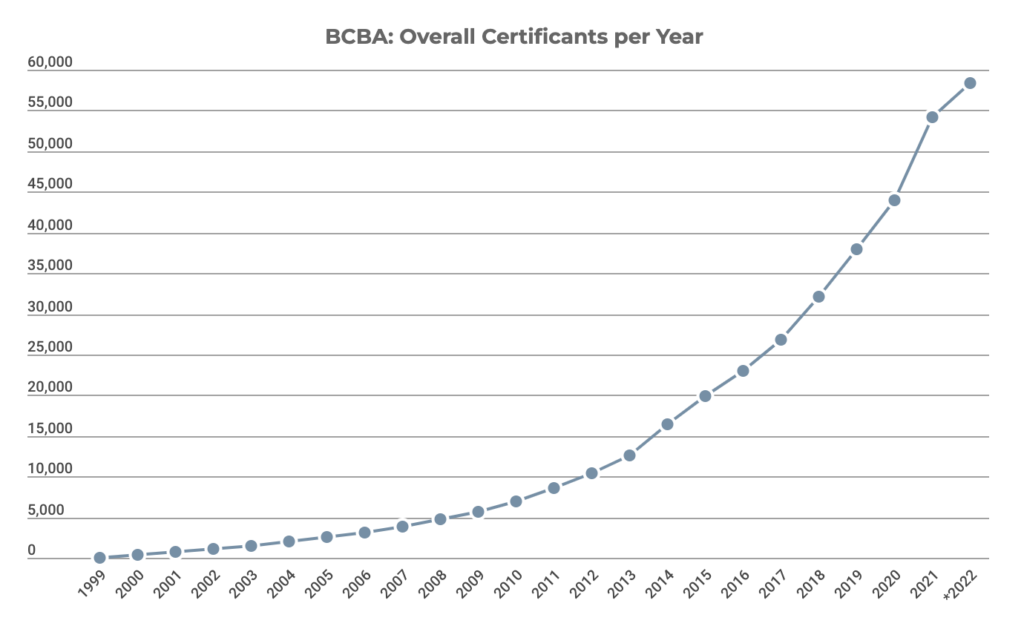

Demand for ABA practioners, including Board Certified Behavior Analysts, soared after 2014; more than 70 percent work with the autistic. From thetreetop.com/statistics/aba-therapist-demographics

Driving through north Champaign last winter I noticed a new business in a strip mall near Denny’s. At first, I assumed it was some sort of sports store due to the all-caps signage: “TOTAL SPECTRUM.” But this was not a purveyor of football helmets and jockstraps, but one of many licensed providers of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), the only state-approved “treatment” for those on the autism spectrum. As it turns out, jockstraps may be more strictly regulated than this rapidly expanding industry built upon the needs of vulnerable clients. My brief employment as an ABA “clinician” convinced me that more transparency is needed both on this industry and the therapy it markets.

Autism Speaks and the ABA Endorsement

Parents often hear about ABA through the well-known advocacy organization Autism Speaks. Their website explains ABA almost as a form of positive reinforcement: “when a behavior is followed by something that is valued (a reward), a person is more likely to repeat that behavior.” ABA proponents claim their Pavlovian approach is the only way for an autistic person to make “progress” in socialization, life skills (tying shoes, brushing teeth, etc), or academics.

Yet both ABA and Autism Speaks have critics. The Autistic Self Advocacy Network, which accuses Autism Speaks of portraying “autism and autistic people as mysterious and frightening” and thus increasing stigma, also critiques ABA. Some who underwent ABA therapy as children feel the process was not only unproductive, but actively detrimental to their overall well-being, hindering the very developmental, social, and academic skills that ABA providers claim to improve. And they are not alone. A 2020 report evaluating the use of ABA in the military dependents’ insurance system found concerns with ABA research designs and concluded that there was not “reliable evidence” of ABA effectiveness.

ABA providers often present themselves as offering innovative takes on classic ABA therapy. This is the pitch I heard. Parents and employees were told repeatedly that this center’s approach to ABA was “intuitive” and non-intrusive. The children were “allowed” to “stim” (self-stimulatory behaviors such as repetitive rocking are common ways of regulating feelings for many within the spectrum); they were not forced to make eye contact or unnecessarily restrained; and parents were encouraged to be involved in the process. Apart from illustrating the loose definition of ABA practices, these “innovations” still pursue the central premise of ABA therapy: training autistic children to do things they would prefer not to be doing.

