By Janice Jayes

After four American servicemen were killed in in Niger in October, social media discussion fixated on President Trump’s insensitive remarks to the widow of one of the slain soldiers and questions about the logistics surrounding the unlucky mission. The focus turned the sad event into yet another chapter in domestic political debates, and, by dwelling on the most predictable issues surrounding the catastrophe, distracted Americans from a more serious question: just what is the U.S. military doing in Africa? Since 2001 there has been a dramatic expansion of U.S. military activity in Africa, but the shift can’t be measured just by the number of bases built, dollars allocated, or agreements signed. Most ominous is that Africa has become the proving ground for a new model of U.S. engagement with the post 9-11 world.

Figure: Niger, where the U.S. is building a $100 million dollar drone base and stationing between 400-800 troops, is ranked 188th out of 188 countries in the World Bank Human Development Index.

From Disaster in Mogadishu (1993) to U.S. Africa Command (2008)

For most of the Cold War era U.S. policymakers deferred to European allies on Africa. The U.S. assumed the former colonial powers had more interests in the region and, in any case, the need for Western solidarity dissuaded the U.S. from challenging Europe’s actions.

The Somalian famine in the early 1990s briefly changed the U.S. stance. The U.N. mission was caged in by militias seizing food aid for political exploitation and Europe was preoccupied with reinventing a post-Iron Curtain continent. The U.S., still flooded with testosterone from the successful intervention in Kuwait the year before, took on a new task of building a kinder, gentler world through military action, and sent the troops into Mogadishu. Unfortunately the mission ended in catastrophe, with the death of 18 Americans and hundreds of Somalis during the Black Hawk Down episode of 1993, and the Department of Defense put Africa back on the shelf.

The 1994 Rwandan massacres horrified the world, however, and raised questions about the morality of inaction from the country claiming the role of global leader in the aftermath of the USSR’s collapse. In response, the U.S. created the African Crisis Response Initiative to monitor and respond to crises like drought or ethnic cleansing. The new tool was subordinate to State Department control and mandated by Congress to work only with foreign militaries that met human rights benchmarks.

