On November 25, Great Britain’s Prime Minister Theresa May returned from Brussels with approval from the other 27 European Union (EU) member states for a deal on Brexit, the British commitment to exit the EU pursuant to the results of the June, 2016 referendum. The deal is based on May’s Chequers plan, named after the official Prime Minister’s manor house where it was hammered out with her ministers this June, though it caused the resignation of her two most prominent hard-line pro-Brexit ministers, who saw it as a surrender of British independence and control over its borders. And further concessions were forced in the intervening months by the EU’s resolute position against making exit easy for any member, and by particular issues such as the dispute with Spain on the status of Gibraltar, and fishing rights in waters that could revert to British control.

The issue that has bedeviled the Conservative government’s position is the status of the border between the Republic of Ireland, which remains an EU member, and Northern Ireland, a constituent part of the United Kingdom (UK). A “hard Brexit”—a clean break with no special arrangements on trade and customs—would mean a “hard border,” disrupting Irish lives and relationships. Some even fear an unraveling of the 1998 Good Friday agreement that ended 30 years of sectarian violence. May’s Conservative Party is a minority government, relying on the support of 10 members of Parliament (MPs) from the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), which represents Northern Ireland Protestants. Critics see this dependence as rescinding the neutrality pledged by London in the 1998 agreement, after defending Protestant interests against the Catholic community during the decades of “the troubles.”

The solution embedded in the deal is known as the Irish “backstop”: the Northern Irish land border—and, by extension, that of the UK as a whole—would remain as it was, an intra-EU (non-)border with free movement of goods, until such time as the UK and EU agreed that such status was no longer necessary, either because a technological solution allowed “frictionless” trade or, more likely, because the UK entered into a long-term supplemental agreement with the EU. The EU refused to agree to the reestablishment of a customs border there, while the DUP would not countenance a special customs status for Northern Ireland, which would in turn entail checks between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK. Hard-line Brexiteers, including many in May’s own party, see the backstop as tying Britain to a customs union with the EU—and all the rules and laws it demands, including thousands of regulations on product quality, appearance, waste, environmental impacts and many other aspects—into the far future, and thus sabotaging the national sovereignty that Brexit was meant to realize.

Anti-Brexit demonstration

A parliamentary vote on the Brexit deal has been announced for December 11 [now postponed]. Despite intense campaigning, the May government will almost surely lose that vote. The EU says that no matter what happens in the British Parliament, it is not open to substantive renegotiation. The hard-Brexit Right—led by Boris Johnson, the brash Trump buddy and former Foreign Minister—hopes that by voting against the deal it can bring down May and replace her in power, and then carry through a “no-deal” Brexit, a clean break achieving full independence. (They call the May plan “Brino—Brexit in name only.”) Labour is also opposing the deal, hoping the Conservative government will fall altogether, and that it will win the triggered national elections. It offers vague promises to do better, to “negotiate a Brexit deal that brings Britain together, protecting workers’ rights, our economy, jobs and living standards.” The People’s Vote campaign on the other hand, supported by many Labour MPs, is pushing for a new Brexit referendum, hoping to overturn the 2016 result and keep Britain in the EU, based on a supposed “Regrexit” phenonemon (Leave (the EU) voters regretting their decision); polls do show a shift in the public mood away from Brexit, though the actual outcome would be anybody’s guess. The May government will likely continue to push to get its plan through Parliament, however many votes or revotes it takes, with some combination of concessions, however superficial, by the EU and fear stoked by the prospect of great economic dislocation and pain in the case of no deal by the March deadline.

