“I want kids to see that it wasn’t just Martin Luther King making things happen in the 1960s, it was local folks here as well. Just as it is today.”

Katie Snyder, Education Program Specialist, Museum of the Grand Prairie

The new exhibit at the Museum of the Grand Prairie in Mahomet, 1968: A Time for Every Purpose, respects the mandate of the museum to preserve artifacts that will help later generations understand the daily life of earlier residents of Champaign County—but the founder probably didn’t anticipate displaying a poster for one of John Cage’s infamous musical “happenings” in its 50th anniversary exhibit. Through these and other unexpected items, the exhibit on the cultural and political watersheds of 1968 succeeds in conveying the many ways in which the people of Champaign County both lived through and shaped the transformations of that time.

Snyder, one of the exhibit organizers and a former C-U classroom teacher, is already well known for her work as co-founder (with Shannon Percoco) of the multidimensional RESIST Art events at Urbana’s IMC in 2017 and 2018. The 1968 exhibit shares the same empowering philosophy, if in a more conventional package. Students today, she noted, still struggle with civil rights challenges, and sometimes have trouble linking the iconic names and moments they have read about (Martin Luther King Jr., lunch counter sit-ins, etc.) with their own experiences. By including portraits of local campaigns and activists, as well as an account of the local impact of King’s assassination, students can begin to understand that civil rights history wasn’t just something happening far away, but in their own community through the efforts of individuals they can emulate.

Project 500 students included future Housing Authority Commissioner and longtime Champaign County activist Terry Townsend

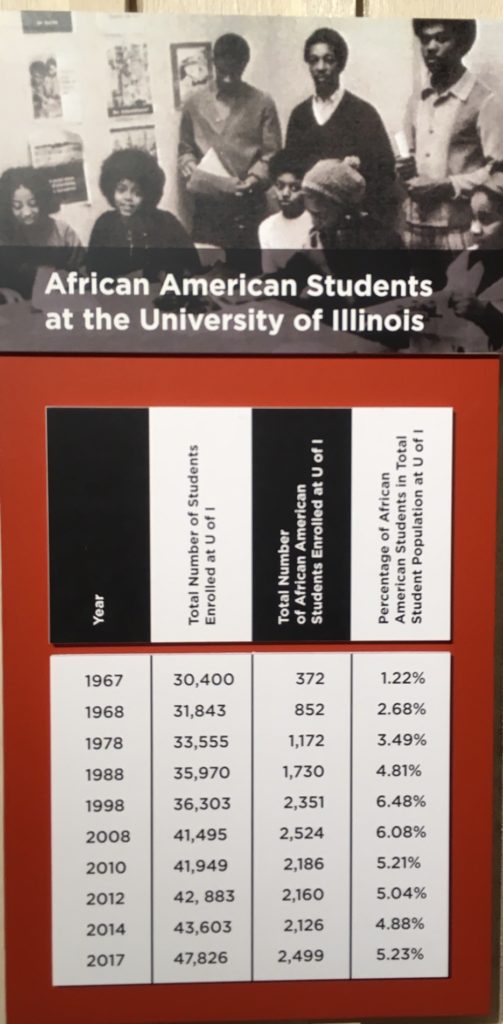

To that end the exhibit juxtaposes King and Robert Kennedy with Kenneth Stratton (the Champaign educator for whom Stratton Elementary is named) and Taylor Thomas, the first African American employed by the Urbana School District, who was hired as an Assistant Principal in 1968. Together with other members of the local chapters of the Urban League and the NAACP, the two worked to end discrimination in local housing, hiring, education and access to medical care. In the wake of King’s assassination, African American students at the university called for greater representation on campus. The result, Project 500, did boost enrollment of African American and Latino students, despite being plagued by inadequate funding and poor planning in its debut.

