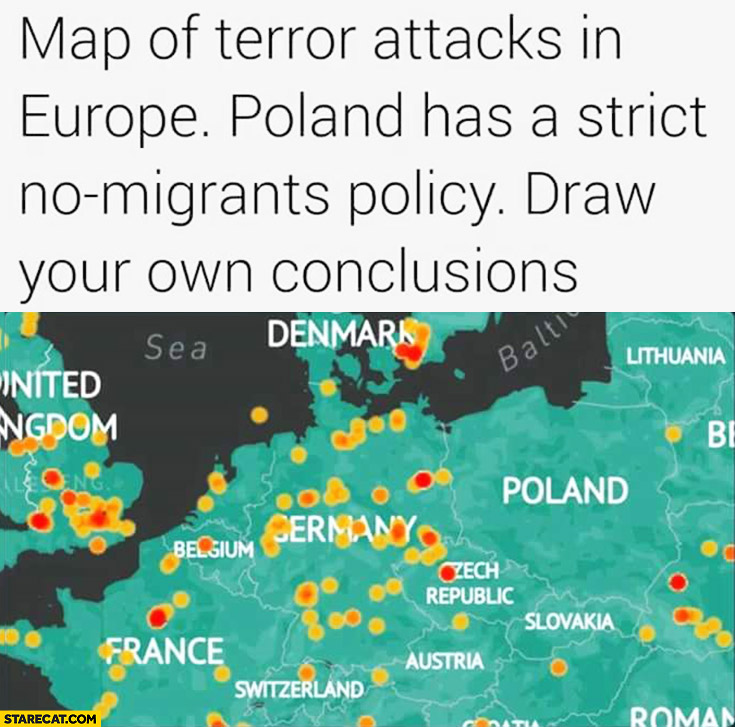

A right-wing meme circulating on the internet, that sees PiS’s anti-immigrant stance as a model

After the collapse of East European communist regimes, the watchword among Western European political elites and political scientists was “conditionality,” a term borrowed from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) lexicon to express the terms upon which the new regimes could win coveted admission to the European Union (EU) and consolidate democratic capitalism. The EU expected an economic conversion compatible with EU regulations, but added a political requirement never imposed on the current membership, “respect for and protection of minorities.” Poland and Hungary, the countries that triggered the domino transition from Communism in 1989, were on the EU membership A-list. What went wrong? Why is the new watchword “democratic backsliding”?

There are two questions here: what constitutes democratic backsliding, and what dynamics drive it? In the past decade, both Hungary (since 2010 under Viktor Orbán) and Poland (since 2015 under the government of Law and Justice (PiS by its Polish initials)) have undergone alarming shifts to an aggressive nationalist populism against fragmented and polarized oppositions. Hungary harbors a far-right party, Jobbik (whose paramilitary had to be dissolved by court order). Orban’s Fidesz Party won triple the seats in the 2018 elections of its nearest rival, the Socialists. In Poland, Jaroslaw Kaczynski’s PiS almost doubled the vote of its nearest rival, and won the country’s first single-party parliamentary majority since 1990. There is a far-right party in Poland too, but the once-mainstream PiS has soaked up much of its nationalist message and all of its limited coherence. There is no Left at the moment: the longstanding and often-governing Democratic Left Alliance was wiped out of parliament in 2015. Although both countries exhibit alarming symptoms, I will focus on nationalist populism in Poland.

The core concern about democratic backsliding in Poland is the erosion of checks and balances. The strategy of the ruling PiS party is to change the legal composition of independent commissions to allow for government-controlled partisan appointments—both for the media and for a proposed re-constituted Electoral Commission. But attacks on judicial independence have been the flashpoint. Despite EU warnings, last summer the Polish government retroactively lowered the judicial retirement age, throwing some 30% of upper-court judges into premature retirement, and opening the way for court packing. The government justification—efficiency and the removal of communist-era judges—sounded a trifle forced. In August, the EU council of judiciaries suspended its Polish affiliate, saying that its judiciary “is no longer an institution which is independent of the executive.” In October, the European Court of Justice ordered Poland’s “reform” suspended and the judges reinstated.

