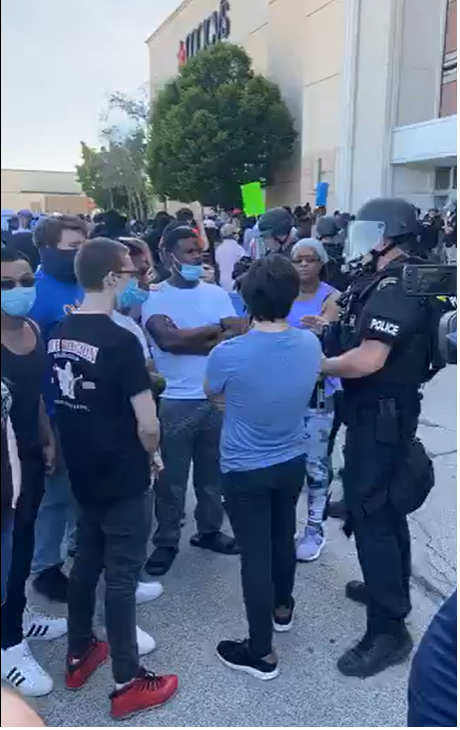

While some at the Mall committed property damage and theft last year, there was no violence and no confrontations with the police; many at the Mall carried protest placards

I watched the legal machinery eat further into the life of a young man this past month. On June 14, I joined others at the sentencing hearing for Shamar Betts at the federal courthouse in Urbana. Betts is accused of “inciting a riot” by posting on Facebook last May. Public defender Elisabeth Pollock petitioned the judge for a sentence of time served—Betts has already spent more than a year in custody—and a special assessment (fine) of $100. Two years of supervised release would serve the public interest by allowing him to participate in counseling and educational opportunities, and be in line with the sentences given other defendants charged in the wake of last year’s protests. In contrast the United States, represented by prosecutor Eugene Miller, pushed for a five-year sentence, three years of probation and restitution of $2.2 million for property damage.

After four hours of testimony the hearing was continued to August, but the unresolved dispute was not really over numbers, but over who should bear responsibility for the outrage that swept across Champaign and the entire country last year.

In the defense’s commentary (pre-hearing submission), it was the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police that triggered local and national unrest last May. In contrast, the prosecution blamed Betts alone for sparking disorder in Champaign. In fifteen pages of the prosecution’s commentary, Floyd’s name is never mentioned. Their commentary mentions ongoing “civil unrest,” but only to frame Betts’ action as if he were taking advantage of a time of national vulnerability, rather than living through that watershed moment. It faults Betts for shaking the “confidence of the community,” but never acknowledges the effect the murder of Floyd and other African Americans in police custody had on the African American community. It is Betts that the United States holds solely accountable, ignoring the long history of racial injustice that led to that moment.

