By David Prochaska

President Barack Obama visited Havana March 2016. Perhaps even more important, the Rolling Stones played a free concert right after. Commercial airline flights to Cuba are likely to begin in October. Even as the US moves to normalize relations with Cuba, however, and more and more Americans visit the island, Cuba elicits strong, divergent reactions.

Cuba supporters point to universal, free healthcare; low infant mortality and a high literacy rate; universal free education kindergarten through university; a high degree of economic equality; a strong social safety net of services and subsidies; and few, if any, overt signs of oppression.

Cuba critics emphasize growing income equality, especially since the so-called “Special Period,” instituted in 1991 when the Soviet Union collapsed and eliminated all aid; bloated state bureaucracies and inefficient state enterprises; a dual currency system that is unworkable in the long run; both a black market and a gray market in goods and services fueled by corruption; fewer human rights abuses than earlier but still few civil liberties; and ongoing structural problems of race and racism, sexism and machismo.

What accounts for these striking differences? Short version: “It’s the Revolution (1959- present), duh.”

For, Cuba is and is not like other Caribbean, and South American, countries.

The original inhabitants, chiefly the Tainos, were completely wiped out within 30 years of conquest, whereas many more indigenous peoples survived, relatively speaking, in South America. At the height of the Spanish Empire, Havana became the chief transshipment center of the galleon trade between the Philippines and Spain. Trade, especially in silver, was the motor that drove the Spanish economy, and provided a huge economic windfall that made Spain the world’s leading power in the 16th-17th centuries.

Cuba is synonymous with tobacco – Cuban cigars – and sugar — notably in the form of rum. Tobacco was introduced earlier, and hand-rolled Cuban cigars are considered by many the world’s best. But sugar has been Cuba’s dominant crop for 200 years. In the 19th century, it was the world’s largest sugar producer. The first railroad in Cuba – the fifth earliest in the world, and 11 years earlier than Spain — was built in 1837 primarily to transport sugar cane. Growing sugarcane was only possible by importing African slaves to work the plantations. Peninsulares, whites from Spain, built up extensive latifundia and became wealthy “sugar barons.” Not until 1886 was slavery eliminated. Work in the cane fields was seasonal. During the growing season, there was relatively little to do, but the harvest required intensive labor. After the 1959 Revolution, the government endeavored to employ workers year-round in order to reduce income inequality, but this economic ideal is like squaring the circle given the seasonal nature of working sugar.

Today, estimates of Afro-Cubans vary wildly, but most studies divide the population into one-third white, one-third black, and one-third mixed race, or mulatto. While economically poorer and predominantly rural, it is generally conceded that amidst changing regime policies, Blacks in Cuba experience much less racism than do those in the US. Slavery is horrific anywhere, although historians have long contrasted the relatively less harsh slave regimes and generally better race relations in South America with the US, especially in the South. To the degree this is so, then the contrast begins just 90 miles off the coast.

The wars of South American independence from Spain 1810-1821 did not reach Cuba. Instead, profits from sugar and fear of slave uprisings kept Cuba Spanish. Possible repeats of a 18th c slave rebellion on a Santo Domingue sugar estate, depicted in Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s cinematic masterpiece, The Last Supper (1976), terrified sugar barons an island away. Instead, Spanish soldiers defeated elsewhere fled to Cuba where they contributed to the “authoritarianism, rigidity, and racism already prevalent” there (p. 3). Shortly after in 1823, the US promulgated the Monroe Doctrine that decreed Latin America off limits to other colonial powers, and the Caribbean ”an American lake.”

Only later in 1868 did Cuba begin a 10-year war of independence that in the end took 90 years of on and off again fighting before coming to fruition in the 1959 Revolution. At first, the Cubans rose up against Spain, and later against US economic and political dominance. Neither nationalist leader José Martí in the 1870s (d 1895), nor the so-called 1898 Spanish-American war, nor the 1930s short-lived revolutionary takeover, lasting only four months, achieve Cuban independence.

Writer and revolutionary Martí during his stay in the US, decried what he called the “metallificacion del hombre,” the “metalification” of a people and weakening of moral values that he witnessed during an age of industrialization and increasing social inequality.

Chief among these events that American schoolchildren learn about is the Spanish-American War, which is known in Cuba, significantly, as the Cuban War of Independence. This is a misnomer, however, because the war was waged not simply between Spanish and Americans but against Cubans, and later against Filipinos. In Cuba, the US fought against Spain but also against the Cubans in effect to deny them the independence they had already won. Thus, the war marked the creation of an American Empire on the ashes of the Spanish Empire, one that comprised the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico, in addition to temporary control over Cuba.

Cuba a De Facto American Colony

Already by the mid to late 19th century, however, the US dominated the Cuban economy, including fully 80 percent of all investment in sugar.

Cuban sugar barons first built opulent “social clubs” in Havana’s Miramar neighborhood along the water where they congregated with their own kind. Soon, however, they were constructing mansions on a palatial scale. Virtually all these elite families fled to Florida immediately after the Revolution. Today, books and YouTube videos reek of elite nostalgia for pre-Revolutionary Cuba. It’s an ideal society idealized. There are no poor people, virtually no people of color, everyone is aristocratic and upper class, there is no dirt. Those who worked, those who literally slaved, to make this lifestyle possible are airbrushed out of the picture. It is as if Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, Camilo Cienfuegos, women, and all the others literally came out of nowhere, crashed the party, broke things up, tore things down, stole their property, and forced them to fly to Miami.

After 1898, the US also became the final arbiter of Cuban politics. If Cubans went along with US interests, fine. If not, the US intervened directly. The US forced the Cubans to add this policy to their constitution in the form of the 1903 Platt Amendment. While it was in force between 1903 and 1934, US troops occupied Cuba three times.

In 1933 FDR appointed Sumner Welles ambassador to Cuba. Welles took up residence in an opulent suite in Havana’s Hotel Nacional, from where he exercised power behind the scenes not unlike British “resident advisors” in 19th and 20th century Indian princely states under the Raj.

Although nominally independent from 1903, Cuba was, therefore, in fact a US colony in all but name, run in the interests of the US. By way of analogy with the pejorative term “banana republic,” we may call Cuba a “sugar republic” with all the implication of foreign economic domination and domestic political corruption that the term suggests.

