The popular film “Hidden Figures” tells a great story based on real figures, three important Black American women who work for NASA in key positions, as mathematicians and engineers, during the segregated 1960s. Contemporary audiences are celebrating this film that uproots stubborn stereotypes while reminding people that a severely divided America is nothing new, oppression and segregation have consequences, and with effort over time we may dismantle unjust barriers.

Black American culture has flourished sometimes far away from the limited view of the dominant culture, and this is certainly true of film. The purpose of this article is to highlight a small selection of excellent films by Black Americans that have remained hidden from many, but fortunately, not all.

Homage must be paid to the indomitable Oscar Micheaux, born in Metropolis, IL in 1884. After a stint as a Pullman porter in Chicago, he bought acreage in South Dakota and tried farming, and when drought led to crop failure, he wrote a novel about the experience and then in 1919 turned it into a movie, the first feature-length film by a Black American, The Homesteader. Micheaux was a pioneer in the production of films that were called “race movies.” Micheaux said, “Your self-image is so powerful it unwittingly becomes your destiny.” He understood well the influence of the movies.

Two eye-opening documentaries tell the story of race movies: “Midnight Ramble” (1994) and “In the Shadow of Hollywood: Race Movies and the Birth of Black Cinema” (2007). Get them on your radar. Required viewing is filmmaker Charles Burnett’s most notable film, Killer of Sheep. Burnett was born in Mississippi but moved to the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles and his film, set in Watts, shows us lives not often depicted on the big screen. The beautiful black-and-white cinematography of Killer of Sheep helps give it a neo-realist quality, meaning it feels authentic as it tells the story of a working-class family. The father works in a slaughterhouse, thus the title. It is not a horror film. Rather, through a series of vignettes, we experience the ordinary, yet deep, struggles faced by this family. Released in 1978, the film has recently been restored and its accolades accumulate. In 1981 the Berlin International Film Festival gave it its Critics Award; the Library of Congress declared it a national treasure in 1990, adding it to the National Film Registry; and The National Film Critics, in 2002, named Killer of Sheep one of The 100 Essential Films.

A second Charles Burnett film not to miss, also set in Los Angeles, To Sleep with Anger (1990), stars Danny Glover as an unexpected guest, an old friend from decades past and a world away who arrives from the Deep South to stay with a family and shows no signs of leaving. This trickster character brings superstitious discord with him and invades the comfort of modern ways emerging in the West. As one character tells him: “Harry, you know you remind me of everything that went wrong in my past.”

“Losing Ground,” the 1982 film by Kathleen Collins, described in 2015 by film critic Richard Brody as a “nearly lost masterwork,” is part of the Black independent film scene that included Charles Burnett. Unfortunately, the film did not receive theatrical release in 1982–showing once on PBS American Playhouse—but more recently has been made available on DVD thanks to Nina Collins, daughter of the filmmaker. (Sadly, Kathleen Collins died in 1988.) Ask your local library to add it to the collection as, masterwork though it may be, the film is hard to find, although it can be purchased. Described by critics as funny and brilliant, the story is about a marriage between Sara, a philosophy professor, and her husband Victor, an abstract painter. Collins, an author, filmmaker, film professor, and activist in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, is getting renewed attention thanks to the efforts of her daughter and others. Her lost collection of short fiction, What Ever Happened to Interracial Love?, was published in 2016 to critical acclaim.

Below are three recommendations that feature coming-of-age stories well worth seeing.

The Learning Tree (1969), written and directed by Gordon Parks, is a semi-autobiographical story adapted from Parks’ novel of the same title, and recounts his experiences as a teenager growing up in Kansas in the 1920s and 1930s. Gordon Parks was a photographer for Life magazine and Vogue, and this beautifully shot first film of his—he went on to direct Shaft and others—makes clear we are in the hands of a master photographer. The film looks and feels nostalgic but the story is steeped in substance. Much to learn under this tree.

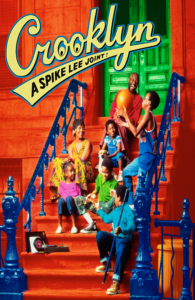

Crooklyn (1994), written by Spike Lee, his sister Joie Lee, and brother Cinque Lee, is a semi-autobiographical story about a family in Brooklyn with five children whose school-teacher mother (Alfre Woodard) grows ill and dies, leaving the jazz musician father (Delroy Lindo) as a single parent. Like all of Lee’s films, this one is vibrant with a great soundtrack and creative use of camera angles, and because of its closeness to Lee’s family history, this film has tremendous authenticity and warmth. Please note, in the section where the sister visits family in the South, her cultural and psychological displacement is highlighted by Lee with a distorted lens. No, there is nothing wrong with your screening device.

The Ink Well (1994), by Matty Rich, set in 1976 on Martha’s Vineyard in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, highlights class and political conflicts between two sisters and their husbands. One husband works as a social worker and was a member of the Black Panther Party. The other is a Republican who owns a fancy beachfront home on Martha’s Vineyard. The family with the McGovern sticker on their old car comes to visit the family with the Nixon portrait on the wall. The central character is the clever, odd (has a doll he talks to) 16-year-old son of the social worker, who learns teenage ways over the two-week visit and even (spoiler alert) loses his virginity to an older woman, quelling implicit fears that he might be gay, a dated aspect of this otherwise entertaining comedy-drama. The costumes and soundtrack designed to elicit 1976 culture are funky and fun. The title, The Inkwell, refers to a stretch of beach that has been popular with African Americans since the late 19th Century. The long history of African Americans living on Martha’s Vineyard is well worth researching. August 2017 will be the 15th annual Martha’s Vineyard African American Film Festival. Who wants to go?