Privately contracted paramilitary security forces have brought War on Terror techniques to the US, seen here at the Department of Energy Savannah River site

In April President Biden announced he was “ending America’s longest war” by bringing US troops home from Afghanistan by September 11, 2021. If only this war were that simple. Biden isn’t really ending the war in Afghanistan, of course: he is sliding the Afghan file into the cabinet of undeclared and unmonitored US military campaigns, like those in Yemen, Somalia, or Pakistan. It’s not a peace deal but an acknowledgment of a new model of unrestricted warfare waged with remote and secretive tools that will make the 21st century radically different from the world we claimed to be building back in 2001. The US–Afghanistan war isn’t just a tale of tragic human waste and lost opportunities, it’s a tale of transformation. It changed Afghanistan, it changed us, and it changed the way the world does the war business.

Choosing War in 2001

Americans claim the Afghan war was forced upon the US by Al Qaeda, but this is just creative reinvention. An invasion was not the only or obvious choice after 9/11, nor was it legally defensible. Al Qaeda was a non-state actor in a world set up around the principle of state sovereignty. The US argued that since the Taliban, the acting government of Afghanistan, did not hand over Bin Laden, the US had the right to topple the Taliban government and capture him ourselves. In reality, the Taliban had no more control over Bin Laden than the US had over the Unabomber; the demand was a mere pretext to buy time for an invasion the US committed to in the hours after 9/11.

The US could have chosen to pursue a criminal case against Bin Laden, as was done by Israel against Nazi war criminals, or by UN Tribunals against perpetrators of the 1993 genocide in Bosnia. This strategy might have taken decades, and it would have required the US to work with countries like Pakistan or Saudi Arabia to bolster the legitimacy of the process, and would probably have had to be carried out in absentia, as Bin Laden proved a wily target to the end. For all these reasons Americans would have hated the legal path, complained of its expense and lack of closure, and voted out any administration which pursued it.

Instead, the US chose an $800 billion war it claimed “degraded” Al Qaeda—but in what way? Al Qaeda’s strength was never in its fighters, weapons, or institutions, but in its ability to spread the idea that the US posed a threat to the region—and the invasion only fed that flame. Twenty years later the US is negotiating withdrawal with the Taliban regime it sought to vanquish in 2001, and the entire region has become a cauldron of anti-Americanism and spin-off extremist groups. How much worse could the frustrations of the legal path have been?

The US chose invasion partly out of the arrogant belief that it could manage Afghanistan better than the Afghans, and partly because Americans wanted to send a message to the world. The 9/11 attacks cost 3000 American lives; the US invasion of Afghanistan directly caused at least 46,000 Afghan civilian deaths, while hundreds of thousands of others suffered injury, death, or displacement. Neither the Afghan state nor the Afghan people were responsible for 9/11, yet the US chose invasion to display its might before the world.

The truth Americans cannot bring themselves to look at is that the US war on Afghanistan meets the definition of terrorism: the use of violence against non-strategic targets to send a political message. It is far more comfortable to recast the war in popular memory as a noble quest to root out terrorism, not as an act of terrorism itself.

The Afghan war provided the testing ground for the “over the horizon” war model now used in Somalia, Yemen, Libya and other undeclared US battlegrounds

From Failed States to Remote Warfare

At the beginning of the Afghanistan War the phrase “failed state” was wielded to justify invasion. In the 1990s the term emerged as a convenient label for places like Somalia where both security and domestic services had collapsed. The label put the blame squarely on the state, ignoring the ways global forces undermined state institutions around the world: the flood of weapons produced by and left behind by outside powers intent on manipulating local politics; long partnerships between external actors and corrupt regimes; or even the destabilizing inequality deepened by trade systems favoring global titans. No, rather than look at external meddling or economic imbalance, the 1990s prescribed a good dose of civil society workshops to strengthen failing states.

The “failed state” model was condescending and ethnocentric, but the abandonment of that model is no improvement. Since 2009 drone warfare has replaced the vision of the occupying army in US policy, and Biden’s commitment to withdrawing ground troops but preserving “over-the-horizon options” concludes that transition in the Afghan theater. It abandons even the fig leaf of pursuing decent government as a universal human good, and settles for turning Afghanistan, like Somalia or Yemen or other unacknowledged battlefronts, into a high-tech shooting gallery.

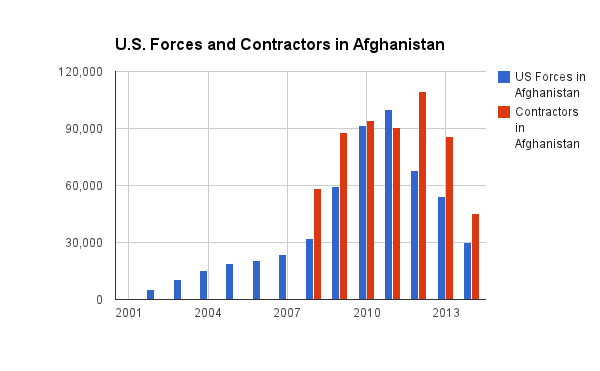

As early as 2006 Congressional and General Accounting Office reports expressed concern about the inadequate oversight of military contractors, but they grew to outnumber US troops in Iraq and Afghanistan

This is war on the sly. It isn’t secret war, for images shared by local witnesses provide enough information to map and record operations and drone strikes even when the US classifies the programs. But because the reliance on drone strikes and military contractors means there are few US troop deployments or casualties, there are few calls to congressional offices, and little incentive to convene investigations into the new model of warfare. For Americans, occasional reports of a “drone strike on militants” has become the scorekeeping soundtrack to a war with no territorial or political goals.

While the American public has little interest in the details of remote warfare, lobbyists representing the new industries—the surveillance, targeting, contractor staffing, and weapons production underpinning remote war—promote their craft in Washington. Remote warfare is the ultimate fantasy war for the military-industrial complex—churning out lucrative contracts that turn a profit whether operations eliminate enemies or inspire them. There is little citizen interest in drone or contractor-waged warfare, but a great outcry if budgeting is withdrawn and a business shuttered. This, sadly, is also Western-style democracy.

The demand for private security contractors in Afghanistan in 2008 fueled growth of a new industry and permanently changed norms of war in the US and around the world (Private Security Monitor graph)

The Last Helicopter Out of Kabul

The coming months in Afghanistan won’t be pretty, and the year after is likely to be far worse. But by that time Americans will be watching from a distance, comforting themselves with the thought that, despite their best efforts, the Afghans simply didn’t want to be modernized.

Sadly, the US modernized Afghanistan all too well. Biden’s shift to “over-the-horizon capabilities” completes the incorporation of Afghanistan into the 21st-century war paradigm. This is the real forever war, with no end even defined—just a long and lucrative projection of force that stokes anger against the US and erodes the remnants of the 20th century international system. The Afghan war provided the platform for reinventing war for other actors as well. More than 40 countries now operate drone programs; cross-border interventions are on the rise; and state sovereignty is brazenly flouted through cyberattacks, assassinations, arming of anti-government militias and even the placement of mercenaries abroad. This is the modern world the US helped build in the Afghan theater, and with the shift from a model of occupation and state building to remote war without oversight or rules, the modernization is complete.

Janice Jayes writes about migration and security issues, national and domestic. She teaches history at Illinois State University.