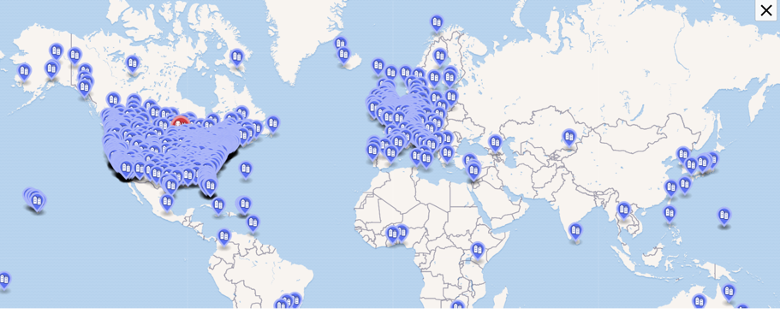

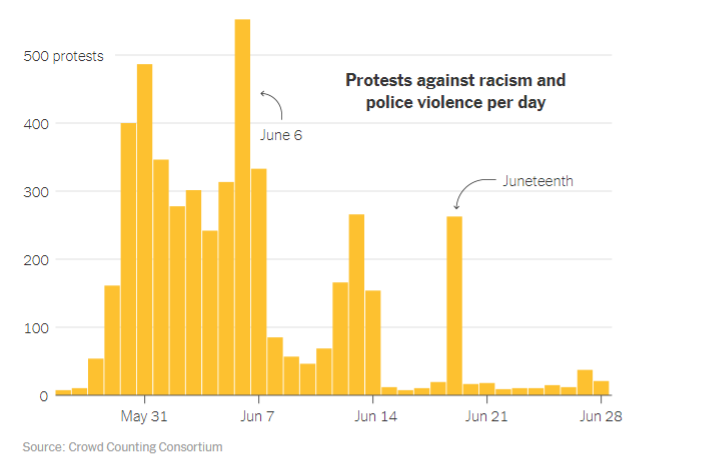

Protests following the murder of George took place in hundreds of cities worldwide. 23 states in the US called out the National Guard

Causality, Vague Terminology and Selective Enforcement

The prosecution called on three law enforcement officers (from the Champaign Police Department, the local FBI task force and the Federal Marshals’ office). as well as a local business owner to testify on the events of May 31. The testimony, based on surveillance notes and social media extracts, had the tone of a foreign situation report on a hostile uprising. For forty minutes texts from Betts were read aloud and “translated” to the court (as if phrases like MF and LMAO were an alien language and not standard teen texting vocabulary). The objective was to portray Betts as the puppet master of an insurrection.

Betts is federally charged under the controversial Anti-Riot Act (see Belden Fields’s article in the May/June 2021 issue of the Public i), a legacy of the 1960s effort to derail activism that specifically criminalizes the use of interstate commerce in the organization of a riot. Betts has already admitted to authoring the post, but the prosecution is required to prove causality in Betts’s impact on events. The prosecution repeatedly stressed that nothing like the Marketplace Mall riot had ever happened in Champaign before Betts’s post, nor since he has been in custody. The defense countered by highlighting the context of the unprecedented national reaction to Floyd’s death. Their point: property damage was occurring across the US and might well have occurred in Champaign even without Betts’s post, but it would certainly never have happened without the events in Minneapolis the week before.

On July 7, 2020 the New York Times estimated that the protests following the Floyd murder were the largest in US history

The Anti-Riot Act poses several problems for the prosecution, and the basis for a potential appeal. One angry Facebook post and some subsequent boastful texts hardly constitute proof of causality, or of “promoting” or “organizing.” In addition, the push to prosecute for social media communications precisely during the Black Lives Matter marches raises chilling questions about the selective use of Federal power over speech.

The prosecution’s push for five years also appears extreme compared to other cases. Defendants from the white supremacy group “Unite the Right,” who were arrested after organizing the fatal clash in Charlottesville in 2017, were sentenced to only 27–37 months under the Anti-Riot Act, despite having a history of having violently attacked peaceful protesters in other cities across the country.

All the wealth of the bondsman’s toil . . .

The prosecution holds Betts responsible for $2.2 million in damages to 73 businesses. They included the $100,000 cost of police overtime in the commentary, but apparently only to bolster the case for a five-year sentence, as law enforcement costs may not be charged to a defendant.

The defense objected in multiple ways: the US was tardy in submitting details of the restitution argument, documentation was missing, and the proposed legal guidelines primarily applied to fraud cases. It regarded overtime charges as spurious, as police departments across the country were calling in officers during this tense time. Finally, the defense objected to the inclusion of damage sustained miles from the Mall and long after Betts had left the area at 4:30 p.m. on the day of the unrest. Targeting one impoverished teenager with the price tag for community-wide damage defies reason.

The prosecution justified its harsh proposed sentence by characterizing the events of May 31 as a “riot” organized for the “very purpose of disrespecting the law, especially the laws that protect the buildings and possessions of local business owners.” The prosecution’s narrative erases the way both the murder of George Floyd and the larger legacy of racial injustices—in patterns of policing, economic dislocation and public disinvestment–contributed to national anger. This doesn’t excuse crimes committed by individuals, or claim that business owners deserve to pay for past injustices, but it does imply the need for a communal reckoning with the costs of racial injustice. The cost of May 31 belongs not to one young man, but to all of us.