As a de facto colony, Cuba was, moreover, a quintessential, textbook case of economic dependency, according to UIUC Latin American historian Nils Jacobsen. Dependency theory, developed by South American economists in the 1970s, delineated the structural factors that produce and reproduce dependency between states over the long term. In Cuba, such dependency resulted from industrial sugar monoculture prone to the boom-bust cycle of fluctuating world commodity prices.

Cuba was even more economically dependent on the US than other Caribbean and South American nations for three reasons. First, it is located only 90 miles from the US. Second, its 11 million population is small. Third, it is also relatively small geographically. Physically, and especially economically, Cuba was literally dwarfed by the US and the US economy. And in politics and the economy, the Mafia played a big part in the 1940s, and especially the 1950s, working with dictator Fulgencio Batista (1933-1959) building nightclubs, hotels and casinos that made Havana a world-class sin capital — close enough to get to easily, but far enough away to avoid IRS reach.

Batista and Mafioso Meyer Lansky were best buddies from the mid-1940s until the 1959 Revolution. In 1946 Mafia kingpins met at the Hotel Nacional to strategize; Frank Sinatra flew in to provide entertainment. Batista offered a sweetheart deal. The Mafia would take over control of racetracks and casinos in Havana. Batista would open Havana to large scale gambling. With a $1 million investment in a hotel or $250,000 in a new nightclub, came a casino license that exempted investors from a background check, something required for gaming licenses in Las Vegas. To sweeten the deal, Batista offered a government match of dollar for dollar in construction costs beyond the minimum required investment, a 10-year tax exemption, and duty-free importation of equipment and furnishings. Lansky received $25,000 a year to serve as unofficial minister of gambling. Batista’s government got $250,000 for each license, plus a cut of each casino’s profits. Cuban hotel construction contractors with the right “in” made windfall profits by importing more materiel than they needed and selling the rest. Rumor had it that besides $250,000 for the license, a “sweetener” was required sometimes under the table. But what was there not to like?

At the Hotel Capri, up the street from the Hotel Nacional, part-owner George Raft, who played gangster roles in several movies, acted as the hotel’s “meeter-and-greeter,” and was memorialized in murals in the upstairs bar. Down the block at the Hotel Nacional, Meyer Lansky wanted to create luxury suites for high-stakes players in one wing of the 10-story hotel. Batista endorsed the idea over the objections of American expatriate Ernest Hemingway. A large framed photo at one end of the Hotel Nacional’s lobby memorializes the infamous 1946 Mafia meeting where they sit behind a roulette wheel flanked by bodyguards. Today, the Nacional hedges its bets and flies a large flag and poster of Che next to the mafiosi. Yet Mafia nostalgia exists alongside pre-Revolutionary colonial nostalgia.

Once the flurry of building was completed, Batista wasted no time collecting his cut from the new hotels, nightclubs and casinos. Nightly, his wife’s “bagman” collected 10 percent of the profits at Mob-run hotel casinos including the Capri. His take from Lansky’s casinos, the Nacional and Habana Riviera, was said to be 30 percent. Exactly how much Batista and his cronies received altogether in bribes, payoffs and all-around profiteering will never be known for sure. As for Lansky, he celebrated his first year’s $3 million in profits from the Habana Riviera on New Year’s eve 1958. That night the revolutionaries having arrived in Havana, looted and destroyed many of the casinos, including several of Lansky’s.

One of the longest, at 5 min. 32, and visually stunning tracking shots in all of cinema begins high atop the Habana Riviera with a parade of bathing beauties circa 1964, descends several floors below to the swimming pool, and ends with an underwater camera dip into the pool itself. A Soviet/Cuban production made by the director of The Cranes are Flying (1957), Mikhail Kalatozov, Soy Cuba (1964) was almost universally panned. For Cubans it was too stereotypical, for Russians it was insufficiently revolutionary, and in the West, it was largely unseen because Communist. It was “rediscovered” in the 1990s by those director-cum-movie historians Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola who relished its striking cinematic style. But representations are social facts, and scenes in Soy Cuba, such as the one set in a nightclub, capture the stereotypical 1950s Cuban decadence of sex, floor shows, gambling casinos and prostitution, not to glorify pre-Revolutionary Havana but to condemn it.

Today with the thawing of US-Cuban relations, Meyer Lansky’s grandson wants Cuba to reimburse his family for expropriating the Habana Riviera in 1959. “The hotel was taken from my grandfather forcefully,” he says. “Cuba owes my family money.” One commenter correctly states that this “is one of the most ironic and hypocritical statements I ever read. Meyer Lansky was a thug. He obtained what he had by force… used against innocent citizens. Lansky was a murderer and a thief, a leader of organized crime who hurt a lot of people.” His grandson “should crawl back under the rock from which he was spawned and shut his pie hole.”

Cuban Revolution

Cuba may be a small country, but in world historical terms the Cuban revolution warrants comparison with the other major peasant wars of the 20th century – Russia, China, Algeria Mexico and Vietnam. If the Russian revolution was Lenin and Trotsky, the Chinese Revolution Mao, then the Cuban Revolution has been Guevara and especially Fidel. Virtually synonymous with the Revolution, Castro was a charismatic leader for 45 years, one who exhibited an astute mix of doctrinaire revolutionism and pragmatism. In contrast, brother Raul is a pragmatist, and even technocrat, with decades of experience in the military managing economic initiatives ranging from tourism and agriculture to electronics and department stores (p. 377).

After all, it took a revolution in Cuba to challenge the very basis of American imperialism. To sever the ties of economic dependency required radical social surgery, a radical break with the US. No polite diplomatic papering-over of fundamental differences in political economy sufficed. Yet it unfolded in a series of tit-for-tat moves. Having mobilized the Cuban masses to topple the corrupt, dictatorial Batista government by 1959, Castro and the revolutionaries moved quickly in 1959-1960 to nationalize farms and businesses.

According to the revolutionary narrative, when Fidel and his fellow revolutionaries marched into Havana January 1, 1959, the first thing they did was close down all the casinos and destroy the gambling machines. The crowd on the streets simultaneously tore out every last one of the parking meters, an extra economic perq that had been given to Batista’s brother-in-law, an army general. And this is why there are no parking meters in Havana today.

To nationalization of US businesses, the US responded with the 1960 embargo. The story is that just before he announced the embargo, Cuban-cigar-lover JFK despatched his Washington press secretary, Pierre Salinger, to purchase all of the Cuban cigars he could find. Salinger returned with 1200.

The embargo was followed by the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion.

