases that CUCPJ suspected were motivated by racism.

After a Champaign police officer shot and killed Kiwane Carrington, an unarmed 15-year-old, we developed, with CUCPJ, a brief asking the Department of Justice to investigate racially discriminatory policing. We found that skills particular to our members—research and writing—were useful in these battles.

REDEFINING ‘A LABOR ISSUE’

Through our work with CUCPJ, GEO members came to see criminal justice as a labor concern. In Champaign County, African Americans are 12 percent of the population but more than 54 percent of incarcerated people. Incarceration removes 2.2 million people from the workforce nationally, and a disproportionate number are people of color.

After release from prison, the continued stigma makes it hard to re-enter the workforce, and young people of color already have less access to job training. These inequalities severely limit access to good jobs.

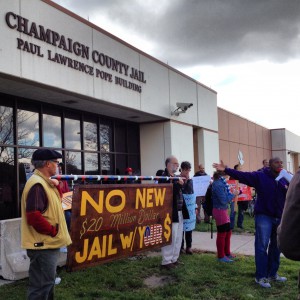

When the Champaign County Board considered spending $20 million to expand the local jail, GEO members worked with CUCPJ to oppose it. The jail was not even full, and we knew from our research that expansions create a motivation to fill the jails up—leading to even more incarceration.

We turned out big crowds of campus workers and students, filling the room at County Board meetings. We helped develop and carry out a public survey and petition, arrange community forums, and research alternatives to incarceration.

Most GEO members involved with CUCPJ have done so explicitly as representatives of the union, so CUCPJ sees us as an organization that works with them, not just a few individuals helping out.

In the past year, our Solidarity Committee has also worked against the federal “Secure Communities” program that detains immigrants for deportation and assisted an organizing drive among factory workers.

TAKING ON A FELLOW UNION

GEO recently joined a human rights campaign to close the “supermax” prison in Tamms, Illinois, whose practices of prolonged solitary confinement and sensory deprivation are defined as torture by the UN.

As far as we know, we and our sister union at the University of Illinois-Chicago are the first unions to oppose the prison. Our resolution is a challenge to the leaders of AFSCME, which represents the guards at Tamms.

Members of GEO had to think seriously before breaking ranks with another union. Ultimately we felt that supporting working people shouldn’t mean we also support the ill effects of their jobs. Labor can support tobacco workers without falling in with the cigarette companies.

Solidarity doesn’t just mean “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours.” It means recognizing how our struggles are connected. We support the closure of Tamms because it violates the human rights of prisoners and guards. Nobody should have to work in an institution of torture.

Solidarity means that we push for fellow workers to have good jobs that contribute to the well-being of our communities, jobs that don’t exploit and dehumanize us. This is the kind of solidarity we want to see grow in the labor movement.

Anna Kurhajec is a Solidarity Committee member in the Graduate Employees Organization.

This article originally appeared at Labor Notes.