India Watcher earned a Ph.D. at UIUC

In a major upset, the two-year old Aam Aadmi Party (AAP, Common Man’s Party) won the elections to Delhi’s state legislature on February 10, 2015, winning 67 seats out of 70.

AAP leader Arvind Kejriwal held a series of dialogues with Delhi constituents during the run-up to the February, 2015 elections.

For weeks before, the national media obsessed over whether the rightwing Hindu revivalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP, Indian People’s Party), of Prime Minister Narendra Modi would continue its run of three straight state election wins after winning the 2014 national election that brought Modi to power. Or, could the AAP leader, Arvind Kejriwal, snatch political victory from the mighty BJP electoral machine that was clearly outspending its opponents in an electoral blitzkrieg? Modi himself addressed several rallies where he never failed to disparage Kejriwal. The results took everybody, even the most ardent AAP supporters, by surprise. Both AAP and BJP had been predicting a majority for their party, but nobody imagined that it would be a vote tsunami for the political underdog.

To understand the reasons for AAP’s victory, and its significance, it is necessary to look at how the AAP was formed. The AAP was set up by activists who participated in the India Against Corruption (IAC) campaign started by Anna Hazare, a social activist from the western state of Maharashtra. The IAC campaign began in 2011 in the backdrop of the Arab Spring, and numerous high-profile scandals in the ruling Congress government. The campaign had a clear goal: pass a Jan Lokpal Bill (Citizen’s Ombudsman Bill) in Parliament to set up an independent and empowered Jan Lokpal (Citizen’s Ombudsman) at the national level to investigate corruption in the government. The fight between civil society and the government continued for two years and a watered-down version of the bill was finally passed in 2013.

Already by mid-2012, the anti-corruption movement had started to fizzle out. In November 2012, Kejriwal and a few others formally split from the movement and formed the Aam Aadmi Party, while Anna Hazare continued down the road of protests and social activism. The founders of the AAP said they wanted to change the way politics was done in the country, using the Gandhian principle of swaraj, self-rule, to encourage “self-governance, community building and decentralization.”

In its first race, AAP came in second in December 2013 in Delhi winning 28 out of 70 seats . The BJP was the single largest party, but did not win a majority and declined to form a minority government. After seeking a referendum from the people of Delhi, the AAP formed a minority government with “not-unconditional” support from the Congress. But Kejriwal resigned after just 49 days when both the BJP and Congress blocked a Delhi ombudsman bill citing procedural lapses.

The AAP’s initials are Hindi for the polite form of “you,” so combined with the simple broom, the logo here may be read as “your party sweeps away corruption”

The AAP ran in the May 2014 national elections, but fared extremely poorly. Of the 434 candidates fielded across India, only four won in the Punjab while all seven parliamentary seats in Delhi were lost. AAP had to face the reality of a disappointed electorate that was angry at not having been consulted before the resignation. The voters felt let down by a party that had been championing participatory democracy.

Though the Indian polity was set up as a democracy, in practical everyday terms, it largely functioned as a feudal system. Politicians and bureaucrats conducted themselves like feudal lords who doled out or withheld the largesse that was really the taxpayer’s money.

The centrist Congress party has occasionally eschewed its sense of entitlement and supported pro-people’s policies: Right to Information, Right to Work, Recognition of Forest Rights, Right to Education, Right to Food, and Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement. But problems in implementation, plus continued corruption, pushed the tide against Congress.

After ten years in the opposition, the Modi-led BJP won a majority in the 2014 national elections. Modi had risen up the ranks of the Hindu fundamentalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS, National Volunteer Organization). But in Delhi last month, the BJP was humiliated with a miserable three seats, and the Congress failed to win any.

In retrospect, the AAP did a lot of things right. Kejriwal apologized profusely to the people of Delhi for his resignation, which voters appreciated since honesty and humility were unknown among Indian politicians. Forty thousand volunteers worked the grassroots, going door-to-door, and organizing public meetings with Kejriwal. Kejriwal himself focused on basic issues — water, electricity and women’s safety — that resonated with the people. By stalling on the election date, the BJP inadvertently gave AAP time to get its act together.

Waving brooms, AAP supporters celebrate victory in Delhi elections, February, 2015

As a senior BJP member blogged, “the failure of the BJP consists of not being able to split the non-BJP votes. ” Between December 2013 and February 2015, the BJP lost just one percent of its one-third vote share, but the opposition vote united behind the AAP, which went from 30 percent to over 54 percent .

The BJP’s election campaign was largely negative. Modi and other BJP leaders targeted Kejriwal, mocking him repeatedly as a “deserter” and “left-wing radical.” Meanwhile, the still-new national BJP government was not exactly covering itself in honor. Day after day, the press reported a new, reactionary plan or statement by the Hindu right-wing radicals who claimed to turn India into a Hindu country. They issued threats against conversions from Hinduism to Islam or to Christianity . They made claims about Muslim men deliberately making Hindu women fall in love with them for the ulterior motive of converting them to Islam (termed “love jihad”). They exhorted Hindu women to have four children apiece. They attacked movies such as Aamir Khan’s PK that showed religious leaders with mass followings as conmen. In Delhi, which was under central rule before the elections, the situation escalated beyond religious threats with a Hindu-Muslim communal riot, and five attacks on Christian churches.