At a 1961 meeting Che thanked JFK aide Richard Goodwin for the Bay of Pigs attack. Earlier their hold on the country “had been a little shaky but the invasion allowed them to consolidate most of the major elements of the country around Fidel.” Goodwin asked if “they would return the favor and attack Guantanomo?” Laughing, Che responded, “Oh, no. We would never be so foolish as to do that” (pp 44-45).

The Bay of Pigs was followed in turn by the 1962 missile crisis, which brought the world to the brink of nuclear war, and solidified Soviet influence in Cuba. The revolutionaries also moved quickly on other fronts, relying on the same mass mobilization that had carried them to power. From the beginning, the revolutionaries understood that “Investment in human capital is not related to national wealth,” as University of Havana economist Giulio Ricci points out. “It is more a matter of political will.” With a literacy rate already in the high-70 percent range – higher than elsewhere in South America – the Revolution launched mass mobilization campaigns in 1960-1961, relying on the zeal of high school students working the rural areas, and quickly raised it to over 80 percent. Later, microbrigadistas were formed to build cheap, quick-and-dirty housing for all. Today, Cuba simply does not have the homeless problem that the US does.

In 1970 Castro wagered that the sugar harvest would top 10 million tons, and despatched thousands to the countryside to bring it in. The harvest fell short at 8.5 million tons, still a record. Cuba made a serious – many liberal and all neoliberal economists would say quixotic — effort to combat social inequality and level the socioeconomic playing field. Before 1991, for example, Cuban law stipulated that the “differential between the highest and lowest salaries in the country should be no more than five to one” ( p. 375).

Yet early on Castro was not a card-carrying Communist, and the Revolution was not particularly Communist. Yes, Castro was a nationalist and anti-imperialist. But the Communist Party was only one of three opposition parties; only in 1965 did it become the sole party.

Although the revolutionaries have stanchly maintained that “our system of governance” is non-negotiable, the economy has been hurt seriously by the embargo, costing Cuba an estimated $3 billion dollars annually. While there have been economic ups and downs, there has been little relative growth over the long haul. Nominally socialist, or communist, in fact the history of the Cuban economy since 1959 can best be described as two steps forward, one step backward.

What Havana wanted was to break out of the boom-and-bust dependency on commodities, tobacco but mainly sugar. Since the 1930s, such a major undertaking at playing economic catch-up has required strong state involvement anywhere in the world to join the industrial club, for example, Russia and China. Shifting to industry has so far failed egregiously. Revolutionary Cuba took a stab at centralized planning, but could not set realistic goals, could not compile accurate statistical data, and failed utterly. To his credit Fidel personally apologized in 1970 for 1960s lackluster economic performance. In 1981 the Soviet bloc decreed that Cuba forego industrialization and produce sugar. One of the bitter ironies of the Revolution is, therefore, that Cuba traded economic dependency on the US for dependency on the USSR.

Special Period, 1991-Present

Journalist Marc Frank argues that in the first three decades after 1959, the economy was better on balance, but it has not improved much, if at all, in the last 20-plus years. Economist Ricci notes that GDP peaked in the 1980s. What changed is, of course, that the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. As soon as the former UUSR cut off aid, Cuban GDP immediately plummeted 36 percent. Castro decreed a “Special Period in Time of Peace,” a political euphemism if there ever was one. Soon after, in 1993, Cuba instituted a dual currency system, one based on Cuban pesos, and one on convertible pesos called CUCs. One CUC was valued at $1 USD, or 24 Cuban pesos. Dollar circulation was made legal thereby, which meant that dollar remittances from Cuban-Americans to Cuban family members were now legal, which significantly boosted the economy after the end of Soviet aid.

During the early Special Period years, Cuba also lacked imported oil to run tractors, cars and buses, as urbanist Miguel Coyula observes. Cubans switched to bikes both built in Cuba and imported from China, plus bus-trailers made from converted semi-truck flatbeds that carried up to 300, and that were called “camels” because they had two “humps.” Having bought the argument favoring industrial agriculture – the hook of seeds, line of fertilizer, and sinker of pesticides — Cuba switched during the Special Period largely from industrial sugar monoculture to organic, sustainable agriculture, especially urban organic gardens, organopónicos. Although sugar remains Cuba’s main product, and it must still import 70-80% of its food, Cuban agriculture is ranked today fourth in the world in sustainability.

While these and other Special Period policies rescued the economy, economic inequality increased significantly. Few Black Cuban-Americans meant few dollar remittances went to Afro-Cubans, for example. Plus, the dual currency system planted a long-term economic depth-charge, because the exchange rates varied so greatly. As the economy improved, bicycles were put away, and cars and regular buses reappeared. Yet today there is no consensus on whether the Special Period is over or not.

Certainly, internal challenges to growth remain, argues economist Ricci. Infrastructure is obsolete. Real wages are low. The narrow wage scale is a social good, but does not correlate with results. Doctors earn the equivalent of $30/month in the state economy, but chefs, for example, in the best private sector paladars, or restaurants, can make $1000/month (p. 375). Yes, there is full employment, but productivity remains low. Public enterprises low in productivity employ 65 percent of the labor force. Agriculture practices sustainability, employs 16 percent of the labor force, yet produces just four percent of GDP.

The story is that the original owner fled Cuba in 1959 and left the early 20th century mansion to his housekeeper. By 2000 the ceiling was falling in from neglect, and the housekeeper’s son, Carlos Cristóbal Márquez Valdés, worked out an arrangement with the government to repair it. In 2010 owner and chef Cristobal opened it as Paladar San Cristobal.

“A New York loft-style lounge with a rooftop terrace, [the paladar] El Cocinero sits in what used to be a cooking oil factory but is now a chic venue for Havana’s cool crowds. The towering chimney still evokes the building’s industrial past…”

“A Spanish-style mansion in Vedado, with… colonial furniture in the main indoor lounge (even the silverware is antique) [that] provide the contemporary/retro backdrop of the [paladar] Atelier.”

Racism, Afro-Cubans and Santeria

Inequality, greater than before the Special Period, continues to increase, now fueled especially by Raul Castro’s 2011 economic guidelines, the Lineamentos de la Politica Economica y Social. Former diplomat José Viera and others worry that “tears in the social fabric” are increasingly visible (p. 374). Yet compared to other nations, including the US, Cuba still ranks high in social equality and human indicator scores. “The problem is that the new [2011] policies produce losers, because their chief concern is not social justice, but economic growth and survival,” says Alejandro de la Fuente, director of the Institute of Afro-Latin Studies at Harvard. “None of these policies is racially defined, but they produce new forms of social inequalities, and those inequalities tend to be racialized quickly because of unequal access.”

