At first glance the political crisis in Honduras seems depressingly familiar: a military coup against a left-leaning President in 2009, continued repression of opposition groups, and now a Presidential election so full of irregularities that demonstrators refuse to leave the streets. But the crisis in Honduras is much more than a reprise of past injustices; it’s a new story of globalization in all its uncomfortable contradictions: environmental and indigenous rights activists, War-on-Terror advisors, eco-tourists, miners, and tilapia farmers. This election scandal is a thoroughly 21st century event.

An “Irregular” Election Rooted in a Military Coup

The protests that have engulfed Honduras since the November 26, 2017 election really began back in 2009, when the army deposed President Manuel Zelaya. His unanticipated turn to the left had alarmed his opponents. And it was that same Left that marched on and blockaded key highways, demonstrated in public squares, and sometimes was shot at or disappeared in the months and years after the coup.

Zelaya hadn’t created this movement so much as it had created him. During the early 2000s, activists in Honduras concerned with working conditions in maquiladoras, environmental degradation, and the loss of indigenous control over collective lands began to share concerns with a worldwide network of organizations fighting similar campaigns. Social media allowed them to share strategies for forcing investor and government compliance with community demands.

The Honduran business and agrarian elite were themselves feeling the effects of a changing world. Older paths to wealth, like exporting coffee, were facing increased competition. Then, in 1998, Hurricane Mitch killed thousands, displaced more than 2 million, and destroyed 80% of crops. Mitch’s devastation led to a profound transformation of rural life and politics, as those with capital diversified into new fields such as tilapia, shrimp, palm oil, and mining ventures. Unfortunately, the regions they proposed to develop were held by communities resistant to the environmental degradation and land alienation that would result. Activist campaigns to attract international attention to the land grab also attracted Zelaya to ally himself with this new political base.

Land Grabbing in Post-Coup Honduras

The coup which removed Zelaya in 2009 moved quickly to reverse the environmental and community protections he had enacted. The moratorium on new mining concessions was lifted; aid for education, fuel costs, and food was reduced; and utility companies were privatized. Roads were carved across indigenous land, opening the way for export agriculture and mining investment.

One of the most insidious new developments was that of Charter Cities, legalized in 2011. Charter Cities were designed to spur investment by attracting foreign investment to undeveloped regions. They offered the familiar tax and trade incentives often found in Special Economic Zones, but also promised legal and regulatory incentives in the form of streamlined paperwork. Investors would be able to avoid onerous paperwork related to environmental impact statements, indigenous land tenure, labor conditions, and even the Honduran judicial and security systems. In short, investors could cease worrying about investing in Honduras because the Charter Cities would effectively be removed from Honduran government control.

While Charter Cities haven’t yet rolled out as expected, since 2009 the landscape of Honduras has become a battleground where land grabs by investors are met with community resistance. Mining, tourist enclaves, hydroelectric dams, and commercial agriculture ventures are all protected by legal structures that disenfranchise the traditional residents. Company paramilitaries abound: the Honduran NGO, Observatory of Violence, estimates there are 700 private security companies in the country. The units don’t just safeguard sites from vandalism, they also evict populations newly demoted from residents to squatters.

After the coup many activists gave up on formal politics and instead invested their energy in attracting international attention to Honduran human rights, labor, and land access issues. They opposed the 2014 U.S.-Honduran initiative to reduce gang violence, narcotics trafficking, and emigration to the U.S., in part because it relied on developing rural areas without consulting local views. Activists also publicized the danger of the plan’s reliance on the militarization of police in a country with a poor human rights record. The campaign to protect the Garifuna people of Honduras’ northern coast from the expansion of shrimp farms and eco-lodges is a good illustration of the contradictions in this era: connections with the global indigenous rights movement helped protect a local community from the global expansion of the tourist and food industries.

“A Death Trap for Environmental Activists”

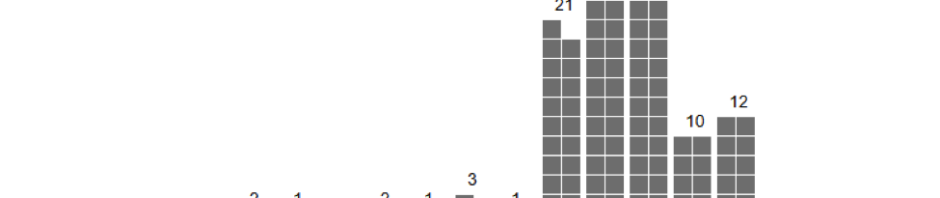

Not surprisingly, violence skyrocketed after 2009, and Honduras is now one of the deadliest countries in the world. While the government blames the violence on narcotics-linked gang violence, Human Rights Watch notes that many victims have been opposition activists or farmers who were simply inconvenient to these new land grab initiatives.

The March 2016 murder of Berta Caceres, recipient of international awards for her work opposing the construction of a hydroelectric dam in the territory of the Lenca people, was the most famous example of the lethal conditions activists face. In frustration, Amnesty International called Honduras a “death trap for environmental activists,” and Global Witness lamented that Honduras was “the most deadly place on the planet to defend the environment.”

The Surprisingly Competitive 2017 Election

The indignation following Caceres’ murder contributed to the unexpected outcome of the 2017 presidential election. The opposition candidate, Salvador Nasralla, ran on an anti-corruption platform and pledged to shut down Charter Cities and defend community land rights. Nasralla is charismatic, but expectations were low and few expected the incumbent, Juan Hernández, (a key architect of the 2009 coup) to permit a serious challenge to his reelection.

And then, on election day, Nasralla unexpectedly pulled ahead with a five-point lead. The election committee suspended the count completely for 24 hours, and after two weeks of irregular updates declared Hernández the winner with 42% of the vote to Nasralla’s 41%.

By the time the results were announced, several protesters had already been killed. The government imposed a curfew but it did little to calm the situation, and two months after the election opposition groups continue to face off against riot police in the streets. Several countries joined the OAS in calling for new elections, but the U.S. congratulated Hernández on his victory instead. The U.S. State Department had already certified on November 28th (in the midst of the election scandal) that Honduras was compliant with anti-corruption and human rights requirements, clearing the way for continued U.S. security assistance to the same units confronting the ongoing protests.

An Environmentalist Spring?

Overall, the political crisis in Honduras does sound familiar, but it’s firmly grounded in the inescapable globalizations of the 21st century. Environmental activists are using new technologies to access like-minded groups across the globe and share strategies for preserving community control against outsiders. The chaotic streets of Tegucigalpa resemble scenes from the Arab Spring for similar technology and strategy reasons. The globalization of food has made Honduran land suddenly desirable for those who would farm shrimp or tilapia for U.S. consumers, while the ease of travel allows outsiders to vacation in scuba villages that advertise proximity to exotic local culture while simultaneously dispossessing it. And the military aid that allows Hernández to keep his administration afloat? It’s a byproduct of the U.S. pursuit of security from refugees, drugs, and extremists through the militarization of far borders.

Hernández, with his ham-handed election fraud, may try to resurrect the ghost of an older oligarchical world, but his opponents are as globalized as he is now, albeit with different visions of the future. What kind of world will be built, and who will control the corners of it, is something that won’t be determined in the aftermath of one election, but it’s clearly something Hondurans are willing to fight for.