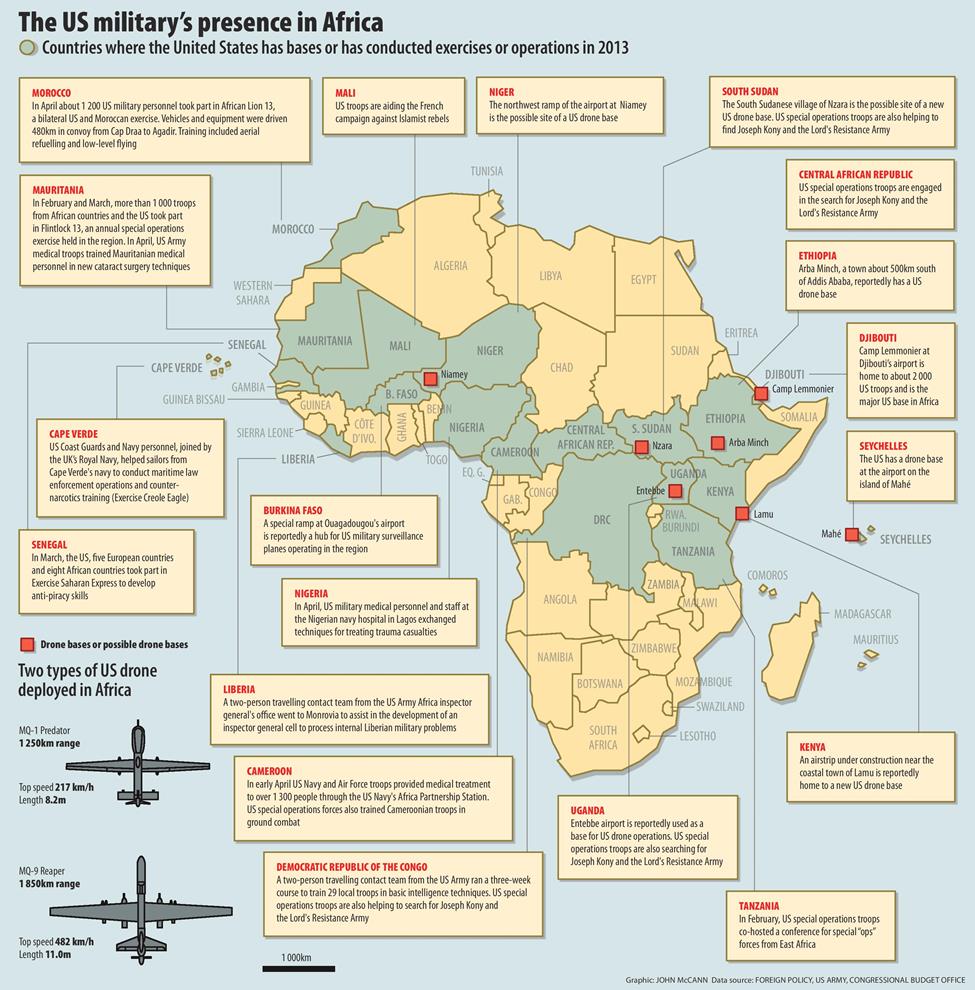

Source: Mail and Guardian, July 1, 2013. “Obama’s Scramble for Africa: US ‘Stability’ has ripped Africa Apart“ https://mg.co.za/article/2013-06-27-us-stability-has-ripped-africa-apart

The World Trade Center attacks of 2001 transformed U.S. policy completely. In Africa, the U.S. reliance on a small-footprint, crisis response team managed by State and situated outside the continent was replaced by a host of new military-to-military agreements. By 2013 the U.S. was running a network of dozens of military bases from Senegal to Somalia, training, equipping, and advising African military forces, establishing surveillance, improving infrastructure, undertaking joint exercises, and bringing African military personnel to the U.S. for training. The establishment of a separate “Africa Command” in 2008 marked the military’s institutional acknowledgment of Africa’s new status in U.S. defense planning. Surveillance, counter-terrorism, and tactical reach became the new buzzwords, pushing “nation building” and “human rights benchmarks” into the dustbin of history.

For ten years after 9/11, the U.S. followed a government-to-government military engagement pattern in Africa that replicated the U.S. pattern in other regions, but the events of 2011 pushed the U.S. into a new era. The collapse of the Gaddafi regime in Libya during the Arab Spring and the fragmenting of Al Qaeda’s global franchise into ISIS and other rivals were both symptoms of breakdowns in political control. Neither Gaddafi nor Bin Laden could manage their empires after the debut of the iPhone, and the ensuing chaos destabilized the entire region. Africa was reeling from the effects of the refugee crisis out of Libya, the collapse of the oil economy, and the flood of black-market arms flowing out of Libya. Finally, the September 2012 Benghazi attack, resulting in the death of U.S. Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens, convinced American policymakers of the need to adapt to “the New Normal” in engaging with a hostile and unruly world of multiplying threats.

