Migrants trapped in Libya

In 2011, then-Vice President Joe Biden gloated to the press that US/NATO actions in Libya had modeled the new normal in warfare: an overpowering air and sea operation that accomplished the overthrow of an enemy government (Muammar Gaddafi’s) without sustaining a single American casualty. Nine years later, we are still watching the Libyan War, now starring freelance and Islamist militias, transnational criminal gangs, exploited migrants, meddling energy brokers, mercenaries and a host of other plagues. Americans should take note of the ongoing scramble for Libya, not just because we had a hand in creating the chaos, but because Libya could foreshadow the world ahead.

Perfect War and Imperfect Legacies

Biden was referring to a campaign ostensibly waged to prevent Gaddafi from crushing protesters, but equally concerned with protecting investments in Libya’s substantial energy sector. Western investment had only returned to Libya after 2003, when Gaddafi “came in from the cold” and announced his willingness to cooperate with international Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) inspectors. His pivot to the West ended two decades of U.S. sanctions and a European Union (EU) arms embargo, and Gaddafi quickly went from international pariah to most-favored global party guest, as countries competed to sign energy and arms deals.

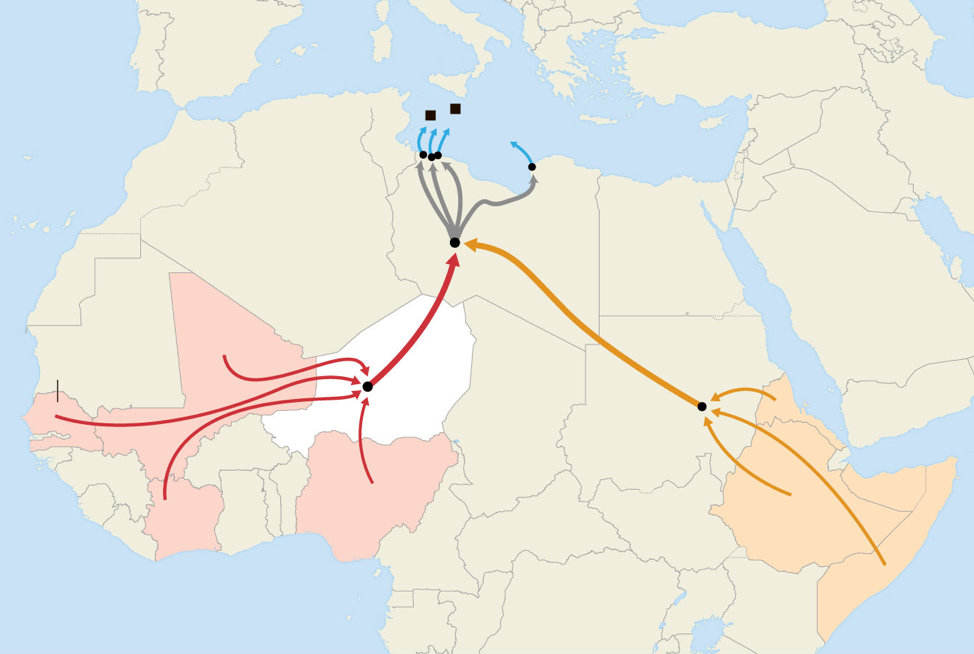

New money helped Gaddafi survive a few more years, but as the situation deteriorated during the Arab Spring, Europe worried that prolonged turmoil would devastate the energy sector. As Biden noted, the resulting NATO campaign modeled everything which modern warfare was supposed to be—speedy, high-powered, and remotely managed—but in retrospect the key weakness was the narrow focus on eliminating Gaddafi. In the aftermath of his death, weapons from Libya fell into the hands of militias, political rivals took to the streets and the anarchy of Libya attracted both jihadists and smugglers moving arms, drugs and humans north to Europe and south to Central and West Africa. NATO’s “perfect war” contributed to the collapse of the entire region, not just the regime.

