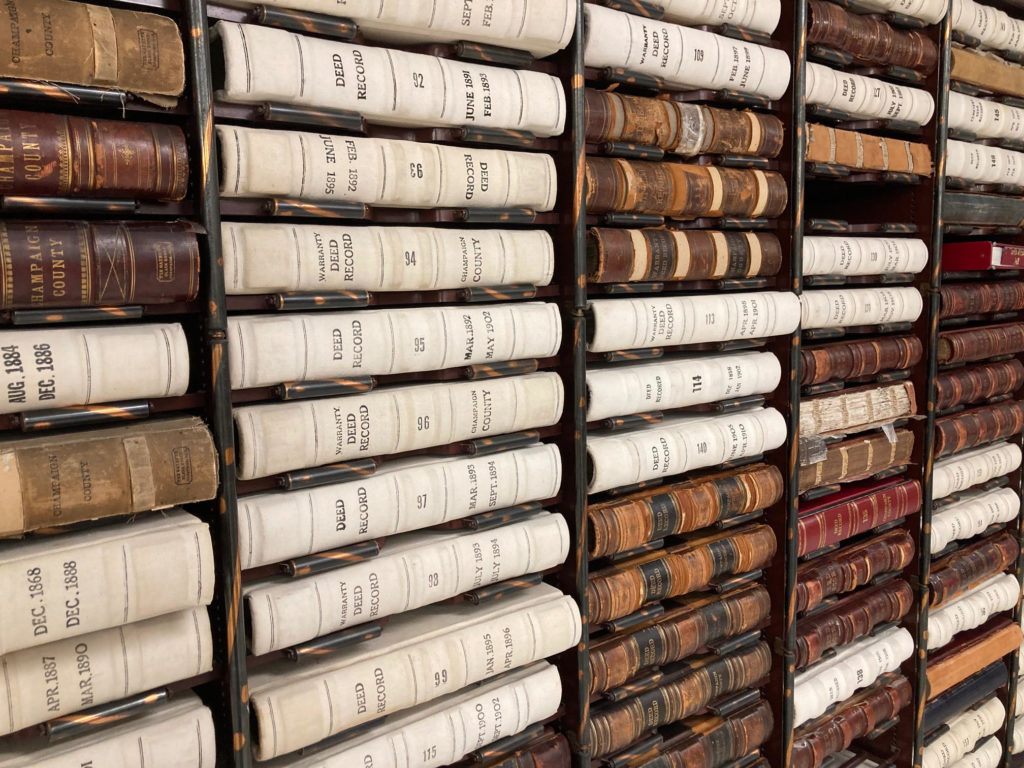

Champaign County Clerk and Recorder Aaron Ammons and Illinois State Rep. Carol Ammons (D-Urbana) examine land records

Can you imagine, as a resident of Champaign County, being told you aren’t allowed to live in a neighborhood because you’re Black? By today’s standards, such blatant racism would be met with disgust and rejection—at least by the majority of us.

But if you’re a student of history; you know about the torturous, inhumane treatment of Black people in this country through what is known as the transatlantic slave trade. You’ve read about the weaponization of laws after that period, resulting in the Jim Crow era of organized racism in the form of legal barriers to equality and terrorism committed against Black people by groups like the Ku Klux Klan. So when you hear that a resident couldn’t live on some properties throughout Champaign County, surely you imagine the age of Abraham Lincoln—a time long ago.

You would be wrong.

As recently as the late 1960s, Black people in Champaign County were legally barred from living in many parts of our community. Not only were Black people restricted from owning some properties, even renting or otherwise residing on such land was illegal. How could this be? It was done through the use of racially restrictive covenants.

Covenants are legally binding documents that construct the terms and obligations between two parties transferring ownership of land. A contemporary example of a covenant would be an owner selling property with a residential building, such as a house. They may apply a covenant to the purchase agreement to ensure that the buyer cannot tear down the house and rebuild for commercial use. Another example is the Champaign County Board’s decision to sell our once-public nursing home to a for-profit entity. A condition of that sale was the Board’s inclusion of a covenant requiring any owners of the former nursing home to operate it solely as a nursing home. We can see the power of these covenants today, as the bank which now possesses that land is currently appealing to the Champaign County Board to have that covenant dissolved, so they can offload the land to a purchaser for another use. Clearly, the legal weight of these covenants is significant.