More generally, racism remains a serious problem. From its start, Fidel Castro’s revolutionary movement was dominated by middle-class white men. Historian Hugh Thomas notes that their ranks were so white that during initial clashes with Batista’s army, the government men were shocked when they came upon Castro and others hiding asleep in a bohío. ‘Son blancos!’ ‘They are white!’

Ironically, the island’s white elite before 1959 was so exclusive that only one social club, the Biltmore, admitted mixed-race, or mulatto, dictator Batista — he may have had some Chinese and Indian blood — and only after he paid a bribe of $1 million dollars. Even then members stayed away when he came around.

Significant advances have occurred. The granddaughter of slaves, Marta Terry González headed the José Martí National Library. Her nephew is editor of Granma, the official Communist newspaper. On the other hand, family remittances since the 1990s have exacerbated “socioeconomic differences based largely on race,” because they come primarily from white Cuban Americans and go mainly to their white Cuban relatives (p. 375). Racism figures importantly in the Cuban hip-hop scene. African-American FBI fugitive Nehanda Abiodun explains the working of race in Cuba.

“I am a lighter-skinned black woman. If I were to marry someone darker-skinned some people would describe me as ‘taking the race back’. If I were to marry someone who has European features I would be seen as ‘taking the race forward’. And if you do something worthwhile people might say, ‘Oh, that’s a very white thing to do.’”

That Afro-Cubans are primarily identified with practices of popular religiosity, such as santeria, known in Haiti as voodoo, does not help. Generally speaking, 15 percent of Cubans are atheist, 15 percent are religious, and 70 percent practice forms of popular religiosity. Key is that Catholicism in Cuba is not the same as Catholicism in South America, largely because of syncretism, the incorporation of non-Catholic elements. This can be seen in the main cathedral in Havana, for example, where a side altar features a painting of The Three Johns (Los Tres Juanos). It is said that the three boys saw an apparition of the Virgin Mary in Cuba. This eventually came to be seen as Ochun, the Afro-Cuban goddess of love and wealth. The two brass ores the boys are holding in the boat are actual tools used when making a shrine to Ochun. They are put in a bowl, sopera, along with Ochun’s other tools and stones. The ores are part of what are called fundamentos, meaning that they are required to make the shrine. “So,” as an anthropologist colleague puts it, “the painting more or less has a religious secret right there in plain view!”

Wearing all-white clothing, smoking fat cigars, their ritual objects and texts on display are one thing, but when such practices veer into animal slaughter and the like, many turn away. Such “colorful” folks and “folkloric” paraphenalia are evident in tourist spots, such as the cathedral square – where you can buy popular paintings of santeria adherents from sidewalk vendors — but likely are frowned on, if not condemned outright, in “polite” Cuban society.

Lineamentos de la Politica Economica y Social (2011)

Let us return and look more closely at the 2011 economic guidelines. They are just that, not programs, argues former diplomat Viera. For example, Cubans can now buy and sell homes. This leads by implication to a property tax, which leads by implication to an income tax, which leads by implication to a future inheritance tax. Individual housing units may now be owned, but no one is responsible for maintaining the building in which the units are located, so that they continue to fall into disrepair. The creation of a housing market leads, of course, to changing land values and more inequality. “Social segregation is due to land speculation,” maintains urban planner Coyula.

The guidelines also mean moving away from subsidies on goods and services, such as utilities, to subsidizing people instead. Instead of subsidizing electricity, for example, it is now charged on a sliding scale according to ability to pay. Ration books are less and less used, and government food stores are closing.

Now, if the value of all government subsidies is, say, a thousand dollars a month, the key question is where will the subsidy level be set? “The government says it will protect the poorer-off,” Viera says, “but the key question is protect at what level?”

Thus, Cuba is engaging today in a delicate economic balancing act. On the one hand, it cuts the wage rolls of the state bureaucracy and state-owned businesses to increase efficiency and productivity. It transfers certain under-performing state entities to the private and cooperative sectors. It ties wages more closely to productivity. It progressively eliminates the social safety net and economic subsidies for everyone except the poor. It has allowed a private, frankly capitalist sector – paladars (private restraurants), casas particulares (private B and Bs), alemntarde (privates taxis) — to grow to 25 percent of the economy.

Journalist Frank points out that business ventures that were once 100% Cuban-owned are now jointly owned, but with a minimum 51% Cuban ownership. The Hotel Capri, managed by Mafia front-man George Raft before the Revolution, nationalized in 1959, is today 51% Cuban-owned, 49% Spanish-owned, and 100% Cuban-managed.

Despite these and other changes since 2006 when Fidel passed the political reins to brother Raul, economic policy has remained gradualist and pragmatic. “I was not elected president to restore capitalism in Cuba nor to surrender the Revolution,” Raul Castro says. “I was elected to defend, maintain and continue improving socialism, not to destroy it” (p. 122). It remains the case, however, that in adopting the 2011 economic reforms, aka guidelines, the revolutionary elite has definitely revised the definition of socialism to mean “socialism of the possible,” as retired diplomat Viera says.

In the last 25 years, Russia, China, and Vietnam all have moved much further and faster away from socialism and towards capitalism. Cuba has not, so far, and on purpose. Reform may be the order of the day, a process, as Castro says, “without haste, but without pause” (p. 374). Journalist Frank asks, how did Raul get away with this shift? It is not communism where “everyone is equal,” but socialism where “everyone has equal opportunity.” Equality traded for opportunity – it sounds like that other “land of opportunity.” Granted, there is a consensus for change, but the key question is: for what changes?

Where Cuba stubbornly looks inward in pursuing its own economic path, it looks outward in other areas. Since 1959, it certainly has not cut itself off from the outside world. Far from it. Cuba is “a little country with a big country’s foreign policy” (p. 216). It has pursued an independent foreign policy, even while in the Soviet orbit. It did not ask Moscow’s permission before sending troops to fight in Angola and military advisors to Nicaragua to support the Sandinistas in the 1980s. Additionally, it sends thousands of doctors to work in Brazil, Venezuela and elsewhere. In 2011 there were 41,000 health workers in 68 countries (p. 218). Cuba created the Latin American Medical School, and offers free tuition to train students from abroad. Offering medical aid to the US after Hurricane Katrina — when George Bush and FEMA failed egregiously in their governmental responsibilities — was entirely in keeping with Cuba’s long-time foreign policy of “medical internationalism.”

