(National Guard troops were deployed even against orderly protests, contributing to Trump’s narrative of “lawlessness.” U.S. Army National Guard photo by Sgt. Jordan Trent)

On August 19, Shamar Betts was sentenced to 48 months in federal prison (minus 12 for time served) for authoring a Facebook post. The sentencing also made Betts personally responsible for repaying $1.5 million for damage committed by others at the Champaign Marketplace Mall on May 31, 2020. Each paycheck of Betts’s future income will be garnished until the obligation is met, turning the four-year sentence into a lifetime sentence of debt peonage and criminal branding as a federal felon.

This is a story of injustice in multiple dimensions, and the defense filed an immediate appeal. They will challenge the Anti-Riot Act, written explicitly to control political activity in 1968. They will challenge the imposition of restitution for all damage committed that evening despite the prosecution’s failure to prove the defendant was responsible. Finally, the defense will challenge the sentencing guidelines and the glaringly disproportionate sentence Betts received compared to others, such as those convicted in the Capitol insurrection. Michael Curzio, for example, had a previous conviction for murder, sported Nazi tattoos, and was a member of a violent white supremacist gang before storming the Capitol with the intent to disrupt Congress. He was sentenced to eight months and $500 in restitution.

Shamar’s sentence was meant to send a message, but in portraying Shamar Betts as a symbol of the “lawlessness” of the BLM movement the court has instead validated the deep distrust that African Americans hold regarding their ability to receive equal justice under American law.

Whose Words are Criminalized and Whose are Played on the Evening News?

Betts admitted to creating the post that urged people to come to Marketplace Mall last May. But it wasn’t Betts’s words, but the words that the mayor of Minneapolis and the Minnesota governor did not speak that sparked local and national anger. Four days elapsed after George Floyd’s murder before charges were filed against officer Derek Chauvin. Across the country thousands of protests erupted against police impunity, and it was this mobilization that brought national and international attention to the problem of police violence against African American men in the US.

Betts’s posts and texts, while not atypical for teens, sounded belligerent and even vulgar when read in the clinical atmosphere of the courtroom, but they were not the only words that could have been recited. Reading the transcript from the video of Floyd’s murder, including the heartbreaking plea for his mother, the joking of the officers, and the clear statement, “I can’t breathe,” would have given the anger that erupted on May 31 context. It is hard to find anything more obscene than the lack of respect for the law displayed by the police within the Floyd video.

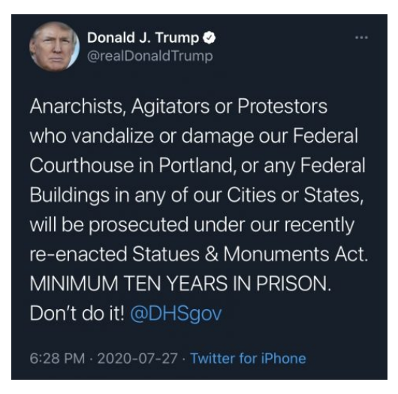

In the end the decision to ignore that context and hold Betts accountable for local damage, despite the failure of the prosecution to produce any evidence that actors were motivated by Betts’s post, exemplifies the discrimination in this case. FBI interviews with participants after the January 6 Capitol insurrection clearly document the role Trump’s speeches and social media posts had in setting off the day’s violence, yet Trump was not charged under the Anti-Riot Act or made responsible for the costs. Trump was merely banned from Facebook and Twitter for violating community standards, while Betts faces a four-year sentence and lifetime debt for his one post.

In 2020 Trump equated protest with anarchism and disorder in tweets that distorted the image of the BLM movement

Trump repeatedly used his presidential platform to distort discussion of the protests following Floyd’s death, and he had plenty of help. Media coverage echoed Trump’s “nuisance” narrative with words like “lawless,” “antifa” and “outsiders,” delegitimizing demonstrations and distracting from the key issue of police impunity by highlighting instances of property damage. In reality, BLM-affiliated protesters across the nation exhibited restraint even in the face of counter-protesters. Locally, thousands took part in BLM marches and only a few committed property damage in acts quickly condemned by local BLM-affiliated groups, who turned out to help clean up the mall the next day. Not only did later media emphasis on disorder mischaracterize the BLM movement, it distracted from the role right-wing groups and aggressive policing actually played. The Washington Post found such groups responsible for the majority of the post-Floyd violence. Trump’s rhetoric fed that violence in May as in January, but it is only Betts who faces consequences for his words.

Targeted Policing, Disparate Sentencing, and the Shrinking Space for Public Action

Multiple studies (by Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) at CUNY School of Law; the Prosecution Project; and PEN America among them) over the past year confirm that the 2020 BLM protesters were subjected to higher levels of law enforcement than right-wing groups. Unjustified mass arrests were made to shut down demonstrations, federal charges were applied instead of similar state charges, and longer sentences were imposed on BLM-affiliated protesters than right-wing protesters. Trump set the standard for this targeted treatment by encouraging the use of National Guard troops and deploying Homeland Security officers in cities across America. Trump even used unmarked units to detain people in what Oregon Senator Jeff Merkley condemned as authoritarian tactics. Trump’s fear-mongering and political baiting (encouraging supporters to vote out “weak” governors who failed to crush protests) were key factors in creating the climate of harsh and unequal policing.

Although more than 90 percent of charges against protesters were later dropped due to lack of evidence of lawbreaking, a publicly discoverable online arrest record alone can taint future encounters with courts and affect employment and education opportunities. Thus, the use of mass arrests is not merely a crowd control technique but causes economic damage to individuals.

In addition, many states are proposing and sometimes passing new anti-protest laws that are shrinking the space for political action. Onerous requirements for demonstration permits, the banning of face masks, and the re-categorization of misdemeanors (like blocking traffic) into felonies are just some of the proposed and passed new legislation. Bills also propose new penalties, such as the stripping of benefits (unemployment, voting privileges, or even educational aid) from those convicted of crimes related to protests.

While some of these bills appeared after the January 6 riots, most were written in response to the Floyd protests. This trend towards criminalizing protest began even earlier, however, when fossil fuel companies funded legal intiatives to criminalize environmental and pipeline protests starting in 2016. Moreover, the same actors promoting anti-protest laws are also central to the push to pass new voting restrictions. This widespread stifling of political participation is the face of political disenfranchisement in the 21st century.

Quantifying Damage: Persons or Property?

The way in which restoring respect for the law was narrowly equated with imposing a harsh sentence on Betts was the equivalent of a legal lynching. It used the destruction of one young man’s future as a lesson to the community. There have been legal consequences for those who engaged in damage or theft last May, but this sentence applied a politically motivated law, within the context of a politically motivated legal campaign, to highlight unrepresentative acts of destruction as a way of discrediting the entire movement to end police impunity. It valued the easily quantifiable damage to property over damage to the dignity of Floyd and all who watched that display of entitlement.

Betts is a young man and with or without early action on his case he will still be young when he leaves prison. In the meantime, the appeal will call into question the use of federal law to target political organizing and question the disparities in sentencing evident in his case. This, not an unjust sentence, is the way to restore respect for the law.

1,365 total views, 1 views today