For decades, some landowners in Champaign County utilized covenants for the specific purpose of keeping Black people out of the community. It was a means of maintaining racial segregation in an era where Black people had, through tireless struggle, fought for some modicum of basic rights.

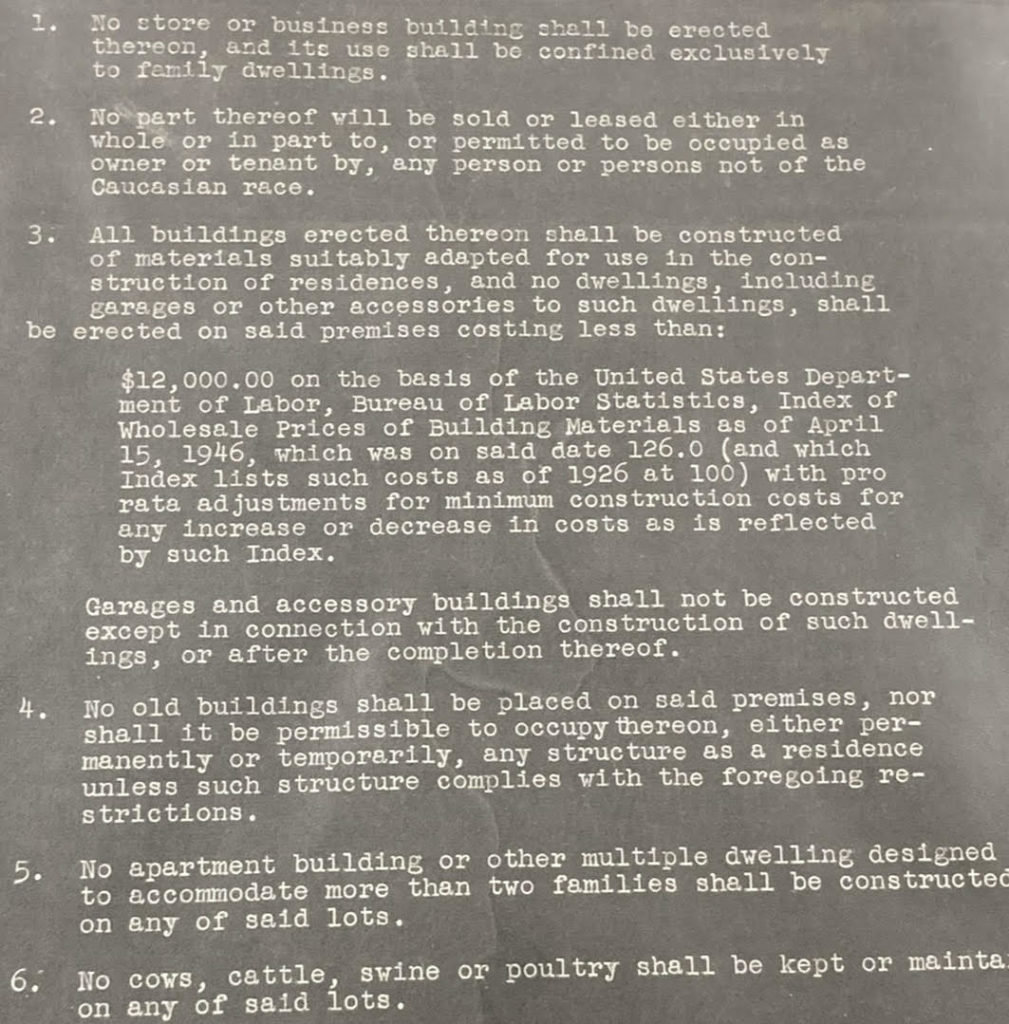

An example of a restrictive covenant found in the files for Champaign properties. Photo by Grant Chassy

The Champaign County Covenant Project, led by the Champaign County Clerk and Recorder’s Office, has been thoroughly researching these tools of racism. Thanks to the team’s hard work studying the entire land record, the existence of nearly 1,000 properties in the county that were once governed by now-defunct racially restrictive covenants has been uncovered. The vast majority of all these restrictions are written in the following language:

“No part thereof will be sold or leased, either in whole or in part, to or permitted to be occupied as owner, or tenant by any person or persons not of the Caucasian race.”