At present, Cuba has forged bilateral agreements with numerous nations, and enjoys diplomatic relations with virtually everyone save the US. During the period from 1959 to 1979, there were 20 coups and dictatorships in the Caribbean, including the Dominican Republic and Haiti, but Cuba was the only country not colonialized. Five years after the Revolution in 1964 everyone had broken off relations with Cuba except Canada and Mexico. After the Cold War ended, US changed policy everywhere – no more military coups, or military dictatorships – except towards Cuba. Today, every country is multiparty except Cuba. The more democratic the Caribbean and South America became, however, the more the Organization of American States (OAS) welcomed single-party Cuba. As long-time, Havana-based journalist, Marc Frank, points out, US policy towards Cuba undermines its policy everywhere else in South America. Granted, this is now changing and changing rapidly. Yet it will literally take an act of Congress to lift the embargo, since Bill Clinton unwisely gave the final say to Congress in 1994, which simply ain’t gonna happen with the current Tea Party-controlled Republican Congress.

Culturally, Cuba looks outward as well as inward. From foreign policy to medical care to education, “Cuba is like a lightweight who fights in the heavyweight class – punching way above its weight,” and nowhere is this truer than in culture. Yet the “perception remains that Cuban culture is dogmatic and state controlled. This bias is widely held; it is also wildly incorrect” (p. 309). Yes, Granma is just the boring, no-news newspaper that you would expect as the “official organ of the Central Committee of the Cuban Communist Party.” Yes, cellphones are few in number and Internet access is woefully inadequate, although both are changing, and very rapidly. On the other hand, Telesur, a left-of-center mirror of CNN funded by Venezuela and broadcast throughout South America, arrived in 2013 (p. 314).

Cuba is certainly one of those places Americans know little about. This is largely because the US government and corporate media tell us so little. Misinformation and disinformation elbow out information. How many Americans know, for example, about the preferential treatment given to immigrant Cubans under the Cuban Adjustment Act (1966) compared to other in-migrants? It has been argued that Cubans are better informed about world affairs than Americans.

American culture permeates Cuba probably more than any other Caribbean or South American nation. It may be an exaggeration to say that there are more 1957 Chevys in Havana than anywhere else in the world – but not by much. American tourists who photograph Havana cannot take enough photos of big old American cars, “Yank Tanks,” – forget the no-longer-manufactured Soviet Russian Ladas and other makes on the road. To visit private garages specializing in keeping these decades-old cars running is like wandering onto a live broadcast, Cuban-style, of NPR’s “Car Talk.” With their fleet of over 20 pristine “clasicos,” the name of Nidialys Acosta and Julio Alvarez’s garage says it all: nostalgiacar.com. “Nostalgicar, makes you to live [sic] the dream of feeling into last century as our parents and grandparents did.”

American tourists trek to Ernest Hemingway’s haunt, Bodeguito del Medio, floor to ceiling with autographs and visitors’ photos from Dominican Republic dictator Juan Bosch to former Brazil president Lula to Nicaraguan Sandanista leader Ortega. On the street outside, you can buy a cheap, kitsch painting of where you have just eaten. On the outskirts of Havana, American tourists pay an obligatory visit to Hemingway’s home, which includes his boat that he wrote about in perhaps his weakest effort, The Old Man and the Sea (1952). We see Hemingway’s house through Cuban eyes in Tomas Gutierrez Alea’s masterful Memories of Underdevelopment (1968). Anti-hero Sergio, having elected not to leave for Miami after the Revolution with the rest of his bourgeois family, squires around Hemingway’s estate a mixed-race woman he has picked up, alternately trying to impress her intellectually, avoid existential boredom, and have sex with her.

After a hard day’s sightseeing, tourists staying at the Hotel Capri can get a drink in the lobby bar, but better is the upstairs bar with a Lucky Strike sign and mural paintings depicting George Raft, a Pan Am airliner, and a svelte woman smoking. Or the tourist can walk to Meyer Lansky’s former Hotel Nacional a block away, and drink in the outside garden looking out on the Malecon boulevard along the seafront, and the 1898 USS Maine memorial, not realizing that the American eagle adorning the top was torn down after the Bay of Pigs invasion and is now in the US embassy. Pre-Revolutionary colonial nostalgia combines with Mafia nostalgia, doubling your pleasure. Ah, the pleasures of imperialism.

Culture Plus

Next day there are options. Musicologist and musician Alberto Faya performs a brief history of Cuban music at venues such as the Restaurante Centro Asturiano. Lizt Alfonso Academy is a dance company led by women and school for youth. Founded 25 years ago, it has performed its distinctive fusion of Hispanic, African and Caribbean-style dance in hundreds of cities on five continents.

Songwriter Frank Delgado has traveled to a dozen countries, and sung in 120 cities. In Havana he performs at venues such as Café Madrigal. He is connected to novisima trova, heir to the nueva trova movement in Cuban music that emerged in the late 1960s, and that refracted post-Revolution political and social changes.

José Rodríguez Fuster is a world class outsider, or “naïve,” artist who has spent over 10 years rebuilding and decorating the town of Jaimanitas on the outskirts of Havana where he lives. Some compare his works in Jaimanitas to those of Antoni Gaudí in Barcelona, Constantin Brâncuși in Targu Jiu, Romania, and Nek Chand in Chandigarh, India. Fuster adds ceramic murals, domes, and other decorations done in his personal, idiosyncratic style to his own multilevel house with its various nooks and crannies, and to over 80 neighbors’ houses and other buildings, including a giant-scale chess park, doctor’s office, theater, and swimming pools.

Today, the tourist buses arrive with their CUC-spenders. Fuster, a one-person neighborhood development association. Fusterland, neighborhood-level economic development as art tourism.

Obsesión is primarily the hip hop duo and political activists Alexey Rodriguez and Magia Lopez. They started with break dancing during 1986-1990, when their musical influences included Marvin Gaye and The Miracles. The turning point for them, and many other youth was the abrupt plunge of the “Special Period.” While many unemployed simply hung out on street corners, a minority turned to art. The government supported groups financially, but some objected to following the government line. Supported by Harry Belafonte, who had spoken at length to Castro, Obsesión traveled in 2001 to New York where they performed at a hip hop festival.

