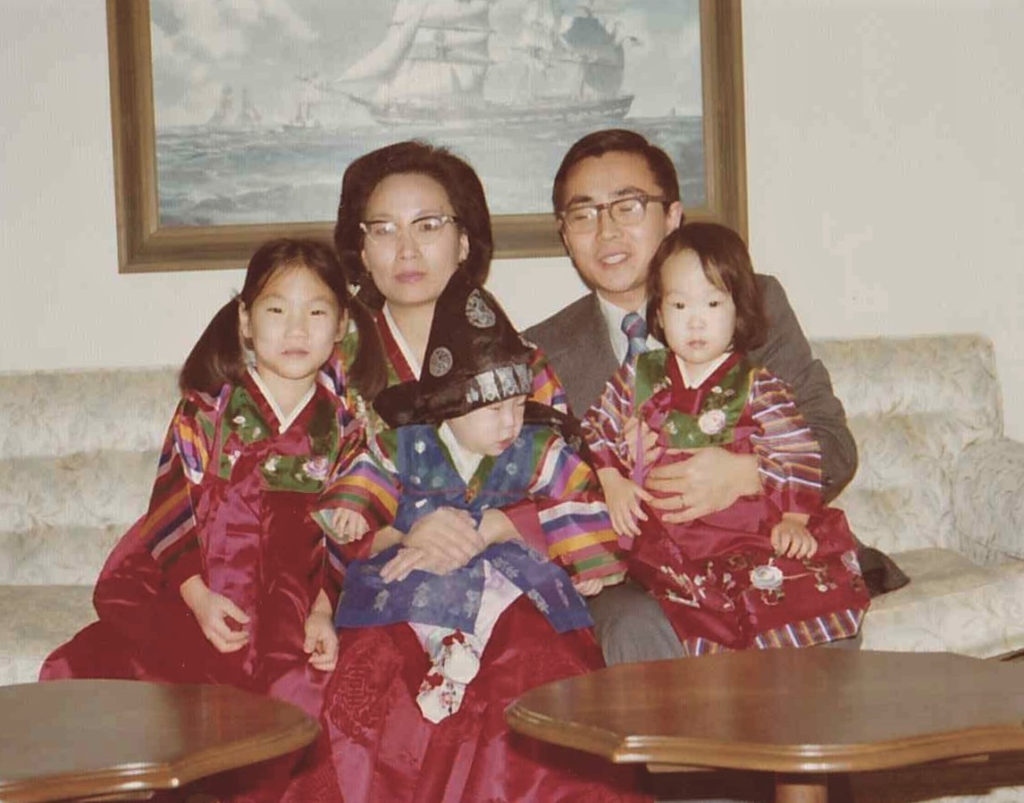

The author growing up in Cleveland (the middle child, on her father’s lap)

The March 16, 2021 shootings in Atlanta, resulting in the tragic deaths of eight people, six of whom were Asian women, have raised awareness of anti-Asian violence, misogyny, and hatred in this country. In this unprecedented time when global viruses of COVID–19 and racism run rampant, the rise in anti-Asian hate and violence cannot be denied. The national Stop AAPI Hate report documented almost 3,800 such incidents from March, 2020 to February, 2021.

Anti-Asian violence is not new. As a second-generation Korean American, born and raised in the Midwest, and a resident of Champaign for over twenty years, I was disgusted by the Atlanta killings but not surprised. News outlets daily document random violent attacks against Asian Americans, but this racism has always been part of the Asian American experience. Despite generations of citizenship, loyalty, and civic engagement in this country, Asians have been cast as foreigners, disloyal, and untrustworthy. Chinese immigrants who came to the US in the 1800s were vilified as taking over white labor, and mobs lynched them and drove them out of towns. During World War II, the US government labeled Japanese Americans disloyal, and rounded up 120,000 of them, two-thirds of whom were citizens, into internment camps. With US military involvement in Korea and Vietnam, media depicted Asians as the enemy and as dispensable bodies, collateral victims of necessary wars against communism; Asian women were presented as prostitutes who would “love you long time.” After the September 11 terrorist attack, South Asians became the newest target, suspected of terrorism, disloyalty, and hatred of America. The COVID pandemic’s depiction as the “China virus” and the “kung flu” is merely the latest iteration of this tired theme, blaming Asians for disease and justifying retribution.