Yet don’t we force children to do things they dislike all the time in the name of education? Almost no one argues for complete autonomy for children, but are the goals of ABA therapy really in the best interest of autistic people, or are these proposed outcomes just more comfortable for neurotypical parents and society? Or, even worse, are the clinics merely exploiting parental vulnerability for their own profit?

Coopting the Language of “Inclusivity”

In practice, ABA reduces the “autism spectrum” to a binary. Within ABA, your child has autism or they do not. Autism is an umbrella term, however, and those with autism present in many differently ways. While centers do create individual plans for each child, they also lump autistic children with wildly different needs and behaviors into the same building, and often the same room. Unfortunately, not all autistic children will thrive in the same environment, and some may even experience vulnerability. The center which employed me had toddlers in the same learning environment as preteens, presenting a potential safety issue. (I was told by a supervisor to “use my body” to prevent an older student from injuring smaller and/or younger students, even though I had not yet received CPI (Crisis Prevention Intervention) training.)

This practice of having children of wildly different ages, behaviors and need levels in the same center is often explained as evidence of a commitment to “inclusivity.” Here the language of social justice is co-opted to quell dissent from concerned employees and families. Safety and staffing concerns are not merely dismissed as incorrect, but as a moral failing. This is a powerful way to silence critics, for who wants to be against “inclusivity?” On the other hand, the “take every student and figure out safety, etc. later” approach may not simply reflect “inclusive values,” but the fact that centers are paid by insurers on a per-student basis.

Expertise on ABA is Not the Same as Expertise on Autism or Child Development

Autistic children who attend autism centers often do so in lieu of regular school. Although lesson plans are crafted by Board Certified Behavior Analysts (BCBAs), day-to-day implementation is by underpaid and overworked clinicians. Clinicians must pass a background check to work with children, but they are not teachers, health care professionals, or experts on autism, but often young people seeking to stay afloat in the gig economy. Clinicians become certified by taking a standardized test on ABA practices, but this covers basic ABA techniques, not autism, child development, or pedagogy. To be blunt, I have worked in restaurants that required menu and wine tests more thorough than the testing required of me as an ABA clinician.

Nor are there legal standards for clinic practices or staffing in most of the US. A bill was introduced in Illinois 2021 to regulate ABA licensure, but it never made it out of committee. Tragically, parents usually know little about the rudimentary training of those entrusted with the day-to-day care of their children, or the almost complete lack of regulation of ABA clinics in Illinois.

Private Equity, Public Money, and a Market Built on Vulnerability

The ABA clinic industry began to take off about ten years ago when the Affordable Care Act began to cover ABA as essential health care for diagnosed individuals under age 25. Simultaneously, many states began requiring schools to make autism services available, and the demand for autism treatment centers exploded. The growing push to provide autism services is laudable, but it also created a private equity rush into the autism clinic industry. Now most autism centers are franchises with distant owners, making oversight and investigation even more difficult. Franchise opportunities in ABA clinics advertise that, with as little as $20–35,000, you can make an “inflation-free investment” by opening a clinic. The absence of pesky state regulations in caseloads, services, staffing levels, etc. is presented as an added bonus. Health journalist Tara Barrow calls this the “fast food” approach to autism therapy.

I do not think my former coworkers or supervisors are bad people, but turning clinical care into an investment opportunity is a poor model for autism services. The profit incentive, as well as questions about ABA effectiveness, are hidden behind a veil of therapeutic expertise that is intimidating to parents. Parents of neurotypical children can choose between public, private, or charter schools. They can talk to other parents and compare school performance statistics. Such choice is obfuscated for parents of autistic children who hear from ABA “experts” that their child will only make progress with extensive ABA therapy in an autism center, before or in lieu of other schooling.

This is an industry that requires transparency and regulation. And perhaps we should start by listening to autistic adults. The fact that many autistic adults condemn ABA suggests that, at a minimum, Illinois should have more therapeutic options available to meet the varied needs of our many different autistic children.

Seth Lerner, a Champaign native and graduate of DePaul University in politics and philosophy, believes he is the foremost Talmudic scholar in his apartment building.

294 total views, 1 views today