Born in 1950, Nehanda Abiodun (Cheri Laverne Dalton) hooked up with the late 1970s/early 1980s “Family,” made up of remaining Weather Underground and Black Liberation Army members, the latter itself a splinter group off the Black Panthers. She allegedly drove a getaway vehicle in a 1981 Nyack, NY Brinks truck robbery in which three were killed. Declared a fugitive from the law by the FBI, she fled to Cuba in 1990. In 1999, she attended a hip hop concert that made her a fan, and she is now considered the “godmother” of rap, working with much younger groups like Obsesión on their “political education.” Concerning current changes in Cuba, she is “ambivalent.” She concedes that they are economically advantageous, but contends that they are “not a good experience for many young people.” Besides pre-Revolutionary and Mafia nostalgia, I guess radical chic persists, too.

All of these individuals and groups travel, mainly to the US and Spain. All this coming and going means different elements and styles are stitched together and mixed up in a transcultural stew (p. 312).

Colonial and Postcolonial Urbanism in Havana

The same could be said of Havana. Havana is one of the most distinctive colonial port cities in the world. Founded in the 16th century, it became a transshipment point for the Spanish colonial galleon trade, and eclipsed Mexico City in importance. Old Havana, la Habana Vieja, is small and compact. In 1982 UNESCO declared the entire old city a world heritage site. One of the most powerful and well-funded institutions is the Office of the Historian of Havana. Generally, there are few urban planners in Cuba, typically three per city, but Havana has 75. They work alongside a commensurate-sized staff tasked with renovating, repairing, and restoring the deteriorating, eroding, crumbling, falling-down building stock. The Office of the Historian is self-sustaining, because it owns title to everything in Habana Vieja. This means that the “city doesn’t have to sell its heritage to pay its bills,” observes urbanist Coyula (p. 12).

As with postcolonial cities elsewhere in the world, new government regimes often reverse the colonial past.

St. Francis of Assisi, built in 1739, has been converted into a concert hall. The current School of Arts used to be a golf course. The Presidential Palace, presided over formerly by Batista, is now the Museum of the Revolution.

Nostalgia for a golden age that ended in 1959 is not the only story some Cubans tell themselves. The Revolution has its story, its narrative, too. Alberto Korda’s iconic photo of Che Guevara (1960) is one of the most widespread, iconic and instantly recognizable political symbols ever. The Communist Party paper, Granma, is named after the boat that Castro and 80 other revolutionaries sailed from Mexico to Cuba in 1956. Upon landing, nearly all were killed by Batista’s troops. The survivors sought refuge in the mountains where they began an ultimately successful guerilla war, in what was the Long March of the Cuban Revolution. Images of the Granma are widely reproduced in a variety of media, including one by Fuster in Fusterland.

The original boat sits outside the Museum of the Revolution encased behind glass. Bullet holes in the walls from revolutionaries attacking the former Presidential Palace are carefully preserved. Inside upstairs, a lifesize wax diorama of Che Guevera and Camilo Cienfuegos represents them in the mountains.

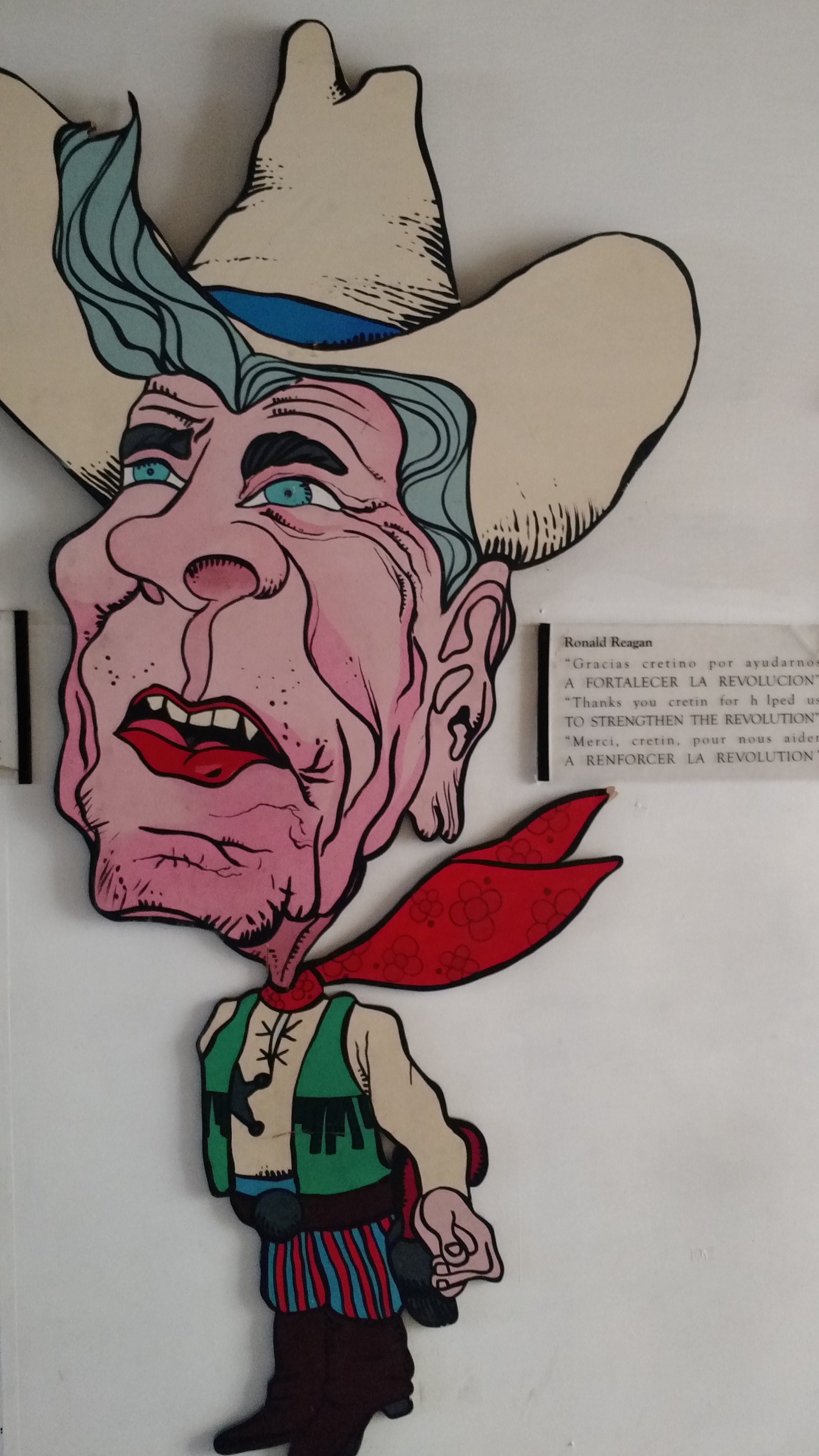

In a hallway downstairs, hang a series of lifesize rincon de las cretinos, “caricatures of antirevolutionaries,” including Batista, Ronald Reagan, and George H. W. Bush, and George W. Bush.