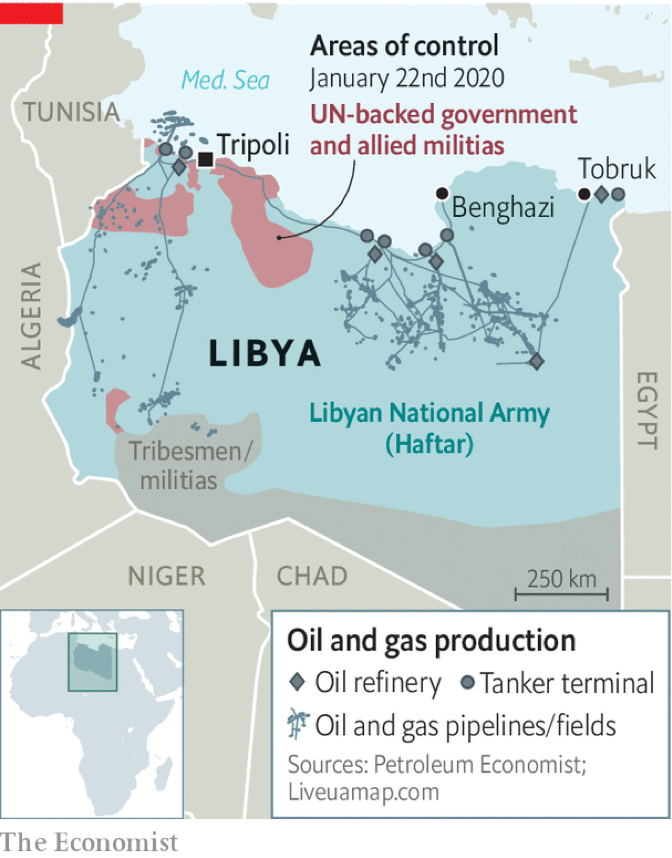

On most maps, the struggle for Libya looks three sided, but each block is made up of dozens of militias intent on controlling oil and smuggling resources

Fast-forward to 2020 and it’s the same civil war, but with a larger cast. There are some constants (Western aversion to Western casualties and a concern with the allocation of Libya’s energy assets), but the differences are a good indicator of what 21st-century conflicts will entail.

The Migration Crisis of 2015 Rewrote the Global Playbook

First, the Libyan war illustrates how the wild card of global migration is rewriting the global forecast. Migrants and refugees are certainly victims of war, climate catastrophe and structural abuse at the hands of the global economy, but they are also agents of change, showing their contempt for Western-imposed rules that bind them to untenable lives. The 2015 migration crisis shattered illusions of Western-controlled globalization in the same way that the OPEC price hike of 1973 shattered illusions of who controlled the oil market. The migration crisis opened fissures in the EU, and spurred the rise of right-wing nativist rhetoric on both sides of the Atlantic, ultimately leading Europe to reshape its Libyan policy around the need to keep migration contained, with a naval blockade and money for detention camps. The nation-building rhetoric of past decades was certainly ethnocentric and self-interested, but its replacement, “Fortress Europe,” is hardly an improvement.

In 2017 Oxfam and Doctors Without Borders accused the EU of complicity in the torture of migrants by pushing Libya to intercept and detain migrants under inhumane conditions

Flattening and Fragmenting: A Bull Market for Smugglers and Militias

Anti-migrant operations haven’t shut down smuggling networks in North Africa; in fact, non-state entities like militias have become entrepreneurial success stories. Easy access to weapons combined with communication technologies that allow small actors to instantly renegotiate routes, payments, products and strategic partnerships have transformed the political landscape. It’s an AirBnB- or Uber-style remaking of the war industry, eliminating the advantages of larger, more complex institutions in favor of smaller, more nimble actors with little stake in establishing traditional control over the land or population. In Libya, the labels “UN-recognized government,” “opposition” and “Islamist militants” ignore the mosaic-like reality of these fragile coalitions, and are thus the reason why negotiations continually fail to deliver peace. It’s tempting to deal with those who claim leadership as if they were in charge of monoliths, but the reality is empowered, decentralized and noncompliant actors with little incentive to reach a deal.

Smuggling routes that traffic humans and contraband to Europe also traffic arms back into African conflicts

Crumbling Norms of International Behavior

The multiplication of non-state actors evident in Libya, Syria, Yemen and other conflicts is accompanied by the increasingly addictive habit of cross-border state intervention. Despite a UN arms embargo covering Libya, Jordan, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and others have been openly funneling arms, including laser-guided munitions, drones and anti-tank missiles, into the conflict. In recent months both Russia and Turkey have deployed mercenaries, while the U.S. labels its troops as anti-terrorist forces. Proxy wars have never been so inclusive.