Protesters at the May 31 demonstrations by and large showed calm, commitment and purpose

Personal and National Trauma

The defense stressed that Betts’s Facebook post was an uncharacteristic and since-regretted act by an adolescent (which Betts was at the time, according to the National Institutes of Health definition) who had made admirable strides in overcoming a traumatic youth. Expert witness Micah E. Johnson, Ph.D discussed Betts’s history of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE), a framework Johnson uses in helping police and schools shape strategies to support young people. Johnson documented the impact of trauma on Betts life in a closed report to the court, and emphasized his admiration for the achievements of a young man who was parenting himself by age 16. Despite struggling with food insecurity and homelessness, Betts finished high school and was a respected employee when the pandemic disrupted his life. His lack of youthful social resources also explain the poor choice he made in his May 31 post, noted Johnson. Betts expressed appropriate moral outrage at Floyd’s death through inappropriate means because that was the form familiar to him.

The prosecution countered by questioning Johnson’s credentials, challenging ACE scholarship, and attempting to recast Johnson’s testimony as proof that the defendant was predisposed to antisocial behavior. It did the same during testimony from Savannah Donovan, who hired and supervised Betts at the Urbana Park District. Donovan described Betts’s punctual appearance at work despite having to walk up to 11 miles a day to arrive for split shifts, and his patient manner. She described her concern for Betts once the pandemic eliminated his job, and her later knowledge of his suicidal depression in the weeks before the Floyd murder. The prosecutor, for no apparent reason, asked Donovan if she had ever “smoked pot with Betts.”

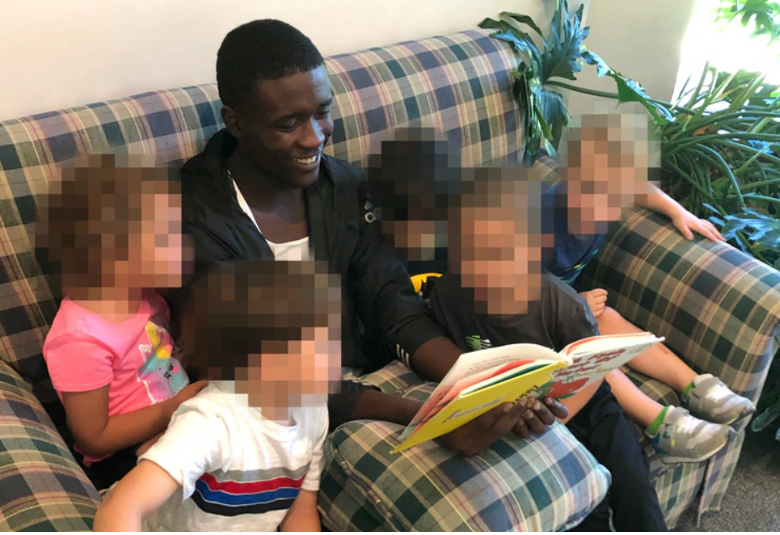

Before the Covid shutdown, Betts was a popular assistant at the Urbana Park District Environmental Education Program

Sadly, the prosecutor seemed successful in derailing the defense’s portrait of Betts as one of many overcome with uncharacteristic anger in the wake of Floyd’s murder. At the end of defense testimony the judge asked what he was to understand from the ACE report: was this a young man with a likely trajectory of future criminal activity? He appeared to have overlooked Johnson’s point that Betts’ personal achievements were remarkable, and that Betts had the potential to make great contributions to the community if given the opportunity to receive counseling and education.

The judge also commented on the dramatically different portraits of the defendant presented that day. How was he to reconcile the image of Betts, the patient and gentle employee, with the belligerent and vulgar texts of May 31? What could explain the disparity? Without an acknowledgment of the impact of Floyd’s murder the disparity can make no sense.

The Right to a Speedy Trial?

On July 8 the state theft charges were resolved with a sentence of three years probation, but after a year behind bars, Shamar Betts still has no idea what legal consequences he will face.

Betts personally committed no act of violence or destruction, has expressed regret for his manner of expressing anger after Floyd’s murder, and was not responsible for the underlying outrage that led to looting last May 31. Yet he remains behind bars, a convenient scapegoat for the government’s effort to deny any responsibility for the personal and collective traumas that fed the anger in the nation and the community last May.

For further background on Shamar Betts and the case, see my article in the March/April Public i.

2,761 total views, 3 views today