The US has opened up talks with Cuba and reestablished formal diplomatic relations so that the two countries’ “interest sections” are now embassies. Could this be a full normalization of relations, or is it just a new US offensive for regime change? Our answer is: Both.

We are scholar-activists who have been to Cuba on many occasions and support the goals of the Cuban Revolution. Opening the possibility of people-to-people contact, better conditions for trade, and better government exchanges is a welcome process for peace and stability in the region. On the other hand, basic US policy has not changed. The illegal blockade continues. The illegal occupation of Guantanamo continues. And the US government objective of regime change holds firm.

The US blockade, or embargo, has been in place since 1960. The US government has reinforced it several times since then. It keeps Cuba from doing business with US entities or with anyone who wants to do business with the US. It isolates Cuba from the world’s banking networks, from shipping, from buying and selling. As a result everything costs more on the island, or is not available at all.

A second event that has put Cuba in deep crisis is the end of its preferential trade with the Soviet Union. The capitalist restoration that tore the USSR apart led Russia to immediately end this trade agreement. The Cuban economy shrank by one-third in three years. The Cubans called this a “Special Period in Time of Peace,” and there are aspects that continue to today. The third major challenge is the constant state of war facing Cuba, based on a history of US-sponsored military interventions and provocations and forcing Cuba to use a huge amount of its resources for the military.

People in the US need to learn more about Cuba, not from the bias of anti-Cuban propaganda, but in face-to-face talk with Cubans themselves. Likewise, Cubans need to learn about the US from all of us. We had this opportunity in CU just last month.

This October, Marta Terry González was a Miller Visiting Professor at the University of Illinois, giving talks and meeting people, thanks to support from eight units on campus and the organizing work of Kate Williams. Marta has been a leading librarian since the Cuban Revolution took power in 1959. She has led Cuban libraries and developed the library profession in Cuba and represented Cuba in international library discussions and debates for over 50 years. At this very moment of an apparent opening of a new stage of US-Cuba relations it was very helpful to have such a visit.

The initial stimulus for organizing this visit was the publication of a biographical study of Marta: Roots and Flowers: The Life and Work of the Afro-Cuban Librarian Marta Terry González by the two of us (Library Juice Press, 2015).

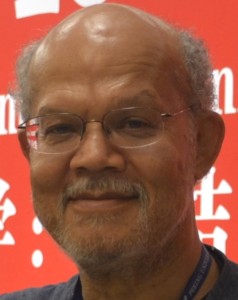

Although in her 80s, Marta spoke on campus every day and also one day in Chicago. Her main MillerComm talk took the form of a dialogue with Abdul Alkalimat. She gave a historical review of the different leadership roles she has had. She was head librarian at the Economic Planning Board (JUCEPLAN) for six years, with Che Guevara among the leadership. For 20 years she directed the library at Casa de las Américas under the leadership of Haydée Santamaria, one of the handful of women who fought with Fidel in the mountains before taking power. For 10 years she directed the José Martí National Library of Cuba, working with Minister of Culture Armando Hart. She has also worked at or established several other libraries. She helped expand the internationally acclaimed annual Cuban book fair.

Marta helped to clarify how Cuba is using libraries to build democracy. When the revolution came to power, as they put it in Cuba, overthrowing the US puppet and dictator-president Fulgencio Batista, one million people on the island could not read. There was barely one public library. A slogan emerged, “Don’t believe, Read!,” and to make that possible, the Cuban revolution organized a literacy campaign that became world famous. More than 100,000 teenage literacy teachers went off into all regions of the country to teach people how to read. As a result literacy in Cuba went from 70% (1953) to 96% (1964). The “Battle for the Sixth Grade” followed, and so on. School enrollment went from 56% (1953) to 100% (1986). Marta has a personal tie to this reading culture, as her nephew Pelayo Terry is editor of the daily national newspaper Granma. Put another way, as she said, “The revolution is just people doing things.” In other words, this has meant staying active and on point towards, for instance, free health care provision and free education through the PhD. It has meant building up their country to not be an impoverished neocolony of the United States governed from Washington and New York.

In 1959, when the revolution took power, many of the middle-class elites left the country thinking that they would be returning in a matter of months. They left their belongings including their books. Marta and her long time classmate Olinta Arioso led in sorting through the books and setting up the first school libraries. Later, as head of the National Library, Marta was responsible for building up the entire Cuban public library system. She stabilized this process by helping to form the Cuban professional association for librarians, ASCUBI. Libraries are essential for a democratic society so that the broad population has access to information required for informed decision making.

She led ASCUBI to join the International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA) to learn from and to share with other librarians. As IFLA Vice-President, she was able to arrange for Cuba to host IFLA’s 1994 meeting. She was eventually named an IFLA Honorary Fellow, the first from the Global South. But also at IFLA Marta faced down an attack on Cuba that (it later came out) was funded and fomented by the US State Department. She was engaged in tense ideological and political battles even after the American Library Association sent a delegation, including several librarians from Illinois, to Cuba to investigate. They found small book collections in the living rooms of Cuban dissidents, often funded and supplied by the US government, claiming to be better than the island’s actual libraries. All of this while the US-enforced blockade prevented official Cuban libraries from buying books and subscribing to US publications.

One of the purposes of Marta Terry’s visit was to begin discussing possible connections between US libraries and Cuban libraries, including between the University of Illinois and the University of Havana. Marta was a lead person in building up the library studies program at the University and has been an adjunct faculty since the 1960s. As a result of her trip, faculty and graduate students interested in Cuban research and teaching are planning to begin meeting on a regular basis.

Cuba offered to send health workers to volunteer after the Katrina crisis but the US government refused. Cuba graduates low income students from the US from their international medical school with free tuition; many of them are now practicing in low income inner city and rural communities. More doctors from Cuba have volunteered to help fight Ebola in West Africa than any other country. Maybe the US can learn something from Cuba.

By Abdul Alkalimat and Kate Williams

Abdul Alkalimat is professor emeritus of African American Studies and Library and Information Science, retired from the University of Illinois. Kate Williams is an associate professor in the Graduate School of Library and Information Science at the U of I.