Supporters of the campaign for a second Brexit vote

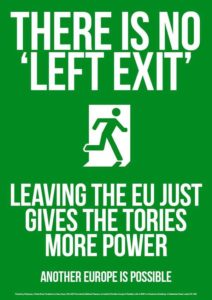

Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the revitalized Labour Party, a lifelong socialist and anti-imperialist, has always seen the EU as more repressive than progressive; he was criticized by the Remain (in the EU) side for the half-heartedness of the Labour campaign against Brexit in the runup to the original vote. His platform of “democratic socialism,” now solidified within Labour due to his swelling grassroots support and the party’s success in the June, 2017 snap election, calls for “renationalizing”—taking back under government control—key services, such as rail, post and water, in order both to improve service and stabilize employment and wages. Continued submission to EU laws could inhibit such plans, as well as other potential progressive policies such as capital controls and a reversal of the harsh austerity policies of the last eight years of Conservative rule. (Commentators differ on how much of a roadblock EU membership would be.) Political calculations also come into play: some one-third of Labour voters, concentrated in disadvantaged northern English and rural areas, voted for Brexit; and the 40-60 swing districts which Labour would need for the Parliamentary majority necessary to form a government and carry out its program showed a majority for the Leave side.

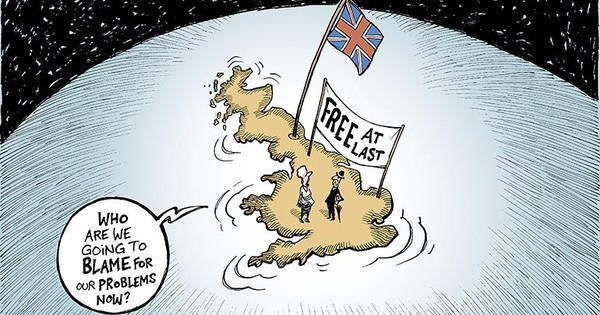

It is out of this milieu that the “Lexit” idea has sprung: a Left vision for a progressive Britain outside the EU. This position argues that the EU has been a throughly neoliberal and anti-democratic institution from the get-go. Despite its progressive facade—regulations on environment, waste, animal rights, tolerance, solidarity, peace etc.—when push comes to shove it will always side with corporations against workers and citizens. This corporate power and neoliberal orientation are embedded in the many layers of EU governance, making reform and resistance futile, and leaving individuals and their grassroots political organizations powerless. The EU is neocolonial, vis-à-vis the global South and the formerly socialist East, in fact exploiting any smaller polity: in the words of the late Marxist historian E. P. Thompson, then in reference to the EU’s predecessor, the European Economic Community, it is “a group of fat, rich nations feeding each other goodies.”

Lexit opponents counter that thinking that Corbyn can achieve his “socialism in one country” after Brexit is naive: it ignores, for example, the massive role that anti-immigrant sentiment and propaganda played in the Leave campaign. In a British economy dominated by the financial sector and beholden—even moreso than the EU—to neoliberal, low-tax policies, what is to prevent a truly independent Britain from, in the extreme view voiced by one commentator, becoming a “corporate-run, low-tax, zero-regulation criminal paradise”—and a racist and anti-immigrant one at that? The Labour Campaign for the Single Market (a faction within Labour, not representing the whole party) and its European counterpart the Democracy in Europe Movement 2025 (Diem25, as in carpe diem, seize the day), with its progressive superstar supporters such as Noam Chomsky, Julian Assange and Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek, are pushing for a revitalized, truly democratic, progressive EU, to disempower the ascendant European New Right and realize the values of peace, solidarity, equity and justice that the alliance is supposed to represent. But the experience of Diem25 founder Yanis Varoufakis, the former Greek Finance Minister in the Syriza government as it was negotiating the EU bailout of bankrupt Greece in 2015, offers a cautionary tale. After a resounding “No” vote (61.5%) by the Greek people on the EU bailout ultimatum, Syriza—without Varoufakis—went on to push through a bailout agreement not substantially different; Greeks are still suffering the consequences of the austerity it demanded. Whatever the outcome of Brexit, the EU and its citizens will continue to wrestle with the question of whether national sovereignty in Europe offers prospects for a progressive future.