Last winter, the European Commission launched Article 7 proceedings for the first time against a member state, when it acted against Poland’s judicial reforms (Article 7 action against Hungary followed in September). Article 7 provides for the suspension of EU voting rights and lesser penalties for countries in breach of the 2009 Lisbon treaty’s spelling out EU fundamental values: “respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights.” The context is all the more dramatic because EU Council President Donald Tusk is the former Prime Minister of Poland and an arch-critic of the current Polish government. The Article 7 proceeding cannot succeed, however, because suspension of membership rights operates by the “unanimity minus one” rule: all other member states would have to vote against Poland or Hungary, and the two allies have each other’s backs.

Polish voters didn’t vote for PiS to curtail the courts and the news media. And the problem was not the economy as such. Poland was the only country in the EU to weather the global financial crisis without a recession. But it is now common there to talk of two Polands: (mostly) western and more urban Poland A (Euro-friendly, benefiting from the postcommunist transition) and (mostly) eastern Poland B (more rural, and more traditional in value structure). Poland A has no problem with marriage equality; Poland B does. Poland A is richer, more educated and younger than Poland B. PiS won election in 2015 by appealing above all to Poland B, to those who felt left behind by the transition, and by championing “real” Poles against the “social diseases” of lax European morals with which Poland was beset from within and without. Party leader Kaczynski called out the “powerful interests [in the rival Civic Platform Party] . . making deals with the mighty of the world.” That mighty antagonist is most frequently the European Union, and periodically and historically Russia.

Populism is not a single animal. While it can be characterized as appealing to “the people” over the heads of the elite, it obviously matters which “people.” The populist nationalism of Poland targets the Other: migrants, Muslims, Jews and West European cosmopolitans—and rival politicians as protectors of those Others. Orbán’s 2018 campaign slogan, for example, was “Hungarians first” (in unsubtle homage to his friend Trump, although Pew Global Attitudes polls show that the Hungarian and Polish publics don’t like Trump very much).

Poland today suffers from a polarizing symbolic identity politics wielded as a tool to entrench the governing party. The tangled history of Poles and Jews most recently erupted in the historical memory battles over World War II. Poles have always been sensitive about the fact that the Nazi death camps (as distinct from the more numerous labor camps) were all sited in Poland, territory that Germany governed directly during the war. To disconnect Poland from that linkage, the PiS in February 2018 criminalized any reference outside of scholarship or art to Poles “being responsible for or complicit in the Nazi crimes committed by the Third German Reich,” or to concentration camps such as Auschwitz as “Polish death camps,” unleashing a firestorm. (After Israeli intervention, a violation is now only a civil offense.) Tellingly, what was at stake here was not merely censorship but, akin to similar actions in Putin’s Russia, a reassertion of national pride and forestalling its inverse, a feeling by many in Poland B that their core identities were being insulted and humiliated.

Not incidentally, the October 2015 election that brought PiS to power occurred at the height of the refugee crisis and the disputes over an EU refugee quota allotted to Poland (a number equal to three hundredths of a percent of the population). This microscopic potential impact is clearly a large symbolic issue, and one that additionally links true Polishness with Catholic religious identity (the Polish Catholic church itself seems torn between its government and Pope Francis on this matter). The current prime minister, indeed, embraces a mission to “re-Christianize the European Union.”For the current Polish government, migrants are “rust,” a source of disease vectors, an “invasion” and above all Muslim. In a country that is 98% ethnically Polish and 91% Catholic, a Polish MP this summer explained that his government guaranteed they would not take a single Muslim migrant: “this is why Poland is so safe, this is why we have not had even one terror attack.” Opposition politicians are dodging this issue, talking instead about the Ukrainian immigrants the country has accepted and the need for refugees to fight for their rights at home.

For those who find themselves recognizing some components of this story: I had no need to strain for these parallels. Poland and Hungary are not anomalies in political dynamics, just extreme cases.

Carol Skalnik Leff specializes in East European politics in the Political Science Department at the University of Illinois. She is Vice President of the Champaign County ACLU.