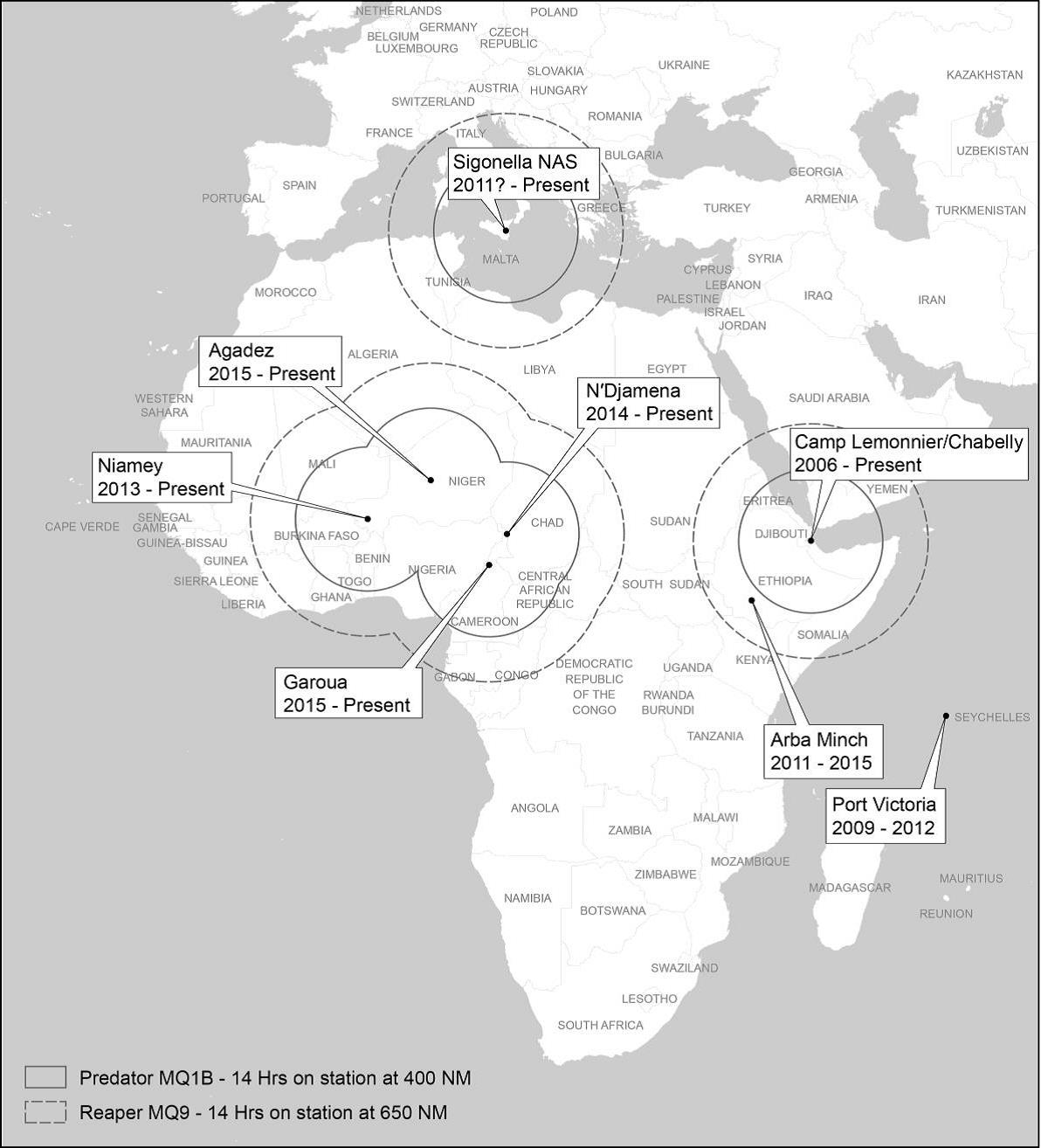

Fig: Drone and Surveillance (often run by contractors) bases are hard to research, but clearly multiplying.

Americans, mired in watching Congress hunt for a witch behind the Benghazi disaster, missed the most dramatic shift in American strategic practices in decades. Country-specific policies have been replaced by the centralized, decontextualized practices of the Global War on Terror. Drones and Special Operations Forces dominate the new mobile toolbox, both lauded as “fiscally sound” and “low-risk” means of projecting power in the new era. But it’s a policy built on punishment, not engagement.

Africa has provided the perfect laboratory for developing U.S. strategies for the post-Benghazi world. Except for with Egypt, there were no historic bilateral conventions to constrain reinvention. And there has been almost no domestic interest to drive congressional inquiry; most Americans pay scant attention to the world and even less to African nations. Couple that with the sleight-of-hand techniques that keep official numbers of U.S. troops low (special forces units are rotated in and out of regions and many tasks are outsourced to contractors), the overall shift in U.S. foreign aid from humanitarian and civil society funding to military programming, and the general lack of American interest in any action until there are American casualties, and you have a recipe for the unrestrained militarization of U.S. foreign policy.