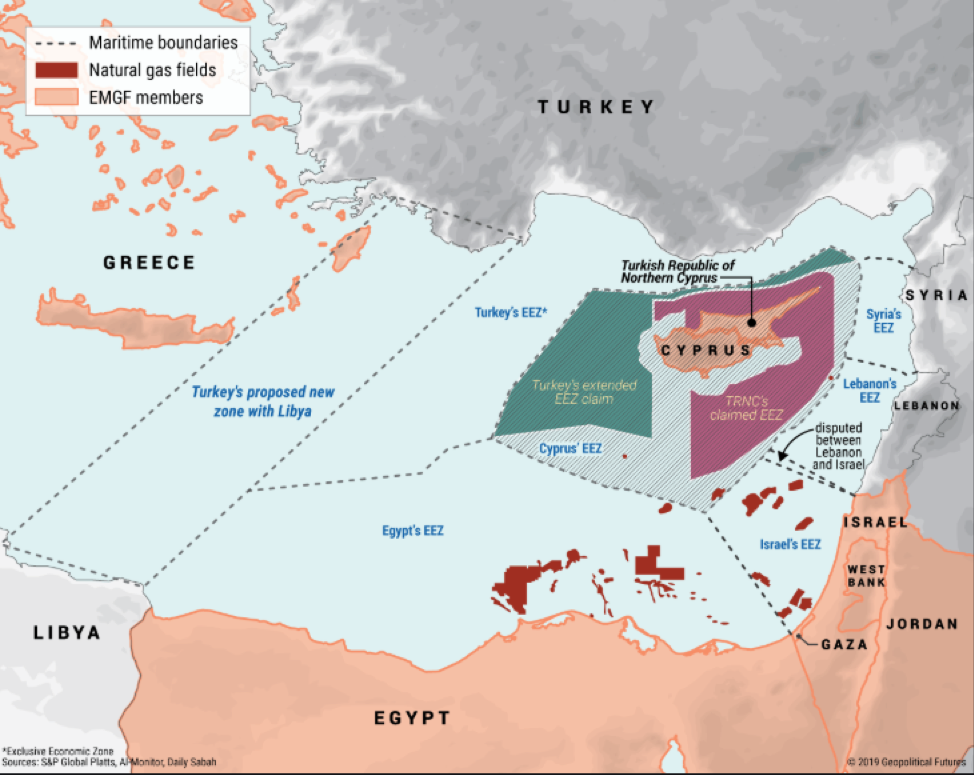

The Libyan conflict has spilled over to the eastern Mediterranean as well. In December, 2019, Turkey announced a deal with the recognized Libyan government that upended maritime legal conventions by carving out an exclusive Turkish-Libyan economic sea corridor. The announcement threatened previous natural gas and pipeline agreements, sparking condemnation from Israel, Cyprus and Greece, and prompting Egypt to dispatch troops to the Libyan border. Libyan opposition leader Khalifa Haftar displayed his own contempt for the international rule of law by blocking UN flights (including those supporting humanitarian aid) to Tripoli in February, 2020.

In November, 2019, Turkey and the Libyan National Government announced a shared maritime zone, prompting a flurry of protests from neighbors already disputing maritime natural gas claims and pipeline routes in the eastern Mediterranean

States have long sought to shape the world beyond their borders, but the brazen disregard for sovereignty and the international rule of law in the Libyan War is not a good sign. It’s hard for the U.S. to criticize, however (although Americans object vehemently to intervention waged through social media manipulation by other states), as it was the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 that sparked this new era. More recently, Trump’s tolerance for the Turkish invasion of Kurdish Syria, and ill-advised April phone call with Haftar, sent a clear message that there are no consequences for misbehavior.

From Winning Hearts and Minds to Controlling Resource Extraction Sites.

Finally, the low-minded goals in this war are perhaps the most disturbing portent of all. None of the combatants seems concerned with offering a plan for governing the 12 million Libyans. Peace conferences drone on about human security, but the competing militias, countries and companies are driven by the narrow aims of controlling smuggling and keeping the oil and gas flowing. We have seen this trend in the emergence of private militia-protected resource extraction sites in Africa in the last two decades, but Libya’s possible evolution into a landscape of gated community-like refineries set amidst a Mad Max world of disorder should be terrifying to all.

Libya as an Inspiration for Reinvention

Instead of seeing the Libyan War as a mess that needs to be cleared away before the future can begin, we should see it as the mess that might be the future if we don’t change. 20th-century rhetoric on international law and universal human rights was imperfect and often hypocritical, but do we really want to replace it with tolerance for the plantation overseers of the new world economy? For a situation where, as long as the pipelines, drilling stations, and ports are secure and pumping, and migration and human misery are kept under lock and key, no matter what fresh hell overtakes the lands beyond? It’s not just an immoral but an impossible model in a world of transnational challenges like crime, climate and pandemics.

We can abandon the imperialist doctrines of regime change and nation building, but we shouldn’t abandon the ideals of creating a world that supports human dignity and holds actors accountable for their behavior. Under the guise of the War on Terror Americans have done just that. We have chosen a path of engaging with the world primarily through the sights of a gun or drone. We have no choice but to be engaged with the world, but we need a new model of human-centered security for the times ahead. The alternative, as we can already see in Libya, Yemen and Syria, isn’t pretty.

Further Resources

Excellent overview of Libyan Militias: https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/kingdom-militias-libyas-second-war-post-qadhafi-succession-23121

Amnesty International on EU complicity with the abusive detention of migrants in Libya: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/01/libya-renewal-of-migration-deal-confirms-italys-complicity-in-torture-of-migrants-and-refugees/

The Atlantic Council on the contest to control oil and gas in the Eastern Mediterranean: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/energysource/gas-and-conflict-in-the-eastern-mediterranean/