Dissident voices emerge from historical conditions of political crisis, social disruption, and economic betrayal. As social agents of revolutionary ideas, dissidents embrace a commitment to historical struggle as a life vocation. Those who emerge from the anguish of poverty and dispossession know only too well the need to be ever vigilant and conscious of how political power in society is exercised. Such scholars exist in direct opposition to myths of modernity that would have us believe that our world can only be genuinely known through dispassionate inquiries and transcendent postures of scientific neutrality, as defined by western philosophical assumptions of knowledge.

Dissident voices emerge from historical conditions of political crisis, social disruption, and economic betrayal. As social agents of revolutionary ideas, dissidents embrace a commitment to historical struggle as a life vocation. Those who emerge from the anguish of poverty and dispossession know only too well the need to be ever vigilant and conscious of how political power in society is exercised. Such scholars exist in direct opposition to myths of modernity that would have us believe that our world can only be genuinely known through dispassionate inquiries and transcendent postures of scientific neutrality, as defined by western philosophical assumptions of knowledge.

Instead, dissident scholars refuse to be extricated from the flesh and, thus, immerse us fully into the blood and guts of what it means to be alive, awake, and in love with the world. Instead of the boredom, isolation, and banality of contemporary mainstream life, dissident scholars seek places of imagination, possibilities, creativity, and Eros from which to live, love and dream anew.

However, the journey can be arduous and contemptuous. Dissidents must be constantly self-vigilant and formidably prepared to contend with a variety of obnoxious contentions and veiled obstructions that, consciously or not, serve as effective roadblocks to the wider dissemination of radical ideas and revolutionary visions. This is to say, that unless one is born into or is in alliance with the ruling class, the journey to voice for dissident scholars is an extremely precarious one. Many come dangerously close to losing heart, mind, body, and soul—all serious losses that can effectively disable dissident passion, make uncertain our faith, shed doubt on our intentions, and thus, immobilize the transgressive power of dissenting voices—voices absolutely essential to democratic life.

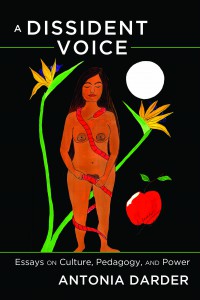

A Dissident Voice (Darder, 2011)

_______________

I offer the excerpt from A Dissident Voice as part of a reflection of my history with the Public i and the vision that I believe the paper attempts to nurture in the world. For over eight years, I lived in the Champaign/Urbana community alone and feeling alienated and quite the outsider. One of the few places where I found connection and where my voice and my ideas were welcomed was at the Public i, which over the years has worked consistently to publish a variety of voices on the margins and bring them to the center of the political discourse of this community.

This does not mean, of course, that in this process of collective knowledge production there were not moments of deep internal struggle or conflicts; for to be a political publication that embraces dissident voices means that there will always be struggle and differences, which must be engaged with courage and persistence. As would be expected, conflicts surfaced about many of the same issues we find in any context—racism, class privilege, gendered relations of power, homophobia, and even the sort of political elitism that can still rear its head among progressive people.

Yet, what I found rather extraordinary with the different folks associated with the Public i over the years, and especially during the time that I was a member of the editorial committee, was that most understood that conflict and political differences are essential to any democratic process, including the rethinking of political issues and community struggles. And although at such moments there were some who simply chose to walk away, those who remained came to learn much about what Audre Lorde called “that dark and true depth which understanding serves…this depth within each of us that nurtures vision.”

Moreover, if our voices of dissent were to challenge the powers that be, then we had to also accept that dissent had to be a welcomed dimension of our editorial dialogues and our efforts to bring a different vision of political life to the community. As such, over the years, the political analysis, sensibilities, and contributions of a variety of community members were documented in the pages of the Public i, leaving an indelible historical footprint of important and powerfully dissenting voices within Champaign Urbana—voices united loosely by a collective vision of social justice, human rights, and economic democracy.

Despite many monetary and organizational limitations, the paper’s uncompromising commitment to this vision served over the years as a sort of public pedagogy of struggle. As such, the Public i consistently challenged social inequalities and material injustices, while also working to strengthen the collective political consciousness within the larger community. However, this was not done solely through the publication of the newspaper, but rather through the willingness of its members to be physically present; marching against war, greed, and inequities and standing with the disenfranchised when things were at their worst.

So, when black youth were shot or incarcerated over the years, the Public i was there. When court cases required the presence of community voices, the Public i was there. When new programs to assist folks of modest means were initiated, the Public i was one of the first venues to give organizers a voice. When the struggle to eliminate the fabricated “Chief” mascot was raging at the U of I, the Public i was there. When the university sought to “quietly” install The Academy on Capitalism on the campus, the Public i was there. When hip-hop women artists from Cuba where in town, the Public i was there. When university workers rallied for a decent wage, the Public i was there. When a vigil in support of immigrant rights was held on campus, the Public i was there. When the community challenged environmental injustices in the neighborhood, the Public i was there. When a visiting theatrical production downplayed the N-word, the Pubic i was there.

In each of these instances, the paper used its pages to create public dialogue about issues that mattered. In a community climate where marginalization, systematic silencing, and brutal assaults to dissenting voices are not unusual, the Public i has been a haven where community activists, academics, and community members alike could labor, over the years, to create a legitimate political space and journalistic venue for both honest public engagement and on-going political struggle. But it has also been a venue where those who participated from different communities and various walks of life could grow and develop as writers and independent community journalists.

During my time with the Public i, I gained greater confidence in my ability to translate my ideas beyond academic journals and connect them with the folks to whom my work was most relevant. I also learned to struggle through our contradictions, in-vivo, with comrades who were committed to social change and the making of a more just world. I also learned to accept being challenged (and pushing back) as an important process for maturing our political capacity to speak across our many differences.

So, it is precisely for all these reasons that I cannot think of the Public i as simply a community newspaper. Instead, it will always exemplify for me a formidable vision and practice of struggle and dissent. A small revolutionary act of love that every Thursday nurtured our vision of a better world—a world where human dignity, freedom, and social justice are commonplace.