Growing up in suburban Cleveland in a white suburb in the 1970s and 1980s, I was aware of racism when I was in kindergarten. My memories, like those of so many Asian American children, are filled with kids chanting racist names, pulling down their eyes to mock mine, making fun of my sister’s “flat face,” asking if I spoke English or where I was really from—the list goes on and on. I knew that people saw me as an oddity, as someone who did not belong. Even as I did well in school, the image of my being a model minority, obedient, and passive still painted me as other.

Being from the Midwest, I always knew that being Asian meant I was a person of color. I was not white. I identified with African American students, with civil rights history, with anyone who was different. I navigated life from the margins, never from the center. My college and graduate experiences at universities in the Midwest acknowledged I was a minority, providing support programs for me and for students who looked like me. I began to see my experience was shared and to build a community with others for support.

Then I moved to the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, hired in 2000 to help build a new Asian American studies program. During my interview, I learned that the university did not consider Asian American students to be minorities, because they were overrepresented in enrollment compared to their proportion of the state’s population. Despite this dismissal, the university had committed to establishing a new Asian American studies program due to years of student activism. (It would open an Asian American cultural center in 2005). The notion that the university did not acknowledge Asian Americans as minorities, presuming them to be like white students, baffled me. I began to uncover the history of Asian American student activism that challenged this notion that Asian Americans were “just fine” and needed no support. This discovery turned into my dissertation (and forthcoming book) examining the experiences of Asian Americans as the “unseen, unheard” minority on campus.

Asian American students, from the early 1970s through the late 1990s, battled the idea that they were not minorities. Measured solely with statistical representation, the university deduced that Asian Americans were thriving. But students objected, attesting to the daily experiences of racism they faced, the unique cultural conflicts with their immigrant parents they negotiated, the strong desire they had to learn about their own histories, languages, and cultures that were not covered in the university curriculum. They wanted faculty and staff who looked like them, who could relate to their experiences and struggles. Like the African American, Latinx, and Native American student activists before them, they advocated for a university where they had a voice. Most importantly they wanted recognition as students of color.

The sheer notion that Asian Americans are not minorities, that they are like white Americans in measures of success and achievement, astounds and infuriates me. Hailing Asian Americans as model minorities is a racial mascoting that shames other communities of color (this notion is internalized by Asians themselves, and reifies a racial hierarchy that places whites on top.) The model minority idea also ignores the racism that persists against Asians, or it says it’s not “as bad” as that experienced by other groups. The model minority myth divides communities of color to bolster white supremacy.

Uncovering Asian American student history empowered me to see how activism can bring about important change on campus. But while these students and their faculty, staff, and community supporters gained the resources they wanted, anti-Asian racism persists in Champaign–Urbana. In my twenty-plus years in the community, I admit I have been pretty lucky. Most of the time I can go about my daily life not having to think about the racism or sexism I might face. But when it inevitably happens, it reminds me that I am Asian American, and I do not enjoy the privileges of whiteness. In my years in this community, I have witnessed the July, 1999 shootings by a white supremacist (who had attended UIUC) in Illinois and Indiana; a spate of robberies and sexual assaults in fall of 2002 targeting Asian women on campus; Suburban Express advertisements in December, 2017 for [white] “passengers who look like you” and “not like you are in China”; and the June, 2017 abduction and murder of international student Yingying Zhang. My experience includes the daily racial microaggressions that happen, such as the man who I cut off in the grocery parking lot (I admit, it was my error) who berated me and told me I couldn’t drive like that even if it was okay “where I come from”; or the creepy white man who tried to befriend me in the library, telling me my eyes were pretty. These experiences enrage, terrify, and disgust me. They are a constant racial reminder.

The emotional work of dealing with racism is the toll that people of color must manage. My hope is that awareness will increase that Asians do face racism, that they are NOT white, and that they are people of color. It is a time to raise marginalized voices so they may be seen and heard in their complexity, and as people who belong and are entitled to equal protections as Americans.

Sharon S. Lee, PhD. earned her doctorate in Educational Policy Studies from the University of Illinois. Her research and professional experience focus on the history of higher education and the experiences of Asian American college students. Her book An Unseen Unheard Minority: Asian American Students at the University of Illinois will be published by Rutgers University Press in Fall 2021. She is Adjunct Assistant Professor of Education Policy, Organization, and Leadership, UIUC.