Because of the 1979 Illinois Human Rights Act, this kind of discrimination is now illegal. However, the Act merely nullified the effect of these covenants; they are still in the public record in the county recorder’s office. These records, while informing us as to the very recent history of racism, are also a road map to understanding structural inequity. In other words, restrictive covenants can inform us on how to repair the harm.

Champaign County land records examined by the Champaign County Covenant Project

Let’s assess just one example of the built-in racism these covenants illustrate: the public education system. In Illinois, our public schools are funded by property taxes. If you drive through Champaign County, the nice schools educate the nicer neighborhoods funding them, and the impoverished neighborhoods are left with the crumbling, underfunded schools. A 2018 study showed that this property-based funding has deprived black students of substantial resources: “School districts serving the largest populations of Black, Latino, or American Indian students receive roughly $1,800, or 13 percent, less per student in state and local funding than those serving the fewest students of color. . . . For a school district with 5,000 students, a gap of $1,800 per student means a shortage of $9 million per year.”

It is not an accident that Black students are more likely to be stuck in an inferior public school than their white counterparts. We know this because within the lifetimes of many of our parents, landowners possessed—and used—legal tools to prohibit Black people from purchasing homes in nicer areas, thereby condemning the Black community to the less valuable, less desirable homes and neighborhoods. Because of the property-tax funding model for public schools, the through line from racism to inequitable public education outcomes couldn’t be clearer.

While less obvious than the outright segregation of public education before the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, which purportedly desegregated schools, these racially restrictive covenants were a deceptive means of maintaining a segregated society. The proof of this, visible via the road map of the covenants, is bolstered by public-school data. Studies from as recently as last year show that white students graduate high school at a higher rate than Black students.

When we use racially restrictive covenants as a lens to view discrimination and structural unfairness, we see a glaring fact: racism is a built-in feature of American life. The conscious efforts people took in very recent history to subjugate African Americans require conscious efforts to be rectified. The answer to the broader injustices of racism is reparatory justice.

The city of Evanston, IL recently disproved what many in local public office would have you believe: that lower levels of government supposedly can’t afford or otherwise don’t have the power to make meaningful change. They are wrong. Evanston provides Black residents who lived in the city between 1919 and 1969, and their direct descendants, with up to $25,000 in either mortgage assistance, housing renovations, down-payment support, or direct cash payments. This is a mere drop in the bucket as justice for the hundreds of years of terrorism Black people were subjected to, but it is a welcome start.

Local governments in our area should follow Evanston’s lead, implementing a reparations program for our community. We must also support state and federal efforts to repair the harm through the monetary payments which can never fully heal what was inflicted, but help repair the structural wrongs black people continue to fight against to this day. Let’s learn from racially restrictive covenants and repair the harm.

Aaron Ammons has served as Champaign County Clerk since 2018, assuming office as County Clerk and Recorder in 2021 after the offices merged. In that capacity, he has led the Champaign County Covenant Project on racially restrictive covenants. He is a former president of SEIU Local 73 Chapter 119, a former member of the Urbana city council, and a lifelong activist. He also hosts the Higher Ground radio show on WEFT 90.1 FM.

Grant Chassy is a lifelong Champaign-Urbana area resident. He earned a bachelor’s degree in Political Science from Illinois State University. He is a former Deputy Champaign County Clerk and Recorder. He also produces and co-hosts the Higher Ground radio show on WEFT 90.1 FM.

1,230 total views, 1 views today