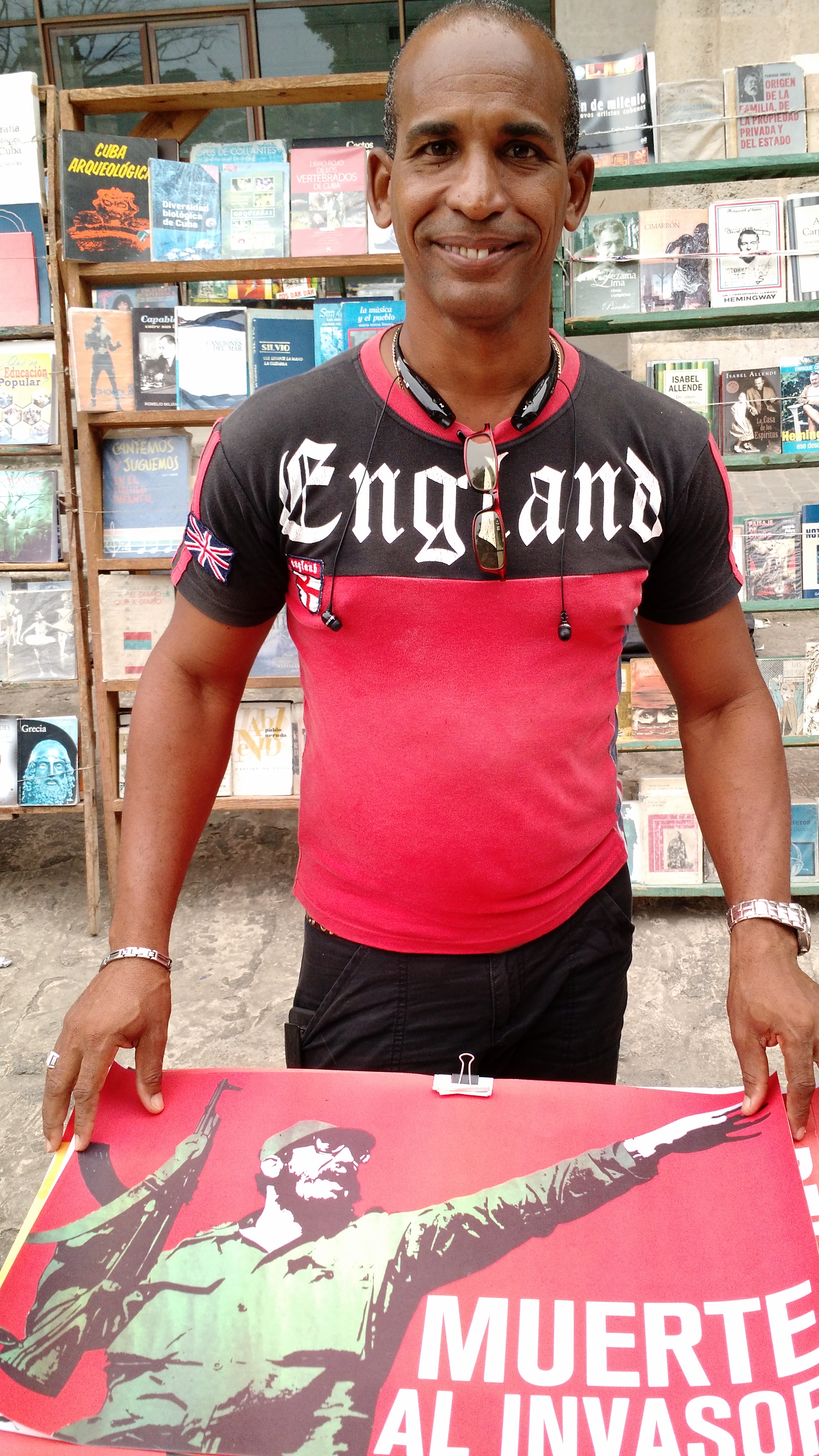

Back in Habana Vieja a block or two away from the Palacio Plaza de la Cathedral and the main cathedral’s syncretistic side altar of Los Tres Juanos, is the main touristic square Plaza de Armas. This is today the single most concentrated area frequented by tourists, where you can buy used books in outdoor stalls, cheap prints, and kitschy paintings. If you are not quick enough, the kid caricaturist will sidle up to you, dash off a not-bad likeness in seconds flat, and date it. All for three dollars.

From the old city core, Havana expanded, spilling over into the area now known as Vedado, and building up such suburbs as Miramar. Having eliminated the indigenous Taino inhabitants early on, the peninsulares poured especially their 18th and 19th century sugar wealth into urban architecture. First, they moved from their rural estates to Havana where they built so-called “social clubs,” based on the regions they came from. Later, they built lavish residences, some taking up entire city blocks. Add to that churches early and secular state architecture later, the National Capitol building, styled after the Panthéon (Paris), which looks similar to the U.S. Capitol, plus business edifices, such as Bacardi.

The result is that the architecture is more European than South American, because there were no Indians and indigenous influences. Unlike cities in Mexico and Peru, for example, there is only European architecture in Havana, which became “a piece of Europe in the middle of the Caribbean.”

Flashforward to the 20th century when between 1900 and 1958 80 percent of all the buildings in today’s Havana were built. A modern urban style, influenced by the US, became dominant by the 1940s and 1950s. Especially between 1956 and 1958, when the Mafia and Mafia money turned Havana into a “giant casino,” things changed overnight, and Vedado, for example, gained its modern urban skyline. As urbanist Coyula sums up, “Effectively a neoliberal economy, everything in Havana was driven by private capital; deep social and economic stratification and Mafia violence prevailed” ( p. 7).