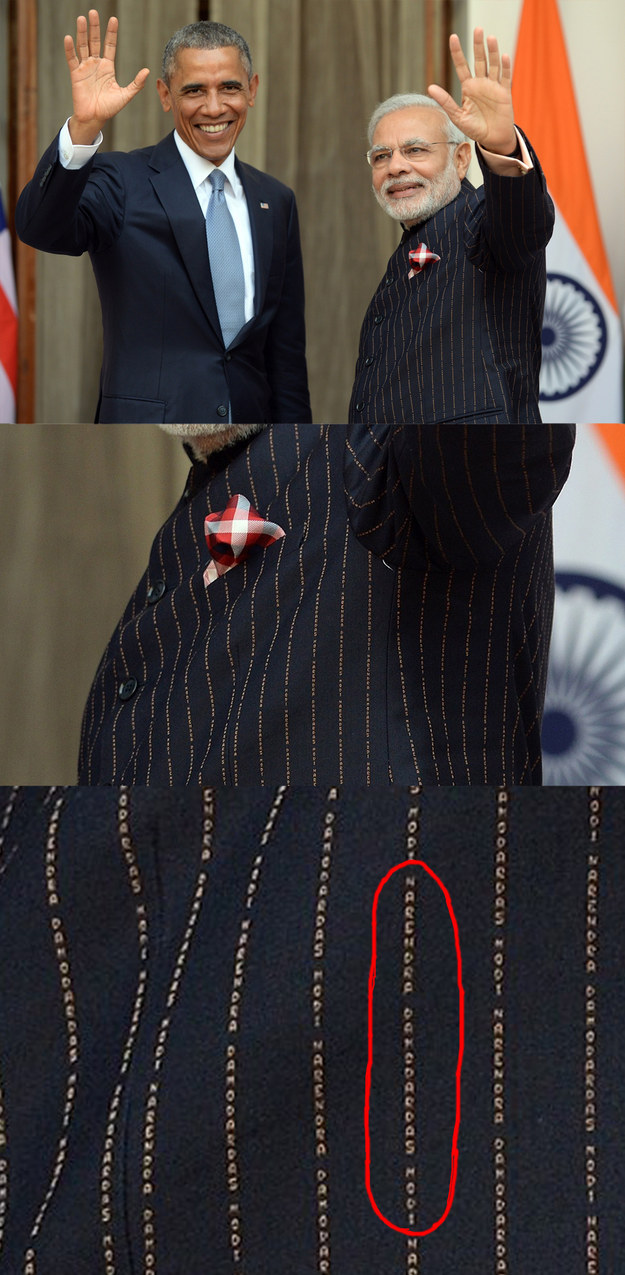

Meanwhile, Modi remained silent about the growing religious intolerance . Instead, the central government systematically packed governmental and semi-autonomous bodies with right wing sympathizers. Modi and his right-hand man, Amit Shah, tightly controlled electoral strategy and machinery . Voices of dissent were gradually being suppressed, especially those of some writers and artists . The disconnect with the common citizen was completed when national news showed Modi wearing a million-rupee (about USD 16,000) suit embroidered with his name in gold when meeting President Obama for tea during his January, 2015 visit.

Prime Minister Modi wore a million-rupee suit to tea with President Obama with his name embroidered in gold all over it

Arguably, Indians are not against change, but the vast majority is wary of precipitous, violent change — either reactionary or revolutionary. They prefer a peaceful route to change, respecting the Constitution and established institutions (note to the revolutionary), while also respecting the beliefs and aspirations of all groups and interests (note to the reactionary). Experience with self-styled “feudal” lords and their misuse of power means any display of high-handedness is distrusted. Hence, the acute contrast between Modi, who spoke of all he alone would do for them, and Kejriwal, who talked about involving the citizenry in running Delhi.

During the India Against Corruption movement, the pro-people perspectives of social activists resulted in citizens beginning to feel it was their right to actually hold their representatives accountable for their actions, behavior, and financial excesses. Even so, the idea of questioning the system was still new. Kejriwal’s confrontational style first as candidate, then as short-lived Delhi chief minister, both elated and alarmed the public. He even questioned the corruption of several high-profile politicians and businessmen, including the son-in-law of Congress President Sonia Gandhi. In his second attempt, Kejriwal toned down the rhetoric and focused more on specific initiatives. He was able to make the emotional connect and the people began to engage in more give-and-take with him.

Only after the crushing Delhi defeat did Modi first speak out against religious intolerance, saying that he stood by the Constitution . Hopefully, he understands the essentially middle-of- the-road nature of Indian society and culture. Yes, a hardcore 30 percent will continue to support the BJP regardless. But perhaps 70 percent of the populace prefers a different kind of politics. A politics that focuses on harmony among communities. A government that focuses on doing things in the people’s interest, not just the party’s interest. A respect for democratic rights – India is, after all, the world’s largest democracy — including accommodating difference and dissent. The nation’s feudal core continues to slowly but definitely change to a more democratic one.

The success of any party also depends on how democratic it is. This has been the bane of almost all Indian parties. Congress paid the price for excessive slavishness to one family (the Gandhis). The BJP paid the price of top duo’s high-handed, arbitrary conduct in the run-up to the Delhi elections. And the intermittent rumblings within the AAP against one-person rule must be resolved democratically if it is to maintain diverse, creative strategies.