Antiwar protesters became increasingly common on campus

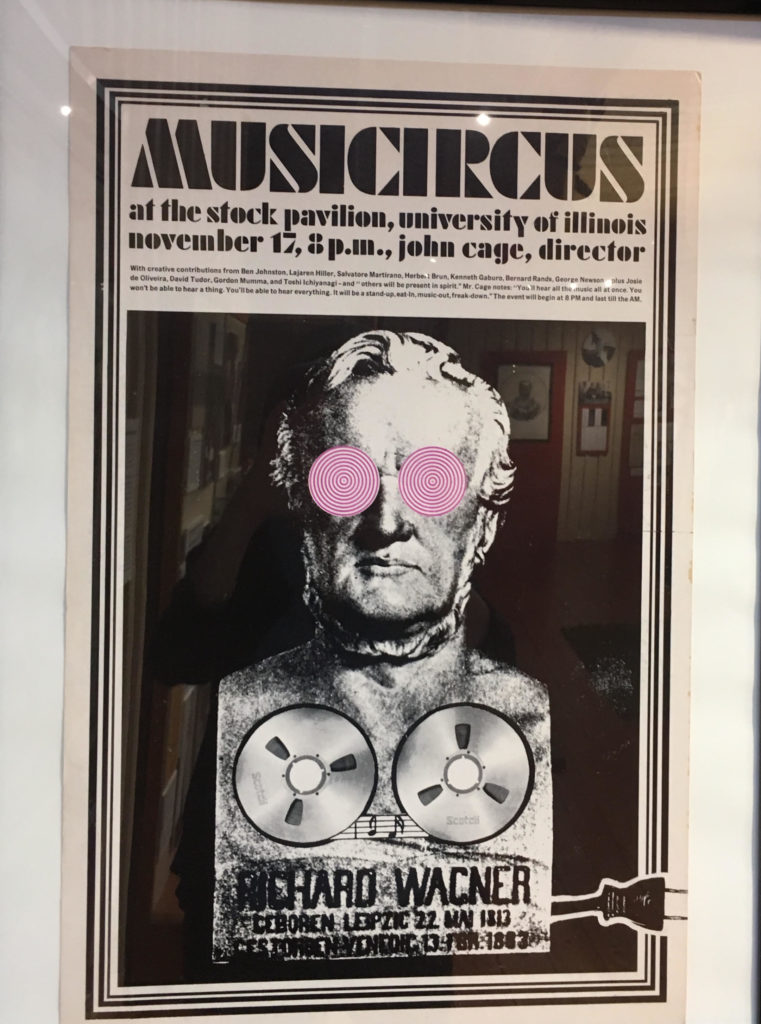

The exhibit examines other currents of 1968 as well. The counterculture experience of sensory immersion made famous by the 1969 Woodstock festival had its own local variant in the musical “happenings” organized by visiting composer John Cage. Cage was one of the pioneers of the new art form, combining performance art, spontaneous interactions, and blurred lines between performers and audience in non-traditional venues, like the University Stock Pavilion.

At one of his “happenings,” Cage projected shocking new images of the earth and the dark side of the moon from NASA, illustrating another cultural shift. The 1968 Apollo 8 mission gave humans a new perspective on the earth as a planet, and helped bring the environmental movement into the mainstream. While not every American went off to live in a commune or pick mushrooms, most Americans today have accepted the once radical ideas of recycling, carbon footprints and environmental impact studies. Seeing the earth floating alone in space communicated both the beauty and the fragility of the planet to an entire generation.

A central message of the exhibit is that the struggles of 1968 are not only local, but ongoing—which is both encouraging and discouraging. Yes, the vocabulary of the 1968 ecology movement permeates local organic markets, but the need for action to avert environmental catastrophe is even more critical today. Also sobering is that, despite fifty years of Project 500, some students are still underrepresented at the University. In 2017 the Black United Front adopted the language of 1968 in calling for a Project 1000 to increase the numbers of incoming African American and Latino students on campus and address the racial slurs that continue to pervade campus life.

Despite inadequate funding, Project 500 helped boost the number of African American students on campus

The reality of unfinished struggles and debates is perhaps what explains the tone of the most restrained section of the exhibit: that which examines the impact of Vietnam on a divided home front. In stark black and white it measures the larger human cost of the war in a few heartrending numbers: 17,000 Americans killed in 1968 alone, in company with 200,000 Vietnamese lives lost the same year. There are letters from one local soldier, the names of local casualties, and a brief commentary on the growing realization by 1968 that this was a war with no front lines and no apparent end. The parallels with the present day need little commentary.

The museum explores some of these complicated legacies in its programming. On September 15, veterans discussed the combat experience of fighting with “no front lines”; on September 30, activists with Vietnam Veterans Against the War spoke about their personal transformations and recent cooperation with veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan. And on November 4 historian Andrew Hartman of Illinois State will examine the impact of the 1960s on today’s culture wars, a topic he explored in his 2015 book, A War for the Soul of America: A History of the Culture Wars.

This is a modest exhibit. It’s limited to a temporary exhibition space (although the exhibit will be in place at least through this coming May) and is calculated to provoke reflection rather than carry out extensive education on any of the many themes it tackles, but it succeeds in reminding the viewer that 1968 was also a local experience that lives on in myriad ways. It’s an unusual view of 1968, but absolutely in the spirit of a museum dedicated to interpreting history from a local perspective.