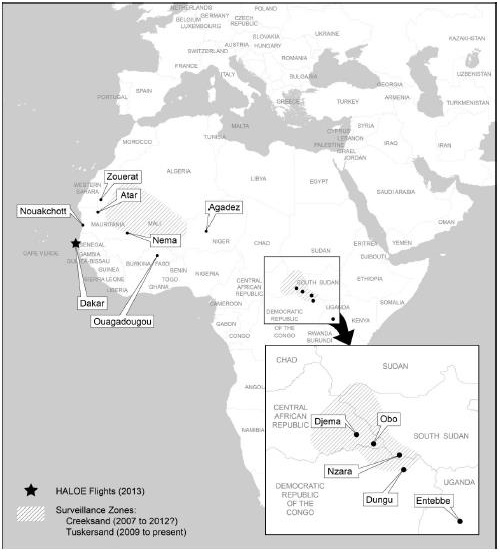

Fig: Manned, contractor-based ISR zones and sites in Africa. Source for both maps: Adam Moore and James Walker. “Tracing the U.S. Military footprint in Africa.” Geopolitics July-Sept. 2016.

U.S. military engagement with Africa has been quietly setting a new model for U.S. foreign policy in the 21st century, and the model isn’t pretty. We have the almost total eclipse of the State Department by Defense in setting the agenda, a narrow focus on “taking out” the bad guys and beefing up local security forces, and budgetary disregard for addressing the factors driving extremism, discontent, crime, or migration. Africa is not an isolated reserve for wildlife and security challenges, but a continent of 1.2 billion humans enmeshed in all the struggles the planet has to offer, both good and bad. Climate change, water scarcity, black-market arms and drug markets; rising expectations for health and consumer standards; the globalization of labor, investment markets, and the media; rising extremism and exasperation with government performance … the issues are familiar because we are all beginning to grapple with them. And yet our policy treats the continent as if it were a game park for terrorists.

Since 2001, and even more since 2011, we have seen the militarization of U.S. foreign policy. Surveillance and strikes have replaced the development of regional expertise, the promotion of civil society norms, the cultivation of economic links, and the creation of multinational organizations to address common challenges like piracy or disease. Those didn’t guarantee perfect policy before, but their disappearance has removed any balance from policy that views the entire region as a battleground in the war against extremism. Africa has become the testing ground for a new style of American policing of the world, and it isn’t going to provide security for us or the Africans.

Fig: Joint Exercises with U.S. and Malian Special Forces. Photo, Nick Sparks, AFRICOM. https://theintercept.com/2015/11/20/in-mali-and-rest-of-africa-the-u-s-military-fights-a-hidden-war/

Recommended Reading on the Militarization of U.S. Policy in Africa:

For a brief overview of the U.S. military commitments in Africa, see Katrina van den Heuvel, America’s Expanding Shadow War in Africa,” The Nation, Nov. 1, 2017. https://www.thenation.com/article/americas-expanding-shadow-war-in-africa/

On the growing role of Special Ops Forces in Defense strategy, see Joint Special Operations Research Topics, 2016. http://jsou.libguides.com/ld.php?content_id=13295950

On the DoD vision of the evolution of U.S. military relations with Africa, see DoD 2015 Senate testimony: https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/060415_Blanchard_Testimony.pdf and

On the lapse of “Human rights Benchmarks,” see Nick Turse, “The U.S. is Training Militaries with Dubious Human Rights Records – Again,” The Nation, Sept. 10, 2015. https://www.thenation.com/article/the-united-states-is-training-militaries-with-dubious-human-rights-records-again/

On the impact of the militarization of foreign policy on civil society in Africa, see Stephen Watts, “Identifying and Mitigating Risks in Security Sector Assistance for Africa’s Fragile States,” Rand Research Reports, 2015. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR808.html

On the budgetary shift in aid, see Helen Cooper. “White House Pushes Military Might Over Humanitarian Aid in Africa,” New York Times, June 25, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/25/world/africa/white-house-pushes-military-might-over-humanitarian-aid-in-africa.html

On the difficulties of researching the turn to manned surveillance and drone bases: Adam Moore and James Walker, “Tracing the U.S. Military footprint in Africa,” Geopolitics, July-Sept. 2016.