The architecture of Havana is eclectic, the models European and international. What makes this transcultural stew Cuban is the distinctive mix of styles, often jostling side by side, the particular urban layout of streets and neighborhoods, the use of color, and, especially, the relative lack of gentrification. This can result, but not necessarily, in what urbanist Coyula calls Ar-kitsch-tectura, that is, merely flamboyant and over-the-top mishmash ornate.

Key here is that the Revolution eliminated housing as a business. In 1959 rents were cut 50 percent. In 1960 the Urban Reform law eliminated the housing market. For decades there has been no market-driven price. As pointed out above, you can own property but not the building. You cannot afford to maintain the building, but you have 20 years to pay for individual your property.

The result for urbanist Coyula is that Havana is the “last virgin city.” There is no drug problem to speak of, no homelessness comparable to the US. There is no neoliberal gentrification, no urban renewal. Not yet gentrified, there is no deserted downtown; it is a city lived in all over. Yes, the building stock is falling down, due to relatively little or no upkeep. The city is compact, walkable, “lo-rise, safe, non-violent, slow-paced” (p. 12). Importantly, there is less social segregation that elsewhere results from market-driven land speculation.

The other result is that old, ornate residences along with their civic architecture siblings are more often than not run down, if not falling down, dilapidated and crumbling. These two characteristics combine to produce an urban landscape that is “picturesque,” not to say “exoticist.” Stylistically, owners and their architects aped what was considered the best period architectural style, from 17th century Baroque to 20th century art nouveau. Mostly, however, they just spent money ostentatiously. Rather than particularly significant architecturally or aesthetically, they simply had built the most expensive buildings money could buy. Their size and scale, over-the-top flamboyance, and exuberant ornateness built to impress are indeed impressive.

All this architectural stock combined with an elite lifestyle spawns a very serious case of pre-Revolutionary nostalgia that the Cuban-American community plasters all over YouTube, and has yet to recover from. It also takes the form of glossy, full-color, large format books, among other things. But these publications crop out contemporary context. Interiors, some exteriors still stand, but the cityscape in which they were built no longer exists.

Another genre of publications focuses instead on the currently existing picturesque, exoticist urban landscape. These coffee-table works present a more accurate, but still skewed, view. It is an urbanscape worked on, and worked over, by countless individual Cubans public and private, who have combined to create what in many ways is an archetypal tourist dreamscape. “Colorful,” “folkloric,” “picturesque,” and “exotic,” this actually existing dreamscape is characterized by the tattered elegance of half-ruined buildings, juxtaposition and bricolage, what I call “preservation through decay,” and above all the use of color. We’re back to Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s 18th century Rome and Hubert “des ruines” Robert’s fascinated, and fascinating, romanticization of architectural and urban decay and decline.

The Havana so far of “preserved dipalidation” has created an already picturesque magnet luring tourists to visit. Unless Cuba and Cubans are very careful the tourist influx will erode, through tourist dollars, investment and gentrification, precisely that which the tourists came to see, just as surely as the sea air erodes the built environment.

Current Events

All of these urban developments are occurring against the backdrop of very rapid, recent political changes. Cuba and the Revolution have not collapsed, despite the US’s best efforts at regime change. These attempts range from economic embargo (1960-present), and the Bay of Pigs invasion (1961), to the more recent arrests and imprisonment of the so-called Cuban Five (1998-2014) for espionage (218). The Cuban Adjustment Act (1966) in effect encourages Cubans to emigrate with the lure of a quick and easy green card and enticing welfare subsidies unavailable to other immigrants as quickly. Perversely named after Cuban revolutionary José Martí, Radio Martí broadcasts from Florida? anti-Revolutionary propaganda. Hundreds of attempts have been made to assassinate Fidel Castro, including exploding cigars and a poisoned wetsuit (p. 2).

One part of the 2010 video game Call of Duty: Black Ops features a level set in 1961 Havana in which players try to assassinate Castro.

1959 Chevy Impala Secretary of State John Kerry drove in to reopen US embassy in Havana, August 14, 2015

Today, the last of the Cuban Five have been released, and Secretary of State John Kerry reopened the American embassy last August after 54 years. This is the backdrop against which the Cuban Five story played out. Given violent operations against Cuba, the Cuban Five were sent to infiltrate Cuba-American exile groups. Were they spies? Yes. They gained knowledge of plots about to unfold, and turned the info over to the FBI, since such actions are illegal under US law. What happened? The FBI ignored exile plotters, but used the info to trace those later dubbed the Cuban Five, arrested them and sentenced them to prison. One of the last to be released, Gerardo Hernández, got a personal, up-close, inside-view of American mass incarceration.

Gerardo Hernández, one of the last of the so-called Cuban Five released December 17, 2014, in Havana November, 2015

“The leading purveyor of anti-Castro terrorism” is Luis Posada Carriles (p. 331). In 1997 he organized bombings in the Hotel Capri, Hotel Nacional, and La Bodeguita de Medio. Twenty years earlier in 1976 he had masterminded the downing of a Cubana airlines flight that killed all 73 on board. During the Reagan administration, he supplied weapons to the Nicaraguan “contras” against US law. Today, Corriles freely walks the streets of Miami, his whereabouts, every move known to the FBI.

The “treatment of the [Cuban] Five contrasts with the way the United States has treated Cuban exile terrorists who live openly in South Florida” (p. 218). Your terrorist, my freedom fighter.

A Balance Sheet

Let me draw up a balance sheet. The problems outlined at the beginning of this article loom ever larger. Even as attitudes of the younger generations change – less virulently anti-Castro in Florida, less militantly revolutionary in Cuba – the unanswered question is: how many Cubans will choose to leave? The dual currency system is, for example, unworkable over the medium-term, let alone the long-term. On the one hand, disparities in the dual economy fuel both a black market in goods and services, and a gray market, where public workers will work at private sector jobs on the weekend. Such disparities, combined with a generally lower standard of living, engender corruption both economic and political. On the other hand, ending the dual currency system, and eliminating the CUC is tricky – at what value will the Cuban peso be set?

Or, to look at it another way, how does Cuba stack up for a Cuban weighing whether to stay or go? For many of the social measures cited above — healthcare, free education, infant mortality, income equality — Cuba outperforms the US. And while the US consumer economy and relative economic opportunity entices the would-be emigrant, they come with historically high economic inequality, a widespread system of mass incarceration and criminal injustice, systemic racism and continuing white supremacist attitudes, gun violence and mass shootings, social services shredded, and the nearly complete corruption of politics by money.

You pays your money and you takes your choice.

David Prochaska formerly taught colonialism and visual culture in the UI History Department